More Like Jeremy Payin-Ya

Recently, I’ve had to re-evaluate a strongly held belief. It’s an important thing for responsible adults to do every now and then; even if the opinion wasn’t wrong at the time, conditions can change. And I’m not too proud to identify such a situation now.

Here’s the old take, the one I’m revising now: Jeremy Peña is the most overrated player in baseball. At the time, it made sense. But it definitely doesn’t now.

Peña came to national attention at a portentous place in space and time. The Houston Astros had just let go of their superstar shortstop, Carlos Correa, the one-time future face of the franchise, their homegrown talisman. Peña, a 24-year-old rookie, stepped right up and filled those enormous shoes rather well, all things considered.

He played 136 games in 2022, hitting .253/.289/.426 with 22 homers. He won a Gold Glove and, more notably, was named MVP of both the ALCS and World Series. And Peña was terrific in the playoffs; he hit .345 with four home runs in 13 games. He had at least one base hit in 12 of those games, and scored a run in 10 of them.

The rookie shortstop homered for the only run of the 18-inning marathon Game 3 of the ALDS, which put the Astros through to the next round. In the final three games of the World Series, in which the Astros overhauled a 2-1 deficit on the road, Peña went 7-for-13, including a fourth-inning home run in Game 5 that put the Phillies on the back foot for good.

Forget replacing Correa; now you’ve got this lean, right-handed-hitting rookie shortstop with 20-homer power and a flair for clutch moments, playing a pivotal role on a World Series-winning team. What is that if not 1996 Derek Jeter?

That hype never seemed credible to me. Sure, he had 20-homer power, but that’s only so useful for a player with a sub-.300 OBP. And the Gold Glove-caliber defense? Well, DRS absolutely adores Peña, but other advanced defensive metrics are more lukewarm. I’ve seen plus-15-run defense at shortstop before, and it looks like Andrelton Simmons or a young Francisco Lindor; Peña seemed more pedestrian.

Over the first three full seasons of his career, Peña posted a 100 wRC+ while averaging 16 home runs and 3.0 WAR per year. That’s a good player! A valuable supplemental starter on a World Series winner, for sure. But there are a ton of really good shortstops in the league right now, some — Lindor, Corey Seager, Bobby Witt Jr., Gunnar Henderson — with truly game-breaking skill sets. A league-average hitter with some major offensive flaws, with above-average defense at best? That didn’t excite me very much by comparison.

Halfway through the 2025 season, however, Peña is leading all shortstops in WAR.

Shortstop isn’t quite as productive a position this season as it was last year; at this point in 2024, the top three shortstops in WAR were Henderson, Witt, and Mookie Betts, and all three are having somewhat disappointing campaigns in 2025. But Peña isn’t just beating out scrubs here. Witt, Trea Turner, and Jacob Wilson are all on pace for more than 6.0 WAR; Wilson is almost hitting .350, for God’s sake.

Elly De La Cruz has 18 home runs and 21 stolen bases, which puts him on track to become just the seventh shortstop ever to post a 30-30 season. And he’s not too far from being on pace for 40-40, a feat achieved by only one shortstop ever: Alex Rodriguez.

But Peña, whom I’d once dismissed as hitting for an empty average, is now toting around a .325/.380/.495 batting line and a 150 wRC+, which leads all qualified shortstops in 2025. His 4.0 WAR, having played in all 81 of Houston’s games this year, is “in the MVP discussion” territory at the very least. Whatever I thought about Peña before, I don’t think it’s possible to overrate a player who’s produced the way he has so far this season.

It seems that Peña himself has chosen this moment to reconsider his place in the league-wide pecking order. He and the Astros are (or were) in negotiations for a contract extension that would’ve bought out his final two arbitration years, plus three seasons of free agency. Five total, at a little north of $20 million per.

Just this week, however, Peña switched agents, from Beverly Hills Sports Council to the dreaded Scott Boras. Which doesn’t mean Peña won’t sign an extension — Boras seems to get along well with Houston, having locked Jose Altuve and Lance McCullers Jr. into long-term extensions there — but it does indicate Peña is seeking top dollar for his services.

What should Peña be asking for? Well, as a college player who didn’t debut until he was 24, Peña got a little bit of a late start on the march toward free agency, but he’s also been a starter since Opening Day of his rookie year, which makes his service time calculation quite easy.

If Peña doesn’t sign an extension, he’ll hit free agency heading into his age-30 season. He’ll be two years older than Seager, one year older than Dansby Swanson, and the same age as Turner when they were free agents. Mostly, that means he won’t be in line for the kind of ludicrously long-term contracts Juan Soto and Bryce Harper got.

But if he’s this productive at the end of his 20s, big money is still very much a possibility. If I had to choose, I’d have this version of Peña over Swanson in his walk year, and the latter still got a seven-year contract as the fourth-best shortstop in his class. For that matter, I could see Peña going into free agency as Turner with better defense but worse baserunning. He’d need to keep hitting like this for more than three months, but it’s a much more realistic possibility than it was this time last year.

The sky is the limit. The big question now is whether Peña, a true talent 100 wRC+ guy for three years, is now a true-talent 150 wRC+ guy.

Probably not. Peña has unquestionably made massive improvements at the plate over the course of his major league career. Just off the top of my head, he’s cut his strikeout rate from 24.2% as a rookie to 17.1% last year and 16.0% this year — that’s a reduction of more than a third. And for a hitter who doesn’t walk and doesn’t have top-end power, not striking out is a major plus.

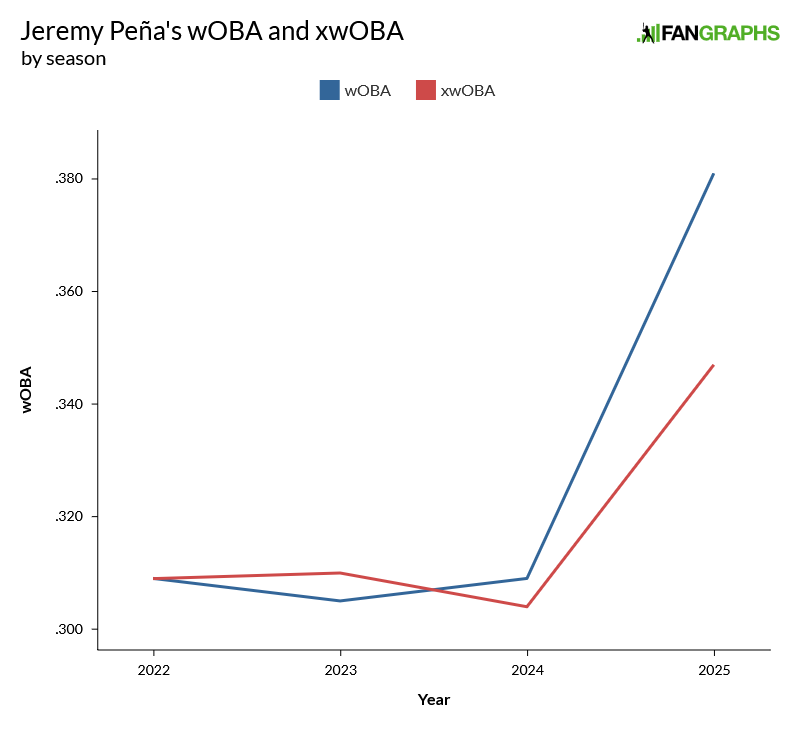

But while Peña’s improvements are real and meaningful, I do think they’re somewhat overstated by the top-line numbers. In the olden days, we’d talk about his .364 BABIP, but I find this graph of his wOBA (.381) versus his xwOBA (.347) to be most illuminating.

A wOBA in the high .340s is still great, especially for a shortstop, but it’s not what’s showing up in the box score right now. José Ramírez has a .379 wOBA right now; once you get down around .350 you’re looking at Zach Neto.

And Peña isn’t making particularly harder contact. He’s not putting the ball in the air more — in fact, his groundball/line drive/fly ball ratios are eerily similar to what they were last year.

| Season | GB/FB | LD% | GB% | FB% | Bat Speed | Contact% | HardHit% | Barrel% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 1.57 | 19.2% | 49.4% | 31.5% | 72.6 mph | 77.1% | 38.8% | 5.4% |

| 2025 | 1.58 | 19.8% | 49.0% | 31.1% | 72.4 mph | 75.9% | 41.3% | 7.7% |

Just looking at the numbers, it seems like Peña has made a number of marginal gains — a few more walks here, a little more selectivity within the strike zone there — that have combined to pay off big.

Plus, there’s one big one: The fabled in-air pull rate. Last year, 15.2% of Peña’s batted balls were in the air and to the pull side; this year, that percentage is up to 20.1%.

The implications of that change are staggering for a right-handed hitter who plays his home games in Daikin Park. The Crawford Boxes are so close to home plate Peña can probably see the pores of the fans sitting in the left field seats.

So far this year, Peña has hit 48 balls 300 feet or more. Of those, 22 have been to the pull side, including 16 out of Peña’s 20 base hits on balls of that distance, and all 11 of his home runs.

If you’re worried about the discrepancy between Peña’s wOBA and his xwOBA, this is a pretty powerful counterargument for two reasons. First, xwOBA accounts for launch angle and exit velo, but not batted ball direction. So a hitter who puts his fly balls into a particularly profitable area of the field, as Peña does, ought to naturally outperform his expected stats to some degree.

Second, there’s a very clear explanation for how Peña is doing this. And believe it or not, it comes from a place that’s so narratively fitting you almost couldn’t make it up.

Last year, Peña came to the plate with his feet square and his bat wobbling between one and two o’clock. His leg kick naturally brought his front foot closer to the plate, resulting in his momentum going toward right center.

You want Jeter? This swing is Jeter as all get-out. Any more Jeter and it’d come with a gift basket.

But it’s also kind of like stepping in the bucket. It’s the bucket in the left-handed batter’s box, but still, Peña’s momentum was not going straight back toward the pitcher.

This year, instead of trying to correct his stride, Peña is just starting with his bat on his shoulder, his stance open, and his feet farther apart.

It looks to me like he’s keeping his weight back longer as well, but what’s indisputable is that he’s now striding directly toward the pitcher. That means he can pull the ball without fighting his body weight, and allows him to take greater advantage of that great architectural gift out in left field.

Now here’s the fun part, from a feature in The Athletic this week by Chandler Rome. Peña landed on the new stance over the winter, during a session with his new workout buddy: Carlos Correa. How cool is that?

It took a couple years, and some tinkering, but Peña is now indisputably the kind of player he was thought to be as a rookie. He’s been the best position player by a mile on the team with the second-best record in the AL. He’s going to be an All-Star, and barring a massive second-half regression he ought to vacuum up down-ballot MVP votes. The hype, if anything, was not big enough.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

The first thing I thought of when this got into his increase in pulling the ball into the Crawford Boxes was maybe Isaac Paredes had some effect on him.

I guess that could be true to some extent, but, it’s funny that the guy he replaced was the one that helped him pull off the change.