The Orioles Have Good Reason to be Excited About Trey Mancini

The MLB All-Star Game is just two weeks away, and the Baltimore Orioles have been campaigning hard for Trey Mancini to appear on the American League roster. This is understandable — at 22-58, the Orioles have given fans little to cheer for this year, and Mancini is rather unambiguously the best player on the club. Teammate Chris Davis has been vocal in his support for Mancini, and the organization went so far as to put together a full-fledged (if tongue-in-cheek) campaign video for him.

Baltimore’s enthusiasm surrounding Mancini’s All-Star candidacy helps draw attention to what has been a fantastic bounce-back season for the 27-year-old. He owns a .303/.362/.557 line and a 139 wRC+, good for 24th-best in the majors. His 7.9% walk rate and 19.5% strikeout rate are both career bests, and his xSLG, xBA, and xwOBA figures each put him in the 87th percentile of all major leaguers or better.

That set of numbers contrasts sharply with where we found Mancini in 2018. He smacked 24 homers for a second year in a row, but that was the lone bright spot in an otherwise underwhelming offensive season. He hit just .242/.299/.416, posting a 93 wRC+ and 0.29 BB/K figure. Because Mancini was a nightmare in the field — his -17.2 defensive runs above average were the fifth-worst in baseball — he finished the season as a sub-replacement level player. In most other organizations, he likely would have lost his starting job, but on the talent-bereft Orioles, he’s gotten a second chance. How has he made the most of it?

Like so many other hitters who have experienced this kind of breakout in recent years, the answer seems to lie in his groundball and fly ball rates. Prior to this year, Mancini hit far too many grounders for a power hitter, posting a 54.6% groundball rate in 2018 that ranked seventh-highest in baseball. This year, that number is down to 42.5%. Lowering one’s groundball rate in a trendy practice across the game, but Mancini has done so at a different level from almost anyone else:

| Player | Team | 2019 GB% | 2018 GB% | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ian Desmond | Rockies | 44.8% | 62.0% | -17.2 |

| Trey Mancini | Orioles | 42.5% | 54.6% | -12.1 |

| Cody Bellinger | Dodgers | 28.6% | 40.0% | -11.4 |

| Ketel Marte | D’backs | 40.9% | 51.2% | -10.3 |

| Michael Conforto | Mets | 33.5% | 43.8% | -10.3 |

Ian Desmond is in his own class here, which Devan Fink has covered on this site before, while Cody Bellinger and Ketel Marte’s respective transformations have made them into some of the most formidable hitters in the game. Mancini’s improvement has been just as dramatic, though it’s difficult to pin down the exact driving force behind it. His plate discipline profile is largely unchanged from last year, as is his pitch selection. Even his swing doesn’t appear much different from the one he had last year.

Here’s Mancini crushing a homer in 2018:

And a Mancini bomb in 2019:

Perhaps someone out there is more eagle-eyed than I am, but here’s what I see: The same feet and hand positions, the same stride, and the same pre-pitch fidgeting. Wherever you look, Mancini seems like the same hitter he was last year. Clearly, though, he isn’t.

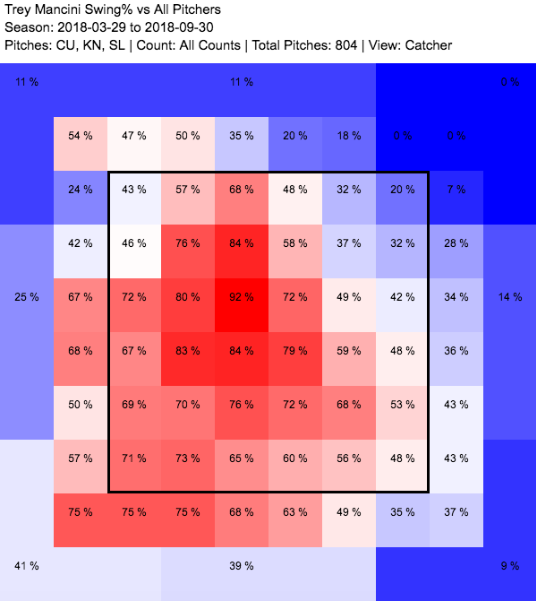

The closest we get to explaining Mancini’s new ability to elevate are his results against breaking pitches. According to Statcast, his launch angle is up from 3 degrees to 12 against breaking pitches, while his ground ball rate against them is down from 61.2% to 33.3%. That got me thinking about the parts of the zone where he was swinging at those offerings in 2019 compared to 2018, which brought me to this:

Again, these don’t provide us with much help. He’s swinging at pitches lower and further away from him this year than he was last year, pitches one would expect to be more difficult to elevate. And yet, here we are. Part of the confusion may have something to do with the fact that we’re clustering all breaking pitches together, since that’s the grouping the Statcast data afforded us. Obviously, however, we know all breaking pitches are not created equally, and singling out each specific pitch does bring us a bit more clarity.

| Year | wFB | wSL | wCT | wCB | wCH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 8.7 | -6.0 | -5.8 | 2.1 | -3.9 |

| 2019 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

Last year, Mancini was the second-worst hitter in baseball against the cutter, the 12th-worst against the changeup, and the 15th-worst against the slider. This year, he’s eliminated those weaknesses, grading out average against the slider while sitting firmly above average against the cutter and changeup. Most importantly, he hasn’t sacrificed much elsewhere, still mashing fastballs and holding his own against curveballs. In other words, he’s a hitter without any real weaknesses. It’s no surprise he’s having the best year of his career.

And Mancini just keeps improving. After a down month of May, he’s hit .315/.400/.603 in 85 plate appearances in the month of June, striking out just 12 times while drawing nine walks. That is something of a selective endpoint, but it is coming along at an important time. For fans of rebuilding teams, the month of July typically means waiting around to see which productive big leaguers are about to be shipped out of town, all while hoping the prospects being returned are worth dreaming on. Before that time comes, though, there is this neat little barrier put up by the All-Star game.

Every team, from World Series contenders to those in the middle of the pack to, well, the Orioles, gets to send at least one automatic representative, but that’s not how anyone wants their favorite player to make the team. Fans want to know that their representative is there because other fans and players and coaches around baseball thought he deserved to be there, regardless of whether he had any teammates worthy of joining him there. I know this, because I grew up a fan of the Cincinnati Reds, who went a span of five consecutive years (2005-2009) sending just one player to the All-Star game. The exhibition itself means nothing, but watching a player earn his spot on the team in the weeks building up to the game can be a thrilling occasion. The Orioles have won just one of their last 12 games, but Mancini has still given fans a reason to watch by posting a 1.115 OPS in that same span. He’s playing like a star. You can’t blame the rest of the organization for hoping more people take notice.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

Just my first observations on the swing: It looks like Mancini’s leg kick is less pronounced, and starts later in the delivery. I stopped the videos at 5.02 and 2.83 and it seems clear that Mancini used to start his leg kick when the pitcher’s hands split, whereas on the current swing he waits until closer to the pitcher’s landing point, where the throwing arm is more parallel to ground instead of perpendicular. I would think this helps his timing against breaking pitches, since he will be spending less time in a more difficult to balance position. We know big leg kicks are effective for fastballs (see Bautista), but perhaps this timing adjustment for Mancini is part of the cause for improvement in pitch recognition.