The Impossible Quest for Im-Morton-ality

Charlie Morton has been about to retire for a while now. The lanky curveball specialist first made headlines in the early 2010s; he’d been struggling over his first three major league seasons, so he came up with a novel, but hilariously simple, solution: Copy what Roy Halladay was doing. It worked for a while, but injuries piled up, and it wasn’t until Morton landed with the Astros in 2017 that he really, truly put it together.

In the first season of a two-year deal with the Astros, Morton set new career highs in wins, WAR, and strikeouts. He not only won a championship for the first time in his career, he was the winning pitcher in Game 7 of both the ALCS and the World Series, and got the last out of the season in the latter case. He turned 34 five days after the Astros’ championship parade, and by the following spring he was already musing publicly about hanging up his spikes.

In April 2018, he told Jake Kaplan of The Athletic that he might retire once his contract expired at the end of the season. I’ll quote a larger-than-normal chunk of his explanation, because you don’t usually see this kind of candor from athletes:

“I miss my family. Family is the most important thing to me. My wife has been incredible with how she’s handled the change to becoming someone that is basically a support system. She had dreams of what she wanted to do with her life, and I’m sure it wasn’t moving to wherever I was and revolving her life around what I was doing. But that’s exactly what happened. And we’ve been really fortunate financially with the success I’ve had in my career. But it’s not like I want to keep playing just to keep playing. Because I’m cognizant of her needs and wanting to do something for herself and also our kids, who would prefer to have me at home. My goals in baseball have pretty much been fulfilled.”

That was seven years ago, and Morton is still pitching. This is not a guy who goes along to get along; Morton has a reputation not only for being smart, but for being his own man, doing things his way. If he’s still punching the clock at age 41, he must have a good reason.

I bet Morton would’ve called it quits years ago if teams didn’t keep throwing piles of money at him.

Morton made his first All-Star team in 2018 and hit free agency that winter. To that point, he’d earned about $40 million total in his career. But the right situation arrived in 2019: The Rays needed a veteran leader for a promising young staff that included Blake Snell, Tyler Glasnow, Ryne Stanek, and Brendan McKay, and they were willing to pay Morton a franchise-record $30 million contract for two years of work.

Nearly double your money and still retire at 36? That’s worth sticking around for. Morton led the Rays back to the playoffs in 2019 and finished third in the Cy Young voting. In 2020, he made it back to the World Series, but the Rays fell to the Dodgers in six games. Surely, this would be a good time to quit.

Then the Braves offered him $15 million for one more season. Morton pitched well in 33 starts and the Braves won the World Series. Another one-year contract followed, this one for $20 million, along with a 101-win season. Then a one-year deal for $20 million in 2023 with an identical team option for the season after.

In 2024, the Braves merely squeaked into the playoffs and Morton was only league average in his 30 starts. OK, now seems like a good time to pack it in and go back to the family farm.

Unless the Orioles want to offer another $15 million for one last year, no, we’re serious this time.

Morton has accomplished more after his 33rd birthday than most athletes do in a lifetime. The old man has legitimately been one of the best pitchers in baseball since 2017; he’s 13th in that time in WAR, ninth in innings, and fourth in strikeouts. Only eight other players at any position can match or beat Morton’s combination of two World Series rings and 22.0 WAR since 2017, and half of those players won at least one of their championships playing alongside Morton.

It’s been seven years since Morton first started to talk about retirement, and even longer since the start of this post, so I guess I’ll finally get to the point: It seems like the end is nigh.

Morton, now 41, has appeared in nine games for the Orioles this year. Baltimore is 0-9 in those games, and Morton has taken the loss an astonishing seven times. He’s allowed at least one run every time he’s taken the mound this year, and two or more earned runs eight times out of nine. Morton is now one of seven 21st Century pitchers, and the first since 2013, to be charged with seven or more losses in his team’s first 35 games.

It’s no surprise that Morton was demoted to the bullpen after five starts, with a 10.89 ERA and a 6.91 FIP. He’s since returned to the rotation for a spot start on Wednesday, and lowered his ERA to 9.38. Most distressing, Morton doesn’t seem to have an idea what’s gone wrong.

“It would be way easier if I was throwing 89-91 [mph] and my curve wasn’t spinning and my changeup wasn’t sinking and running and my cutter wasn’t consistent,” Morton told reporters after his last start. “It would be way easier just to go, ‘You know what, I don’t have it anymore. I just don’t have the physical talent to do it anymore.’ But the problem is I do.”

It’s true; if Morton is losing his fastball figuratively, he’s not losing it literally. His velo is down less than a third of a mile an hour from last year, a margin so trivial it would not even register under normal circumstances. His curveball, if anything, is breaking even more than it did in 2024. His elite breaking ball spin has changed neither in quantity nor in direction.

But he’s not getting ahead of hitters as much. He’s not hitting the zone as much, and when he does work within the zone he’s leaving a few more pitches over the middle of the plate. When he’s outside the strike zone, hitters are laying off; his opponent chase rate has dropped from 30.1% in 2023 to 28.8% in 2024 to 25.7% in 2025. His changeup, which averaged 85.0 mph last year, is now coming in 2.3 mph faster, with an inch and a half less horizontal run.

I’m with Morton here; I don’t see an obvious mechanical bump or technical collapse that explains how a league-average pitcher is now so far below replacement level he’ll get the bends if he regresses to the mean too quickly. More likely, it’s a combination of little things. That’s how time always gets us.

I long ago made my peace with being older than most ballplayers, adjusted my interview style to reflect the fact that most of the people I’m talking to weren’t alive for the canceled World Series of 1994 and don’t remember Tony Gwynn or Greg Maddux. At the draft combine, I’ve started running into players who were born after I graduated high school. People roughly my age are starting to filter into the ranks of GMs and POBOs. If you’re old enough to remember first-wave emo, you’re probably wearing a quarter zip to work, not spikes and mitt.

But I’ve always felt a small measure of comfort knowing that there are still ballplayers who are literally older than me. I don’t like that this is comforting; it is not only a vanity, it’s a useless vanity, and one shared by every baseball fan whose knees start to creak.

Those ranks are thinning out. I turned 38 the day before Opening Day, and so far this year, only 15 players my age or older have appeared in a major league game. And it hasn’t gone well, for the most part. Max Scherzer’s gotten hurt; Adam Ottavino, Yuli Gurriel, and Carlos Carrasco have already been DFA’d or released. Jesse Chavez has gotten DFA’d or released about 15 times already, and will probably get signed and cut twice more by the Braves before this piece runs.

Here’s one thing I remember that younger big leaguers probably don’t: A large group of players continuing to perform effectively in the majors into their 40s.

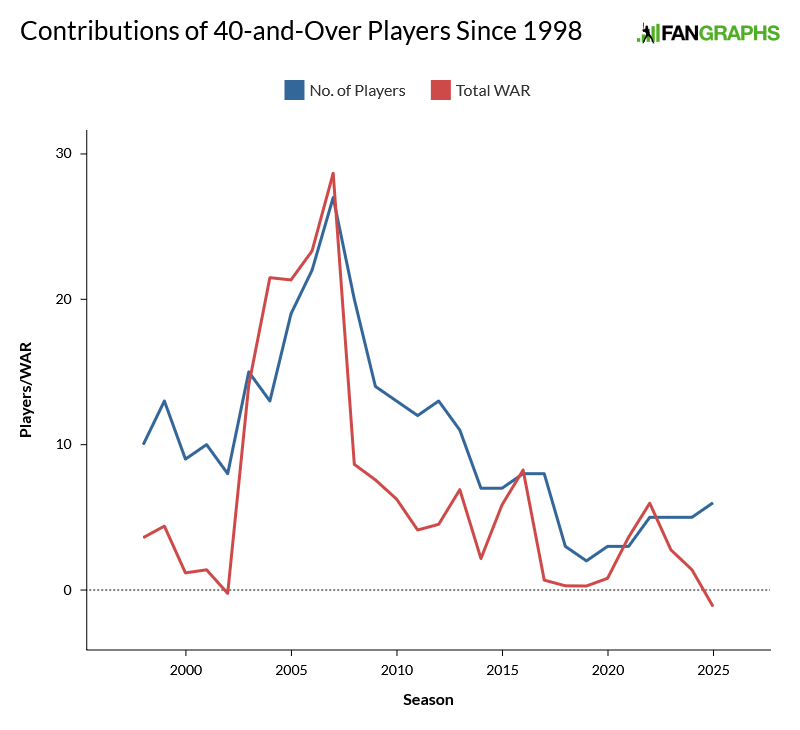

You can see it in the graph here. Six 40-and-over guys in the majors so far this year actually represents a bumper crop in the context of the 2020s, but they are far fewer in number and in quality than they were 20 years ago.

What’s changed? Well, you can see it in Morton’s ongoing retirement calculus. Salaries have exploded, which means players like Morton don’t have to keep grinding if all they can get is a minor league contract and a non-roster invite. It was only a month ago that Lance Lynn, a pitcher in a situation very similar to Morton’s, explained that he had offers to pitch in a big league rotation for millions of dollars, but the more he thought about it, the more it just wasn’t worth the trouble anymore.

Front offices’ understanding of the aging curve has evolved as well; we no longer count on Nelson Cruzes to keep producing when it’s clear that 21-year-olds can hack it in the majors. Especially because you might notice that the peak of that graph, and the decline to the trough we’re in now, lines up with the stigmatization of performance-enhancing drugs. Gone are the days when players can rip HGH with impunity and play until they’re 45 without missing a beat.

Morton might not know why he can’t get outs anymore, but it happens to everyone. He’s already been an outlier, an iconoclast, a holdout from a bygone age in more ways than one. Time is the only undefeated opponent; Morton outran it longer than most, but he was never going to stay ahead of the culling forever.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

Orioles were highly overrated.1 great player, and a bunch of overrated prospects

Starting to look that way. Stunned Elias hasn’t tried to flip anything for pitching. Worse run diff in the AL.

People can’t handle the truth