Nathan Eovaldi Is Making Delicious Lemonade

If motor preferences were the final word on pitcher performance, Nathan Eovaldi would be sitting on a beach somewhere.

Eovaldi throws from a low slot, releasing his pitches from an average arm angle of 30 degrees. (Zero degrees is fully sidearm; 90 degrees is straight over the top.) Many low-slot pitchers have a supination bias. There are downsides to being a supinator — their preference for cutting the baseball tends to produce crummy four-seam fastballs — but they usually have no trouble throwing hard breaking balls; they can also more easily harness seam-shifted wake to throw sinkers, sweepers, or kick-changes. Low-slot supinators, like Seth Lugo, can basically throw every pitch in the book. High-slot pronators like Ryan Pepiot or Lucas Giolito don’t have that sort of range, but make up for it with excellent changeups and high-carry fastballs.

Eovaldi is, tragically, a low-slot pronator. Not many low-slot pronators make it to the big leagues. The pronation bias blunts their ability to throw hard glove-side breakers, and the low arm angle obviates the pronator’s nominal advantage, killing the carry on their fastball. As Tyler Zombro of Tread Athletics (now a special assistant of pitching for the Cubs) said in his primer video on motor preferences, “I know in stuff models and just off of Trackman alone, this arsenal with this slot is not that attractive.”

As Zombro goes on to say, low-slot pronators can work around their limitations by using angles. The video uses B-roll of guys like Chris Sale, Nick Lodolo, and Tayler Scott to show that extreme horizontal release points can augment an otherwise uninspiring arsenal. Eovaldi doesn’t belong to this class of pitcher. He releases the ball from about 2.5 feet to the right of the center of the rubber, nowhere near the extremes of those three pitchers. And while his vertical release point is low — just 5.3 feet off the ground on average — the measly 12 inches of induced vertical break on his heater means that the vertical approach angle is more good than great.

Velocity has a way of erasing shape concerns. But Eovaldi is no longer the flamethrower of his youth. Once capable of dialing up triple digits, Eovaldi’s average fastball is all the way down to 93.9 mph, dropping a tick and a half from 2024 to 2025.

And yet — somehow — he is among the frontrunners for the American League Cy Young. By both results and peripherals, Eovaldi is dominating, running a 1.78 ERA and a 2.13 FIP through nine starts. His 28.6% strikeout rate is the highest of his career, his 2.4% walk rate the lowest. In his age-35 season, Eovaldi is uncorking a career year.

Now a wily veteran, Eovaldi is making the most of what he’s got. Sure, he can’t throw a breaking ball without sacrificing significant velocity. But there’s one pitch where the lack of spin talent is actually an asset: The splitter, which hardly spins at all. In 2025, Eovaldi belongs to the exclusive club of split-first starting pitchers.

Eovaldi wasn’t always so split-happy. As recently as 2021, the splitter was his fourth-most-used pitch, relegated mostly to late-count duty against lefties. Eovaldi sat 97 on the heater then, even running it up to triple digits when he really needed it. The arm speed of his prime years allowed his slider to play despite its so-so shape, giving him a strong out pitch against right-handed hitters.

As velocity loss set in, Eovaldi was forced to adapt. At 97 mph, the fastball shape wasn’t as much of a concern; at 94, it’s a problem. His slider was workable at 86 mph; it isn’t viable at 84 mph. So Eovaldi’s essentially abandoned it, throwing just 12 sliders total so far this season. Enter the splitter.

Nine starts into his 2025 campaign, Eovaldi is throwing his splitter 29% of the time. It’s no longer a niche pitch to break out in late counts against opposite-handed hitters; Eovaldi is throwing the splitter to everyone in basically every count. That works for him on two levels. First, it’s a great pitch by the specs. At 87 mph and nearly an inch of (non-gravity-induced) drop, that shape has an enviable combination of speed and depth. The generous usage also points to another element of Eovaldi’s success — his ability to be a pitch type random number generator.

To quantify this random number generator skill, I calculated something called the Shannon entropy for pitch types thrown in early counts. If the probability of something happening is x, the Shannon entropy is basically 1/x, or the inverse of probability. (The math is a little more complicated than that, as this excellent explainer video gets into. Conceptually, it’s close enough.) If Eovaldi were to throw only fastballs in early counts, his Shannon entropy would equal one. Anything above that figure points at more randomness in the pitch selection.

When I wrote about Spencer Schwellenbach earlier this year, I noted his tendency to throw any pitch in any count. Schwellenbach throws six pitches, which helps. By the entropy rankings, most of these many-pitched fellows top the list of highest pitch type entropy in early counts. (Lugo, no surprise, sits at the top.)

| Player | Average Entropy |

|---|---|

| Seth Lugo | 2.65 |

| Michael Lorenzen | 2.34 |

| Paul Skenes | 2.20 |

| Luis Severino | 2.19 |

| Nick Martinez | 2.19 |

| Spencer Schwellenbach | 2.18 |

| Sonny Gray | 2.17 |

| Matthew Liberatore | 2.17 |

| Max Fried | 2.17 |

| Cal Quantrill | 2.16 |

| Sandy Alcantara | 2.13 |

But among pitchers with just four pitches in their arsenal, Eovaldi is a stand out, posting one of the highest entropy scores for anyone in his cohort. To hitters from both sides of the plate, Eovaldi will drop any pitch in any count:

| Pitch Type | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Curveball | 33.0 |

| Four-Seam Fastball | 31.1 |

| Cutter | 19.4 |

| Splitter | 16.5 |

| Pitch Type | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Four-Seam Fastball | 25.0 |

| Splitter | 25.0 |

| Curveball | 21.8 |

| Cutter | 18.8 |

| Slider | 9.4 |

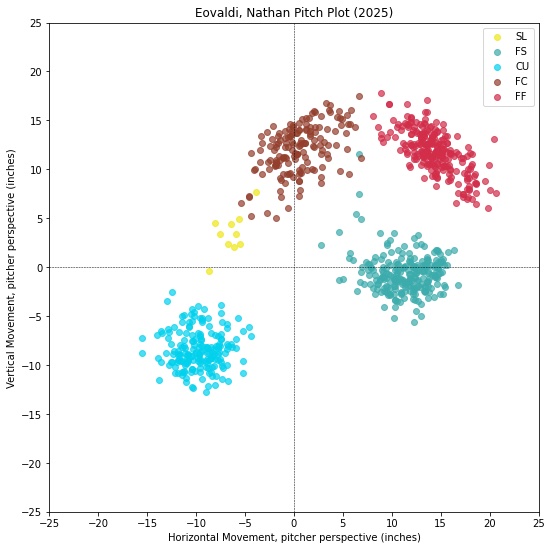

In addition to the four-seam fastball and the splitter, Eovaldi throws a curveball and a cutter; the movement profiles of both are informed by his pronation tendencies. Because Eovaldi can’t really spin the ball, the cutter actually averages a half-inch of arm-side movement, but it works as an effective bridge pitch, filling out the middle of his pitch plot. In order to throw a breaking ball, he must sacrifice significant velocity, which explains the shape and speed of his curveball, a huge looper averaging 76 mph:

These four pitches produce the pitch plot seen above. Even though it’s just four pitches, a pittance by modern standards, he still stands out in Baseball Prospectus’ arsenal metrics, ranking in the 88th percentile by movement spread and 93rd percentile by velocity spread. As Stephen Sutton-Brown found when creating these metrics, wide spreads in movement and velocity in a pitcher’s arsenal mess with hitter timing, helping pitchers like Eovaldi perform above the quality of their stuff.

Armed with a nasty splitter, a diverse arsenal, and the ability to throw all pitches in all contexts, Eovaldi ties it together with sublime command. His walk rate is elite, currently the lowest among all qualified starters. He locates nearly every splitter either at the bottom of the zone for a strike or just below for chase. His curveball lives right off the outer edge. He zones his fastball over 60% of the time, ranking in the top quartile of pitchers with at least 100 fastballs thrown, per Alex Chamberlain’s Pitch Leaderboards.

Compared to his peers at the top of the WAR leaderboards — Hunter Brown and Tarik Skubal, to name a couple — Eovaldi is lacking in flash. There’s almost certainly regression coming, particularly in his home run rate, given how much he’s living around the zone with mediocre stuff. But it must be admired how Eovaldi is extracting the most from his skill set. Can’t spin the ball? Make the splitter your primary pitch. Lack velocity? Turn that into a strength. Crummy fastball? Hide it. Given a pair of lumpy lemons, Eovaldi is turning them into a delicious lemonade.

Michael Rosen is a transportation researcher and the author of pitchplots.substack.com. He can be found on Twitter at @bymichaelrosen.

That entropy table has a lot of players that went through the Reds and Padres, wonder if this is part of their strategy for coaching pitchers