Shane Smith Is a Gleaming Beacon of Hope in a Land of Sorrow

If White Sox fans hadn’t already been inured to calamity by now, surely the ending of Tuesday afternoon’s game would’ve sent them into an incoherent, frothing rage. Having made it to the bottom of the ninth inning in Cleveland tied 0-0, Mike Clevinger took the mound. Clevinger, for reasons I do not remotely understand, is Chicago’s closer, and the inning before he’d come in to retire José Ramírez with two outs and the bases empty to preserve the tie.

Clevinger started the inning by allowing an infield single to Carlos Santana, alerting the world to the hitherto unknown fact that Santana can still run at this phase of his career. Then, the once-coveted workhorse walked three straight Guardians on a combined 21 pitches to force in the winning run. By the end of his stint, Clevinger’s fastball velocity was dipping into the 91 mph range. It was the second time in the first 10 games of the season that Clevinger took the decision in a 1-0 defeat, and Chicago’s second walk-off loss in as many games.

A game like this invites many questions, most of them more easily answered by the works of Nietzsche or C.S. Lewis (depending on your philosophical predilections) than baseball analysis. But there is good news, other than the fact that we’re all going to die one day, and when we do, we won’t have to watch the White Sox anymore.

See, Shane Smith was nails. Again.

Never heard of Shane Smith? I don’t blame you. I was in the room when the White Sox plucked him from the Brewers in the Rule 5 draft last December, and I’d all but forgotten about him by the time he made Chicago’s opening rotation. When I saw his name on the schedule, I thought: “Shane Smith, the jackass who cofounded Vice News? No, the other jackass who cofounded Vice News.”

Much to his own detriment in terms of SEO, this Shane Smith is a pitcher, and one with a fairly unusual career path: A monument to odd timing.

Smith went to Wake Forest, which was not quite the pitching factory it’s become, but it was still a good program, and head coach Tom Walter had coached Smith’s father at George Washington in a previous life. Smith sat out all of his first year on campus, 2019, with an injury, and won the closer’s role as a redshirt freshman. He went 2-0 with a save and nine strikeouts against a single hit… and then COVID hit after he’d thrown just five innings.

The next year, Smith moved to the rotation, where he lasted just two starts before he tore his UCL, truncating his entire college career to just 10 1/3 innings. A draft-eligible sophomore, he moved on to professional baseball, where the Brewers signed him as an undrafted free agent. Back when the draft was 40 or 50 rounds, or lasted until everyone passed, it was borderline-impossible for a UDFA to reach the majors. It’s more common now, with a 20-round draft, but not by much.

Still, once his elbow healed, Smith carved up the low minors as a one-inning reliever, and in 2024 the Brewers tried him out as a starter, where he tinkered with his repertoire but suffered a slight drop in fastball velocity.

And just like that, it was his fourth offseason as a pro, so the Brewers had to either add him to the 40-man roster or leave him unprotected in the Rule 5 draft. Counting college, the minors, the Arizona Fall League, and a season of summer ball in the Coastal Plains League, Smith had thrown only 184 1/3 competitive innings since graduating from high school, and Milwaukee couldn’t find a spot for him.

Despite his inexperience, Smith pretty obviously had big league-quality velocity and a big league-quality curveball. That alone, plus his gaudy minor league strikeout numbers (203 in 157 innings across all levels) made him one of the better prospects available in the draft, and nobody batted an eye when the White Sox took him with the first selection.

Given Chicago’s paucity of quality pitching and low team expectations, it seemed like Smith had a good shot not only to break camp with the White Sox, but also to survive on the major league roster all year. But as a reliever. That’s where he’d been most effective, and that’s what Eric Longenhagen wrote him up as at the time of the Rule 5 draft.

The conceit of the Rule 5 draft is that it offers big league opportunities to players who would otherwise be buried in the minor leagues. In practice, most Rule 5 draftees — if not all — are not completely ready for that opportunity when they get it. Most get returned. The pitchers who do stick around all year tend to do so in the bullpen, where they can get by on max effort and their two best pitches, while their manager shields them from high-leverage situations. A few of those guys make it through every season.

But for a Rule 5 pick to survive an entire season as a starter? Well, it happens even less often than an undrafted free agent makes the majors. Last year, the A’s had Mitch Spence in middle relief for the first six weeks of the season, before moving him to the rotation in mid-May.

Spence was OK. He made it into the fifth inning 21 times out of 24 starts, and through the fifth inning 17 times. As a starter, he posted a 4.64 ERA and a 4.37 FIP, and opponents hit .284/.338/.471 off him. That didn’t land Spence on anyone’s Rookie of the Year ballot, but for a rookie without big strikeout numbers, pitching in front of a 93-loss team? It’s hardly embarrassing.

But before Spence, you have to go all the way back to Brad Keller’s monster rookie season in 2018 to find a Rule 5 pick who thrived as a starter in his first major league campaign. And both Spence and Keller started in the bullpen and worked their way into the rotation over time. Smith got dropped straight into the deep end.

You’d never know it by watching him.

In his first start, Smith walked four but allowed only two hits and two runs over 5 2/3 innings. He was even better on Tuesday, striking out six and allowing two hits and a walk over six scoreless innings. Smith has now put together consecutive starts of two or fewer hits, two or fewer runs, and at least 17 outs.

That might not sound like much, but it’s a pretty rare achievement. It’s only the fifth instance of a White Sox pitcher hitting those marks in consecutive starts this decade; it’s only happened 13 times total since the strike and 18 times since 1901. Garrett Crochet never did it, nor did Lance Lynn or Jose Quintana or Jack McDowell or Early Wynn. Mark Buehrle never did it, even when he set a record for consecutive batters retired. Chris Sale only did it twice. If Smith comes out and hits his marks again on Sunday, when he’s scheduled to oppose Crochet of all people, it will be the first streak of three games meeting those criteria in all of franchise history.

As thrilling of a development as this is, I’m inclined to be somewhat conservative in my enthusiasm. Mostly because it’s a two-start sample at the beginning of the season, and as a matter of general principle I don’t believe anything in a baseball season is real until Memorial Day. Nobody ever went broke betting on Chris Shelton to regress to the mean.

Nestled into the small-sample caveat is the fact that Smith has not faced especially strong competition. The Twins are so lost they risk running afoul of the Hare Krishna joke from The Muppet Movie. And the Guardians had scored just 34 runs in nine games before they had the misfortune of encountering the unhittable Smith.

It’s also too early to draw sweeping conclusions about various pitches’ effectiveness. Smith hasn’t thrown any of his pitches more than 66 times, and what could look like a major uptick in whiff rate might just be one hitter coming up to the plate with a wonky contact lens.

I will say two things in his favor: First, the fastball velocity is not overpowering, but it’s solid. Smith is averaging 94.6 mph on his four-seamer, and hitting 97. He’s losing some velocity his second time through the order, but when he struck out Kyle Manzardo to close out the bottom of the sixth on Tuesday, that marked the furthest Smith had pitched into a start since high school at least. He’s a big guy; I’m willing to be patient as he builds up some stamina.

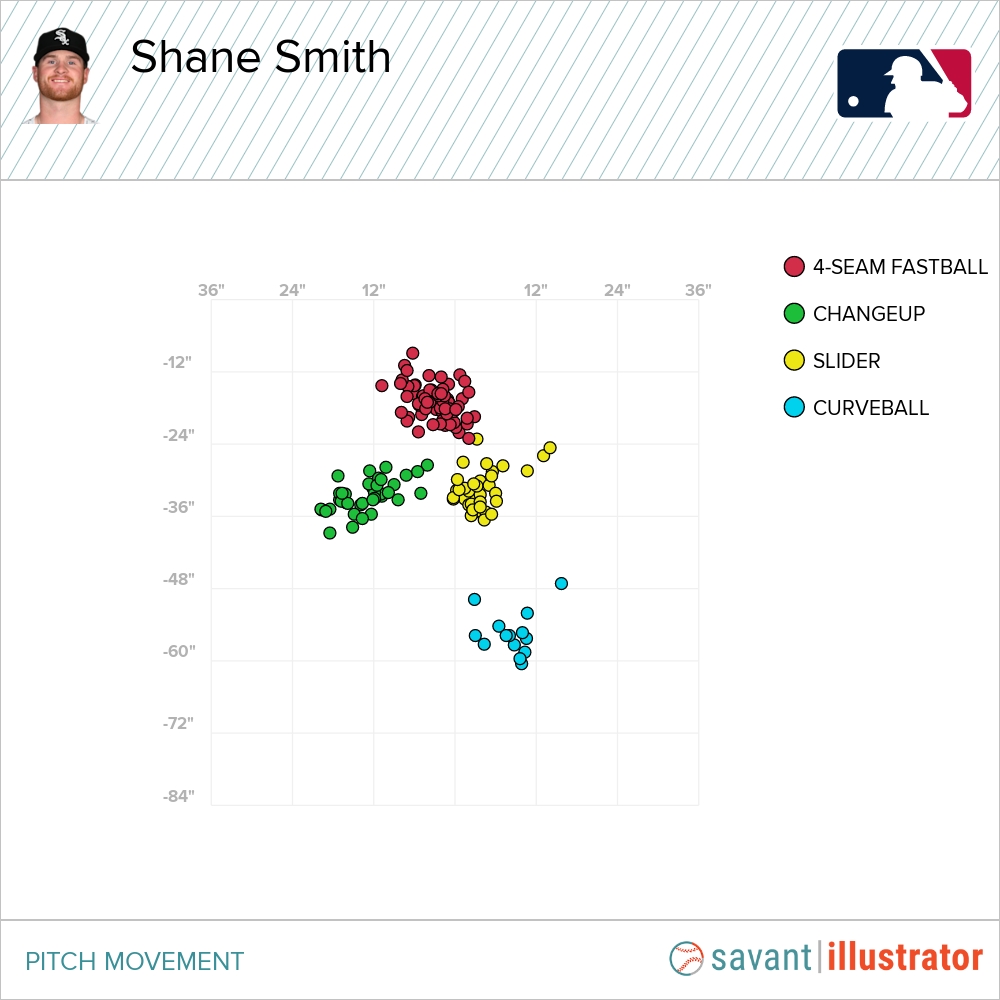

The second is that Smith is getting four distinct movement patterns on all four of his pitches, across three clear velocity bands. The four-seamer rises in the mid-90s, the changeup breaks arm side and the slider breaks glove side, both in the upper 80s, and the curveball drops like a brick in the low 80s.

As much as I’m still inclined to be circumspect after two starts, I don’t see anything here that says Smith can’t be an average major league starter. For a team with as many needs as the White Sox have, that’d be a massive coup. For such a massively underexperienced Rule 5 pick, it’d be nothing short of astonishing.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

Love this article. Thanks