Talk Thirty to Me: Why Veteran Talent Means More Than You Think

MLB front offices often spend a lot of energy trying to make their rosters younger. There are a number of obvious benefits to this — young players are cheap, especially before they reach arbitration status, and as Ben Lindbergh of The Ringer detailed back in August, they are also historically good. Trying to get younger is a strategy that’s easy to sell a fan base on, and yet during last month’s World Series, older players were the ones who often found themselves at the center of the attention. Sure, Washington’s preternaturally gifted Juan Soto took October by storm while turning just 21 years old during the World Series, but mostly it was guys like Howie Kendrick (36), Kurt Suzuki (36), and Ryan Zimmerman (35) catching headlines throughout the postseason. Veteran pitchers like Fernando Rodney (42), Anibal Sanchez (35) and Max Scherzer (35) were playing big roles for the championship-winning Nationals, while Justin Verlander (36) and Zack Greinke (36) each made two World Series starts for the runner-up Astros.

The idea of older players being the driving force behind these title contenders didn’t simply arise from a few random flashes of brilliance in October. According to ESPN, Washington reached the postseason with MLB’s oldest active roster. In fact, each of the five oldest teams in baseball reached the postseason, along with seven of the top eight. Some places show slightly different figures for average team age, but regardless of where you look, the top of the list always features a long list of teams who won a lot of games in 2019.

The easy headline here is that baseball’s best teams were also its oldest. But teams like the Nationals and Astros didn’t just have a bunch of old guys on their team — they had a bunch of very good old guys. The Yankees did too, and so did the Dodgers. After a long offseason that saw the majority of teams seemingly turn their noses up at veteran talent, older players produced as much value this season as they have for years. The difference was, in 2019, it was only a few teams reaping the benefits.

With all the discussion surrounding the veterans in the World Series, along with the entire postseason, I was curious as to whether there was any correlation between veteran talent and overall success this season. For reasons I’ll get into later, I was specifically interested in players at and above the age of 30. I looked at each team’s overall WAR totals and split them into two groups: WAR from players who were younger than 30 years old on June 30, and WAR from players age 30 or older. Here are those totals, with playoff teams highlighted in yellow.

| Team | WAR |

|---|---|

| Astros | 64.51 |

| Dodgers | 58.83 |

| Twins | 54.98 |

| Yankees | 50.87 |

| Nationals | 48.34 |

| Rays | 48.28 |

| Athletics | 47.21 |

| Red Sox | 43.96 |

| Mets | 43.85 |

| Cubs | 41.89 |

| Indians | 41.59 |

| Braves | 39.22 |

| Cardinals | 37.94 |

| Diamondbacks | 37.31 |

| Brewers | 37.03 |

| Reds | 29.71 |

| Phillies | 29.25 |

| Padres | 28.90 |

| Angels | 26.07 |

| Rangers | 23.45 |

| White Sox | 23.35 |

| Mariners | 22.26 |

| Blue Jays | 20.58 |

| Pirates | 19.68 |

| Giants | 17.55 |

| Royals | 17.02 |

| Rockies | 16.84 |

| Orioles | 11.90 |

| Tigers | 8.64 |

| Marlins | 8.59 |

| Team | WAR |

|---|---|

| Twins | 41.53 |

| Astros | 38.85 |

| Dodgers | 37.35 |

| Rays | 35.39 |

| Cubs | 32.06 |

| Mets | 31.93 |

| Red Sox | 31.32 |

| Athletics | 31.24 |

| Indians | 31.19 |

| Cardinals | 26.86 |

| Reds | 26.77 |

| Angels | 26.65 |

| Padres | 26.14 |

| Yankees | 25.90 |

| Braves | 25.52 |

| Phillies | 23.54 |

| Nationals | 23.32 |

| White Sox | 23.21 |

| Diamondbacks | 22.94 |

| Brewers | 19.62 |

| Blue Jays | 18.38 |

| Rockies | 18.12 |

| Pirates | 17.49 |

| Mariners | 15.37 |

| Orioles | 12.05 |

| Marlins | 9.46 |

| Royals | 9.20 |

| Rangers | 8.94 |

| Giants | 7.93 |

| Tigers | 7.72 |

| Team | WAR |

|---|---|

| Astros | 25.66 |

| Nationals | 25.02 |

| Yankees | 24.97 |

| Dodgers | 21.48 |

| Brewers | 17.41 |

| Athletics | 15.97 |

| Rangers | 14.51 |

| Diamondbacks | 14.37 |

| Braves | 13.70 |

| Twins | 13.45 |

| Rays | 12.89 |

| Red Sox | 12.64 |

| Mets | 11.92 |

| Cardinals | 11.08 |

| Indians | 10.40 |

| Cubs | 9.83 |

| Giants | 9.62 |

| Royals | 7.82 |

| Mariners | 6.89 |

| Phillies | 5.71 |

| Reds | 2.94 |

| Padres | 2.76 |

| Blue Jays | 2.20 |

| Pirates | 2.19 |

| Tigers | 0.92 |

| White Sox | 0.14 |

| Orioles | -0.15 |

| Angels | -0.58 |

| Marlins | -0.87 |

| Rockies | -1.28 |

The difference in the second and third table was interesting to me. There are unsurprisingly a bunch of playoff teams at the top of all three lists, but when it comes to teams who got a ton of value from players in their 20s, there are as many non-playoff teams in the top 12 as there are playoff teams. Missing the playoffs didn’t mean these teams were bad — the Cubs and Indians were in the mix for the entire year, while the Mets won 86 games and the Red Sox won 84 — but they were ultimately a step down from the other contenders. The third table, meanwhile, shows a much tighter pack of playoff squads at the top. The top six teams in that table all reached the postseason, and the Cardinals were the only playoff team not to finish in the top 11. There’s arguably a stronger correlation between WAR from players 30 and older and reaching the postseason than there is for overall WAR. Even for just one season, that’s unexpected.

The number 30 here might seem a bit arbitrary — round and convenient, an aesthetically pleasing cut-off point, but probably not substantially different from, say, 29 or 31. The reason I chose it is because of what it represents. It’s about the age when many players are first hitting free agency, or at least, when their service time would have dictated they reach free agency had they not signed an extension. Players who are 30 or older are much more expensive than their younger peers despite providing similar value. A player who is 30 or older is also a lock to make his team older and is less likely to break out in the future than someone in their 20s.

If a player can’t make a team younger, and he can’t make a team cheaper, he has to fulfill a third purpose — helping his team win games. That last task seems like it should be of considerably more importance to someone who’s putting together an MLB roster, but as we’ve witnessed with the last couple of free agent classes, most teams don’t seem to feel that way. Teams projected to be at or near the bottom of their divisions sell off anyone who doesn’t meet the goals of being young and cheap, and teams in the middle of the pack are much more comfortable going young and cheap than they are taking a risk on an older player who might buy them two wins. Even organizations with a track record of winning and spending money, confoundingly, have opted to go younger and cheaper at the cost of championship pursuits.

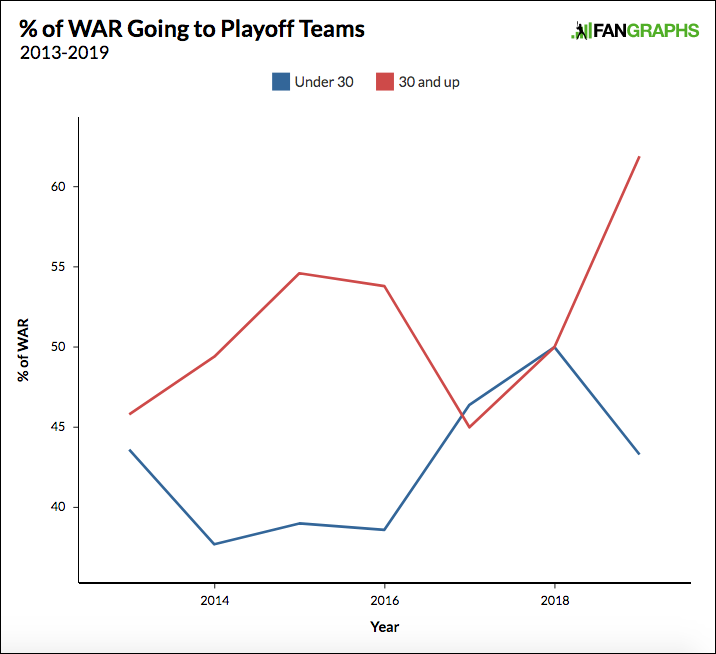

The result is a league in which there is a small number of contenders who believe themselves to have enough incentive to go get players who are in the second half of their careers and come with a higher price tag. That seemed anecdotally true throughout the season, and when looking at the share of WAR going to playoff teams over the past few years, it turned out to be accurate. Since the second Wild Card was introduced in 2013, just under half of all WAR accumulated across baseball has been compiled for teams who reached the playoffs. That stayed true for younger talent in 2019, with postseason teams benefiting from 43.3% of all WAR posted by players age 29 and younger. Their share of value posted by players 30 and older, meanwhile, soared.

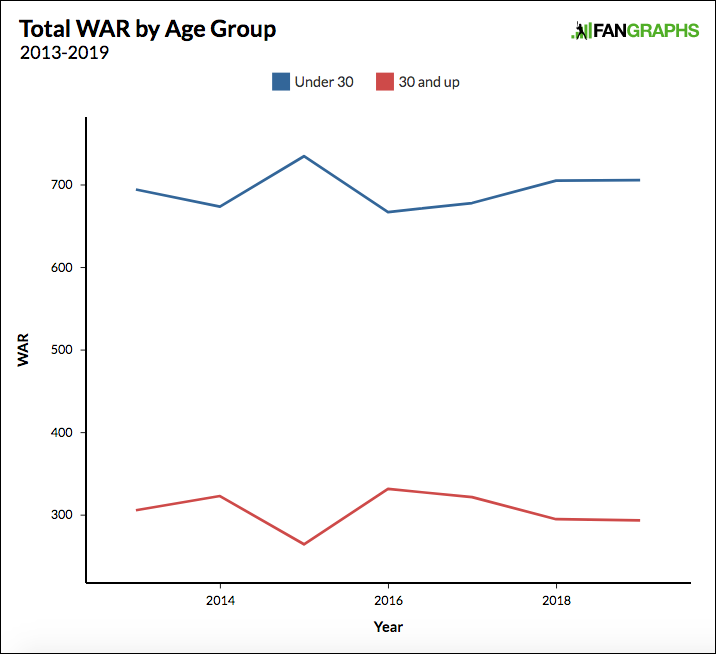

An astounding 61.9% of all WAR compiled by players 30 and older went to the 10 playoff teams. That’s three-fifths of a major chunk of value across baseball getting hoarded by one-third of the teams. You might wonder if this could simply be the result of fewer veterans being given chances around baseball, thus allowing the value posted by the ones who do to stand out more. But that isn’t the case. Players age 30 or older combined to produce about as much value in 2019 as they averaged over the last few seasons. The pot was just split by fewer teams than it should be.

WAR is a finite statistic. Every year, about 1,000 wins are distributed across all players in baseball. There will never be a surge in leaguewide WAR, like there has been in homers and strikeouts, nor will there be a sudden drop, like there is in stolen bases. There is just 1,000 WAR sitting out there at the start of every year, waiting to be claimed. And despite the efforts by front offices to get younger, and the all-time great production by the youngest players in the game, somewhere around 30% of all those WAR has continued to go to players who are 30 and older. That means building a team exclusively around players in that age range is still unwise — even the Nationals, as deep as they were in older talent, got four of their five most valuable position player seasons from players in their 20s this year — but it also means it’s extremely hard to build the most complete team possible while ignoring those older players and refusing to make the signings or trades necessary to get them on your team.

Each year, this truth is reflected in the postseason field. Dating back to 2013, if your team finished in the top 10 in WAR from players over 30, there’s a 62.9% chance you made the postseason (44 out of 70 teams). If you finished in the top 10 in WAR from players 29 and younger, your odds of making the playoffs were 57.1%. Complementing your good young players with good older players in important, and the good news for front offices is that this is the easiest part. Developing a great young core, whether it’s through the draft or clever trades or the international signing pool, is very difficult. It takes an incredibly smart group of decision-makers to hit on enough prospects to build a formidable force of young and — ugh — “controllable” major league talent, and even then, you’re relying a whole lot on luck.

But to cash in on this whole other segment of value, all you need to do is write a check. On our list of the top 50 free agents available this winter, 44 of them are 30 or older. They aren’t going to be better simply as a result of their age, but it does mean they’re maybe going to be overlooked because of it. Players over 30 are going to amass hundreds of wins in 2020, just like they always do. Allowing just a few teams to continue hoarding the majority of those wins for themselves will only further the gap between baseball’s superteams and the rest of the field.

Special thanks to Sean Dolinar for research assistance.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

What this tells me is that playoff teams have spent on free agents lately, and non playoff teams have not (because that’s how you get old players for the most part.) It doesn’t surprise me that teams that don’t consider themselves contenders wouldn’t sign free agents.

What happens when you eliminate all teams that are in rebuild mode? I feel like that would be more telling.

Non-contenders also trade their 30+ good players to contenders for prospects. This is similar to the shallow correlation between Payroll and Wins that Craig Edwards and others mistake for causation. Wins from a young core come first, then Payroll expenditures go up including those on 30+ yo’s to make those teams better contenders.