Taylor Walls, Pinch-Hitter

Taylor Walls, pinch-hitter. Pinch-hitter Taylor Walls. I keep turning the words around in my head, like a mantra. Taylor Walls, pinch-hitter. Walls, Taylor: hitter, pinch. Sometimes it makes more sense to me, sometimes less; over enough time, anything you repeat enough seems to lose all meaning. It’s called semantic satiation: your brain starts to perceive anything as gibberish if it’s repeated frequently enough.

In this case, I’m not even sure the phrase made sense in the first place. Taylor Walls, pinch-hitter? This guy? The one who hit .172/.268/.285 this year? In the game to hit? It sounds strange right from the jump. Maybe I started from a faulty premise somewhere. Maybe pinch-hitter Taylor Walls only exists in my head. Maybe this is all a strange fever dream.

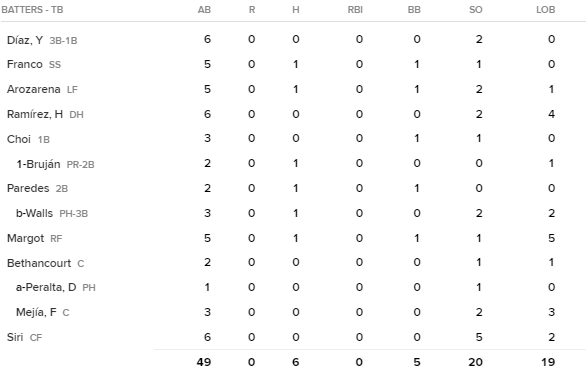

Only, it’s not. There’s box score evidence of it, right on MLB.com:

There he is, pinch-hitting in a playoff game. He’s hitting for Isaac Paredes, a right-hander, which gives us our first piece of evidence. Walls is a switch-hitter. Surely, then he came into the game to bat left-handed. Indeed he did: he faced off against Nick Sandlin, a right-handed reliever, in that initial plate appearance.

Handedness matters. Left-handed hitters get a boost when hitting against righty pitchers; right-handed hitters face a penalty. The Rays love boosts and hate penalties, naturally enough. Can we write it off as a platoon situation and call it a day?

We cannot. To explain why that’s not enough reason, let’s reduce the rule to an absurdity. I am left-handed. That’s just a fact. I’m also a worse option than Paredes to face Sandlin. I’d be a worse option than sending up a right-handed pitcher off the bench to face Sandlin. Being left-handed isn’t enough. Having a platoon advantage helps, but it doesn’t override skill.

Taylor Walls, pinch-hitter. Taylor Walls, pinch-hitter. Taylor Walls… pinch-bunter? Maybe Walls was up there trying to drop down a sacrifice bunt and manufacture a run. After all, the Rays had just brought on Vidal Bruján, their best pinch-runner, at first base. Get him into scoring position, and most base hits could break the scoreless tie.

Indeed, Walls showed bunt late on the first pitch:

Now, I’m not convinced that Walls is a premium bunt artist. He’s successfully converted a sacrifice bunt only five times in his professional career. Paredes, for his part, has 10, though only seven in the last two years. With Bruján on base, though, you don’t need to be a great bunter; merely putting the ball in play on the ground would likely be enough.

Or would it be? The Guardians aren’t some inert robot, sitting there in the field motionless as Tampa Bay schemes. Before the 0–1 pitch, José Ramírez took several steps toward home:

That act cut down on Walls’ margin of error significantly. Ramírez is an excellent defender; Walls, as I mentioned, is an indifferent bunter, at least to the extent that we can tell from major and minor league data. True to form, he gave up on his bunting plan and swung away on 0–1:

As you can infer from Austin Hedges, Bruján was on the move. The Rays decided to try to take second via stolen base, leaving Walls to swing away. Indeed, for the rest of his time at the plate, Walls never so much as showed bunt, and the Guardians backed off into a normal defense. Whatever the Rays wanted Walls for, it wasn’t really bunting, or they would have tried more than a cursory disguised bunt on the first pitch. In the end, Walls struck out, though Bruján took second anyway:

That just brings the initial question back into focus: why did Tampa Bay prefer the Walls-Sandlin matchup to the Paredes-Sandlin matchup? Paredes had a 106 wRC+ against righties this year. He has a career 85 wRC+ against them, in a small enough sample size that it’s likely to mainly be noise. A regressed estimate of his platoon skill would suggest he’s a roughly league average hitter against righties. Walls has a career 69 wRC+ against righties, and it’s not some weird artifact of platoon splits; he has a career 70 wRC+ overall.

Is Sandlin a particularly bad matchup for Paredes? He’s mostly sinker/slider, with a sweeping breaking ball. He throws the occasional four-seamer, but they look mostly like slightly-shifted sinkers; they have a lot of horizontal run and not very much ride relative to a “textbook” four-seamer. Paredes struggled against right-handed sliders this year, as did most right-handed hitters. He didn’t appear particularly susceptible to the sweeping variety, posting similar numbers against sharp and sweeping sliders, but it’s fair to expect that Sandlin would throw more or less nothing but sliders in any case. Paredes’s best defense against sliders is taking them; he only offered at 18.8% of out-of-zone righty sliders this year, much better than league average. If Sandlin could locate the pitch, though, it would probably be a good matchup for Cleveland.

Walls, on the other hand, holds up well against sliders. Many switch-hitters do; they always have a platoon advantage against the pitch, and sliders demonstrate a larger platoon split than any other pitch type, particularly sweeping sliders. That eliminated one of Sandlin’s best pitches. But Walls struggled against sinkers this year and fastballs in general. That’s been true throughout his brief major league career. The Rays were likely exchanging sliders to Paredes for fastballs to Walls.

It’s clear that the Rays weren’t that worried about letting Paredes face right-handed pitchers with sliders. He started, which is why he was in the lineup to be pinch-hit for. Cleveland’s starter that day? You guessed it: Triston McKenzie, a righty who throws a slider. McKenzie’s slider is more sharp than sweeping, but as I mentioned earlier, Paredes posted equal numbers against both varieties of slider. He’d performed quite well against the pitch so far on Saturday, for what it’s worth; he took a handful out of the zone for an early walk and fouled off the only one he swung at.

My guess is that the Rays were dead set on avoiding the Sandlin/Paredes matchup. They weren’t afraid of using Paredes against tough righties; they’d literally pinch-hit for Walls with Paredes against Shane Bieber the previous day. Perhaps it was a situational decision with two outs and the bases empty against Bieber, and Paredes having far more power. But it’s not like Walls is the superior on-base play; he struck out more often than Paredes and walked less frequently. It wasn’t a right-hander, then: it was Sandlin specifically.

Those single-season numbers aren’t the end-all be-all. Maybe the Rays were 100% certain that they needed to avoid the Paredes-Sandlin matchup. Maybe they were selling out for contact with Bruján on the basepaths. If that’s the case, Paredes isn’t a great fit: he takes a lot of pitches, and though he’s not a big swing-and-miss guy, when he puts the ball in play, it’s often in the air. Maybe they were optimizing for something obscure, like grounders plus line drives per plate appearance. Except, that can’t be it: Paredes checked in with a higher mark than Walls there despite a fly ball approach and a shockingly low line drive rate, because he doesn’t strike out very often. So that brings us back to the team being completely unwilling to let Paredes face Sandlin. Nothing else makes sense.

Taylor Walls, though! We’re not trying to figure out why Paredes left the game. We already know why: to get Walls into the batter’s box. But why did Kevin Cash turn to Walls specifically? He had Jonathan Aranda, a left-handed thumper, still available as the last man on the bench. To prefer Walls in that spot, the team had to think he was more likely to get on base than Aranda, and I don’t think that’s the case.

Aranda never came into the game, though Walls batted twice more, once against a lefty and once against a righty. In fact, Tampa Bay didn’t use Aranda at all; he would have had to pinch hit either for Walls or Manuel Margot given the players remaining, and neither matchup appealed to them.

Maybe the Rays were in a defensive bind. Walls stayed in the game to play third base. But Aranda can do that, too, racking up 300 innings at the hot corner between Triple-A and the majors this year. Walls is a better defender, but you have to score some runs before you can protect a lead. In any case, there was always the option to bring Walls in as a defensive substitution. They clearly didn’t need that last player on the bench; Aranda never entered the game, after all.

Did I solve it? I don’t know. My best guess is that there was just a giant blinking red light in the Rays’ matchup grid that told them to avoid letting Paredes face Sandlin under any circumstances, and that Cash preferred Walls to Aranda for a pinch-hit appearance. They couldn’t have known the game would drag on for 15 innings, or that Walls would bat three times. They couldn’t have known he’d bunt that first pitch foul, or that Bruján would get several clean jumps off of Sandlin, granting the team second base without a sacrifice.

All of that is ex-post thinking. But the fact remains: the Rays used Taylor Walls, who was their worst hitter this season and one of the worst everyday regulars in the majors, to replace Isaac Paredes, who was one of their best. Walls struck out. The Rays didn’t score any runs. If you’re looking for a four-word summation of what went wrong for Tampa Bay in 2022, you could do worse than “Taylor Walls, pinch-hitter.” When the chips were down, he was the best the Rays could bring to bear. It wasn’t enough.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Homer at bat.