Move Over, Wrigley: Steinbrenner Field Has the Majors’ Wildest Wind

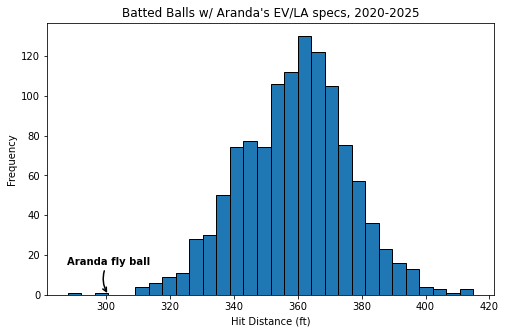

I thought I had it sorted out; it took one batted ball to convince me otherwise. It was the bottom of the seventh inning during the Rays’ first game in their new George M. Steinbrenner (GMS) Field digs. Jonathan Aranda worked his way into a 2-0 count against Rockies reliever Tyler Kinley. With runners on second and third, one out, and the Rays down two runs, Kinley hung a slider. Aranda uncorked his A swing, launching the ball deep to right field. Off the bat, I thought it looked way gone. It didn’t even go 300 feet:

Aranda’s fly ball left the bat at 99 mph with a 37 degree launch angle. Since 2020, there have been 1,173 balls hit with exit velocities between 98 and 100 mph and launch angles between 36 and 38 degrees. Only one traveled a shorter distance than Aranda’s:

When I ran my projections on the expected GMS Field park factors last Friday, I mostly focused on air density, given its strong relationship to run-scoring conditions. I relegated wind considerations to the “future analysis” section, implying its impact was mostly peripheral. I was wrong. GMS Field might surpass Wrigley Field as the park most affected by its wind conditions on a game-to-game basis.

As Mike Petriello wrote in February, Wrigley had by far the most “wind-affected balls” over the previous two seasons, with conditions pushing 250 batted balls at least 25 feet. (Fenway Park came in second, with around 75 batted balls.) The most wind-affected non-home run of the last two seasons was an Enrique Hernández fly ball, which was knocked down 82 feet. Aranda’s fly ball from Thursday traveled 60 feet short of the average for that exit velocity/launch angle combination; if all of that was wind effects, it would’ve ranked third among the wind-affected non-home runs in Petriello’s rankings.

Now, it’s possible Aranda hit the ball with a ton of topspin, though based on the arc of the ball, I’m skeptical. But the conditions were exactly right for this sort of outcome. Aranda made contact with the pitch right around 6 PM Eastern that Friday. According to hourly data provided by NOAA’s Integrated Surface Database, the wind was blowing directly in from right field at 24 mph.

Strong winds, it turns out, are a typical part of the GMS Field experience. (That’s less the case at Sutter Health Park in Sacramento, which I also wrote about last week.) I looked at wind data from equivalent game times from the Tampa International Airport data station, which is adjacent to GMS Field, during the 2024 season. The average wind speed was just over 12 mph, which would’ve ranked as the windiest fully outdoor stadium in baseball according to the late David Kagan’s 2015 rankings for The Hardball Times. (Wrigley ranked in the middle of the pack but, as Kagan also wrote in 2015, the standard deviation of wind conditions is high for both speed and direction.)

But looking merely at the strength of the wind understates its potential impact, as Rays’ president Matt Silverman expressed during a mid-broadcast interview in the home opener. “When you don’t have that second deck, you don’t have as much protection from the wind,” Silverman said. “So it has a little bit more of an exaggerated effect than normal major league ballparks.”

As Silverman said, the absence of obstacles around the stadium enhances the wind effects. GMS Field is not a large ballpark. There are no seats in the outfield. Behind the short right field fence, there are rows and rows of parking. There are no skyscrapers in sight, no skyline to block the full flow of the wind.

Clay Nunnally, a scientist at MLB, authored an article in March of 2023 that illustrated the way that wind operates at most stadiums. “Wind at a ballpark has to negotiate large structures that surround the field,” Nunnally wrote. “The height (X) and range (Y) of the wind shadow are roughly on the order of magnitude of the height of the barrier. In practice, that means, especially for large ballparks, the wind that affects ball trajectories doesn’t necessarily match the prevailing wind conditions.” GMS Field operates in significantly different conditions.

So will the wind help the pitchers or the hitters? As with Wrigley, the answer is a hearty “it depends.”

“One of the big questions is the wind,” Silverman said in that same interview when asked about the GMS Field park factor expectations. “We know how the ballpark plays in terms of dimensions, but how are the winds going to change? They’re different during the afternoon than they are in the evening, they’re different today than they’re going to be a couple months from now. So that’s going to be one of the big wild cards.”

I set out to answer Silverman’s (rhetorical) question. But first, I needed to know how GMS Field was oriented in space.

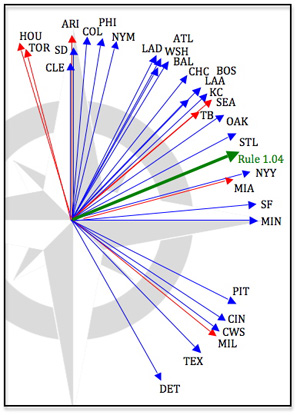

MLB Rule 1.04 stipulates that “it is desirable that the line from home base through the pitchers plate to second base shall run East-Northeast.” In his 2014 article “Lost in the Sun: The Physics of Ballpark Orientation,” Kagan outlined a method for extracting the orientation of a ballpark using Google Maps coordinates. From that piece:

GMS Field slots in right between Oakland and St. Louis on Kagan’s graphic above, oriented at a 60 degrees east-northeast angle. A wind direction of 60 degrees, then, means the wind blows directly in from center field; 15 degrees would blow directly in from behind the left-field foul pole, and 105 degrees from behind the right field foul pole.

Because GMS Field sits just east of Tampa Bay, the wind — in theory — should blow out in the afternoon, favoring hitters, and gradually shift as the day proceeds.

“The land should heat up faster than Tampa Bay during the day; that means lower pressure will develop over land so the wind will blow towards the lower pressure, or towards the east,” Annie Rosen, a PhD student in atmospheric sciences at UCLA (and also my sister), told me. “At night, this process reverses — the ocean can hold more heat than the land, and so the wind will blow from the land to the bay or towards the west.”

To see if practice affirmed this theoretical relationship, I pulled hourly weather data from Tampa International Airport from the last 10 years, then bucketed each hour by whether the wind was blowing out, in, or neither. “Blowing in” was defined by the parameters outlined above with a little buffer on each side, so any wind direction between 0 and 120 degrees; “blowing out” was defined as the winds moving directly opposite these winds, or any wind direction between 180 and 300 degrees. Everything in between I labeled a crosswind.

The data backed up the theory. In the afternoon, the wind almost always blows out, favoring the hitters. As the day proceeds, the park becomes more pitcher-friendly:

| Time | Wind Blowing IN | Wind Blowing OUT | Crosswind |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PM | 19% | 63% | 18% |

| 2 PM | 17% | 67% | 15% |

| 3 PM | 16% | 68% | 15% |

| 4 PM | 18% | 67% | 15% |

| 5 PM | 19% | 63% | 18% |

| 6 PM | 22% | 57% | 22% |

| 7 PM | 24% | 48% | 28% |

| 8 PM | 29% | 36% | 35% |

| 9 PM | 32% | 27% | 41% |

| 10 PM | 37% | 24% | 39% |

| 11 PM | 44% | 21% | 36% |

The time of year also shifts the wind patterns, a relevant concern given the quirks of the Rays’ schedule. To avoid the summer rains in South Florida, the Rays will play most of their home games at the start of the season. Nineteen of their first 22 games, and 37 of their first 54, will be played at GMS Field. They play just eight home games in both July and August. The early season conditions, therefore, will have a disproportionate impact on the Steinbrenner Field park factor.

Below, I’ve split out the frequency of wind conditions by month and time period. In April, the wind is very likely to blow out in the afternoon (64% of the time over my 10-year sample), while it’s more of a mixed bag in the evenings, blowing out 42% of the time and blowing in 23% of the time. But as the fall comes around, those frequencies change. By September — and potentially even October — the park will start to play much more like a pitcher’s park:

| Month | Time Period | Wind Blowing IN | Wind Blowing OUT | Crosswind |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April | Afternoon | 19% | 64% | 17% |

| Evening | 23% | 42% | 35% | |

| May | Afternoon | 19% | 66% | 15% |

| Evening | 29% | 33% | 38% | |

| June | Afternoon | 15% | 71% | 15% |

| Evening | 27% | 40% | 33% | |

| July | Afternoon | 8% | 79% | 13% |

| Evening | 25% | 38% | 37% | |

| August | Afternoon | 16% | 65% | 18% |

| Evening | 34% | 33% | 34% | |

| September | Afternoon | 28% | 54% | 17% |

| Evening | 45% | 17% | 38% | |

| October | Afternoon | 49% | 31% | 20% |

| Evening | 55% | 12% | 33% |

It all feels early to say, but then again, there are decades of weather data, and the park isn’t going to change its orientation anytime soon. At Wrigley, there’s a difference of 150 points of OPS between strong winds out and strong winds in, according to Matt Trueblood’s findings. If I had to guess, GMS Field will play even more extreme, blowing baseballs every which way around the high Tampa sky.

Michael Rosen is a transportation researcher and the author of pitchplots.substack.com. He can be found on Twitter at @bymichaelrosen.

I’ve been watching Florida State League games since 1969 and can tell you weather plays a major factor, and not just because of the evening thunderstorms. Before the sultry summer pattern takes hold, fly balls in an ever-shifting wind, particularly unexpected gusts, can be an adventure. A lot of FSL parks play way more pitcher-friendly in the summer than they do in spring training, for reasons outlined by the meteorologist cited. It’ll be interesting to see if the Rays benefit from playing outside.