The Complicated Mix That’s Hurting Juan Soto

In no world is Juan Soto is having a bad year. Through games played on Saturday, he has more walks than strikeouts, a 128 wRC+, and a .272/.404/.426 triple slash in 240 plate appearances. He’s been worth 1.6 WAR in 58 games, thanks at least in part due to improved defense; ZiPS projects him to add another 3.5 wins the rest of the way, which would result in a career-high 5.1 WAR. Even at his current pace of 4.5 WAR, Soto would end the season as one of the more valuable players in baseball.

By his standards, however, Soto is actually having a bit of a down year. That 128 wRC+ I mentioned? That is just above his worst mark in any 58-game stretch (127) of his entire career. It still represents great production in a vacuum, and the fact that his worst wRC+ still is 127 is just another way to underscore his greatness. But at the same time, it still leaves us with a lot of questions, none more important than this: Why has Soto seen such a notable decrease in performance?

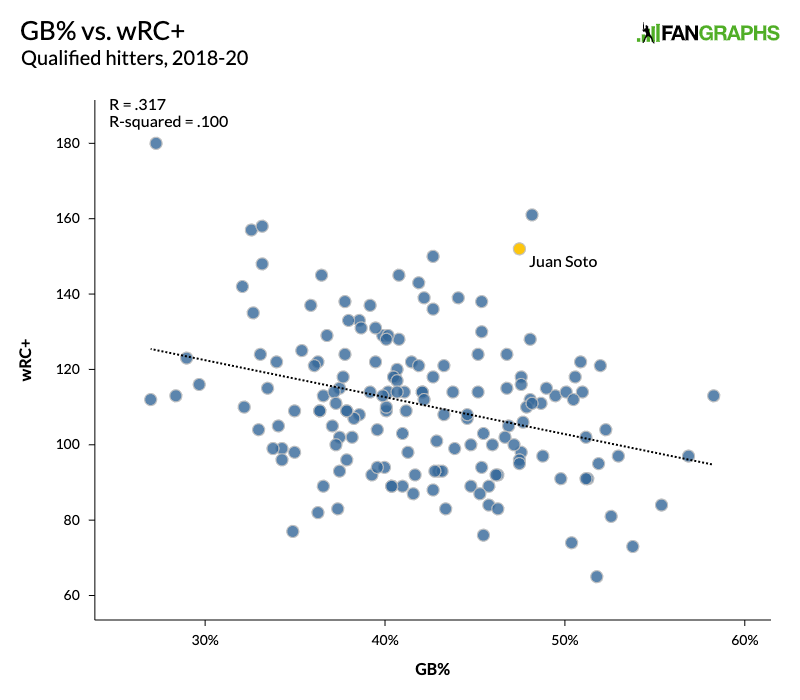

The answer might seem somewhat simple: He’s hitting far too many groundballs. Soto currently has a 55.3% groundball rate, seventh-highest in the majors. The fact that he’s still posting a 128 wRC+ in spite of that is borderline absurd; of the 30 qualified hitters with at least a 48% groundball rate, he has the highest wRC+, a testament to his phenomenal plate discipline and frequency of hard contact.

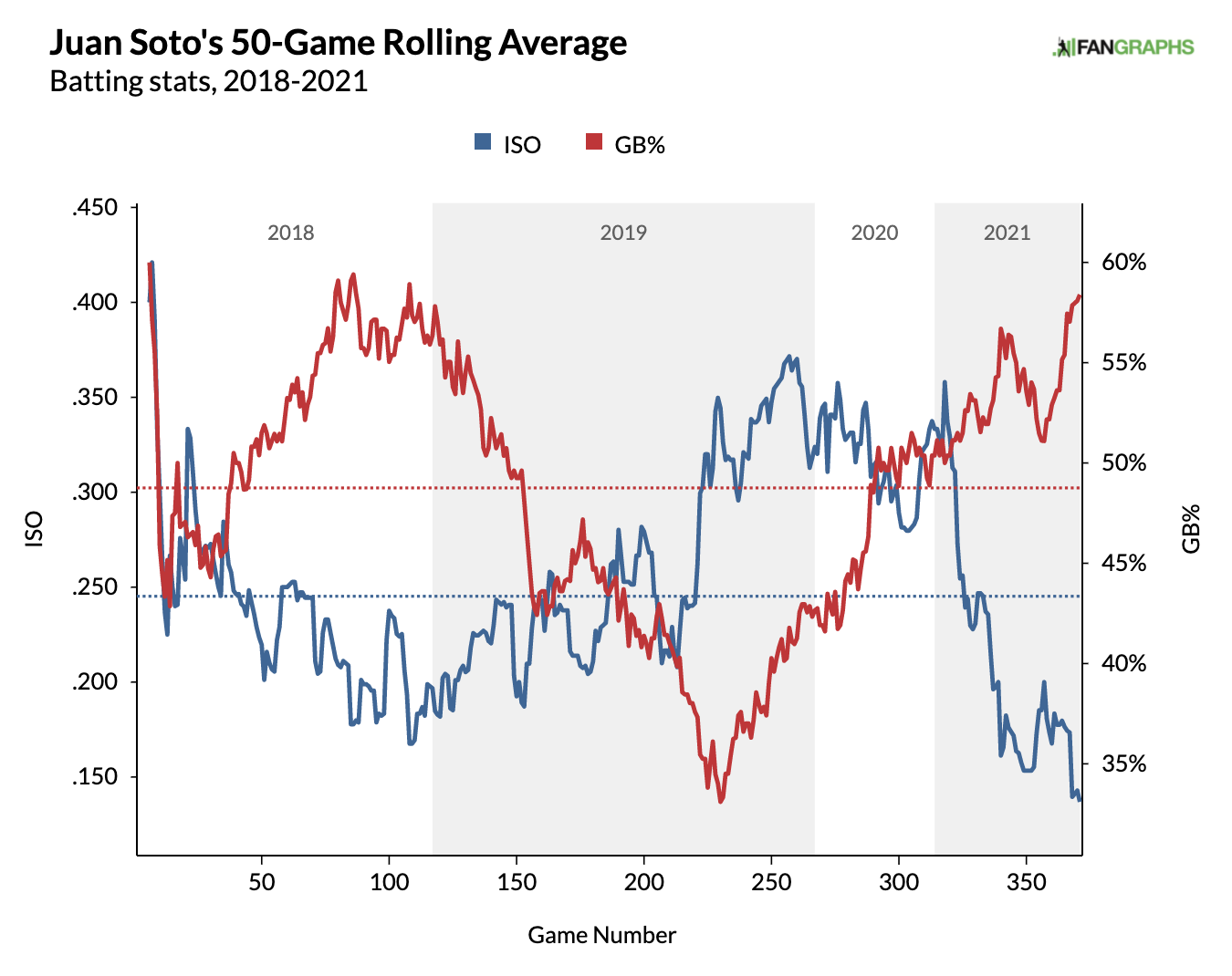

As a result of all of these grounders, Soto is embarking on Vladimir Guerrero Jr.’s 2020 journey. But while Vlad Jr. is currently elevating and celebrating this year, Soto is grounding and outing. Bad attempt at a rhyme aside, his groundballs mostly turn into outs. The ones that aren’t outs? They are singles, and they the reason why he has experienced a personal power outage. In his last 50 games, he has a .137 ISO, another career low for a sample that large.

In mid-May, Soto himself recognized that groundballs have become an issue, explaining to reporters, including Jesse Dougherty of The Washington Post, that he was working with Nationals hitting coach Kevin Long to make adjustments. “We’re trying to put the ball in the air,” Soto said. “We’re just trying to put the [bat] head out, put the barrel out to the ball and then see how far it can land.”

Soto acknowledged that he had been dealing with a timing issue following his activation from the injured list on May 4. In the 61 plate appearances before he went down with a strained left shoulder, he slashed .300/.410/.460 with a 134 wRC+, but more to the point, his groundball rate of 47.7% was right at his career average coming into this season. Since, however, that’s jumped to 58.3%, the fifth-highest rate in baseball in that stretch.

What’s interesting about Soto, though, is that a high groundball rate both isn’t necessarily new for him and also traditionally hasn’t come back to bite him. From 2018 to ’20, his groundball rate ranked in the 79th percentile among major league hitters, even though he posted a 152 wRC+ in that stretch:

Last season, his groundball rate reached new heights, with more than half of his batted balls being hit on the ground for the first time in his career even as he posted a 201 wRC+ — two facts that appeared to be incompatible, at least to me. I actually wrote about Soto’s excellent results despite his high groundball rate, noting that while I wasn’t too concerned at the time, “this could be something to watch in the future.”

Looking back at the data, it’s more clear to me now how Soto was able to maintain a high groundball rate while still having one of the best, albeit shortened, offensive seasons in recent memory. First, he posted a .248 wOBA on groundballs last season. That’s not a sterling figure by any means, but it’s still plenty passable given how often he walked, limiting the number of balls he put in play to begin with. When he did put the ball in play, it was in the air still roughly half the time.

But as I mentioned, Soto’s groundball rate was something to monitor, and two things have changed for him this season. First, as mentioned throughout, his groundball rate is up again. Second, teams are shifting him way more, and it’s pretty clear that this is having a significant impact:

| Year | Standard% | Standard wOBA | Standard xwOBA | Shift% | Shift wOBA | Shift xwOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 62.7% | .311 | .232 | 26.9% | .098 | .292 |

| 2021 | 27.3% | .110 | .260 | 59.1% | .177 | .248 |

There’s a lot going on here, but this demonstrates the crux of Soto’s problem in multiple ways. First, his batted ball quality when shifted versus when played straight up is roughly equal. Second, he’s struggled this season compared to last because he is shifted more and because, when not shifted, he has underperformed his expected wOBA by 150 points. The combination of these two factors has resulted in one of the larger xwOBA/wOBA differences in baseball, and the issue of results versus batted ball quality has been exacerbated by how often he hits ground balls. Among the 200 hitters with at least 50 groundballs this season, he has the 41st-largest xwOBA/wOBA difference but the 28th-largest difference after weighing the number of groundballs that this has impacted. That’s a not-so-insignificant change.

To be sure, Soto has also dealt with some bad luck on other types of batted balls as well. A hitter does not lose more than 100 points of wOBA year-over-year just because their groundball rate jumped four points. When he does put the ball in the air, he is rarely rewarded, and that’s a problem that should theoretically get ironed out in a larger sample. Among the 233 hitters who have hit at least 25 fly balls this season, he has the third-largest xwOBA/wOBA difference, with a staggering 238-point differential. His .713 xwOBA on fly balls is the 13th-highest among this group; his .477 wOBA ranks 110th.

But we can’t conclude that Soto’s extreme differential between his expected and actual stats on fly balls is what is driving his performance dip, and it comes down to sample size yet again. He has hit just 29 fly balls this season but 88 ground balls, so while there is an extraordinarily high disparity between his expected and actual stats on fly balls, it doesn’t actually account for all of his struggles. If you award Soto a .713 wOBA on his 29 fly balls this season, his seasonal wOBA jumps to .391. That’s a 30-point improvement from where it is now, but it is still 30 points below his expected wOBA figure of .421 and 87 points below his 2020 wOBA of .478. Bad luck on fly balls (if you want to call it that) does matter here, but perhaps by not as much as you’d think considering how few batted balls it actually affects.

To isolate the effects of the shift on Soto’s performance, we can conduct a similar exercise. If we award Soto a .260 wOBA on the 24 groundballs he hit when played straight up, his wOBA on groundballs would jump to .235. Here, too, we’ll give him the .713 wOBA on the 29 fly balls, and he’s now working with a .406 wOBA overall. What’s interesting here is that a .406 wOBA is roughly in line with his rest-of-season projections; ZiPS has him at .409, and Steamer has him at .405. It is still 15 points below his expected wOBA and 72 points below his 2021 wOBA, but does look a lot more like what we have come to expect from Soto.

The problem with this analysis, though, is that it assumes that the shift is the only reason why Soto’s underperforming his expected statistics on groundballs. Is the 150-point differential when played straight up explained only by luck? It’s possible, but it’s also likely that there’s more to explore there.

Either way, it seems like Soto still needs to elevate more. He was never going to repeat his 200 wRC+ season again in 2021 — and it’s clear that he was aided by some good fortune, much of which has reversed this year — but if he wants to be more successful, he’ll need to hit more fly balls than he is right now. That’s not to say he’s not successful in the moment. That’s the beauty of Juan Soto: anything and everything can be considered a nitpick. He’s a phenomenal player, and even when having a down year, he’s still producing well-above-average results.

Devan Fink is a Contributor at FanGraphs. You can follow him on Twitter @DevanFink.

Soto had been the antidote to the TTO plague- his first couple seasons he was great at spraying the ball in the air. He was impossible to shift and did a great job of exploiting what the pitcher wanted to do. Later in the 2019 season, he was clearly trying to pull the ball more early in the count. That seems to have made him more vulnerable to good pitches and while he can still mash a mistake, most teams will pitch around him and face a lesser evil.

Kevin Long has gotten great mileage out of hacking Daniel Murphy. Teams have adjusted and that launch angle inefficiency is not as valuable. The ability to not make an out (let alone two) remains the most valuable commodity and once Soto starts driving those early count offspeed pitches away into left, the ISO numbers will tick back up. He’s not a pure power guy (yet) like Freddie Freeman, but they have a lot of the same tools.

Right now, he’s being attacked as an opportunity as opposed to a threat.