The Pitch Clock Is (Probably) Not Being Enforced in Spring Training

One of the more contentious issues facing Major League Baseball, the Major League Baseball Players Association, and baseball’s fans is the potential use of a pitch clock at the major league level.

The pitch clock, which has been in use in the minor leagues since 2015, was not among the wealth of changes announced in the latest agreement between MLB and the MLBPA, but it has been present and enforced during all of the 2019 spring training games played. Or so we think.

As it turns out, in MLB’s initial announcement of the spring training pitch clock, the league made one very important point:

Later in Spring Training, and depending on the status of negotiations with the Major League Baseball Players Association, umpires will be instructed to begin assessing ball-strike penalties for violations.

The pitch clock has seemingly been tabled in the mid-CBA rule change discussions, with Jeff Passan reporting in late-February that MLB will “scuttle the implementation of a pitch clock until at least 2022.” At least to me, that did not necessarily mean that the pitch clock would automatically go unenforced during the remainder of spring training, but despite there having been no announcement to this effect, that appears to be exactly what happened. Beat writers haven’t tweeted about its use; no stories have been written about a rattled pitcher who had a ball called against him; league officials haven’t commented on it. The clock has largely faded from the rule change conversation since Passan’s report. But I was still curious whether it was really being used as intended, and what effect that might have on time of game.

From the beginning of spring training through March 10, I recorded the game time of every single game, with the exclusion of exhibition games that weren’t played between two major league clubs. In my 254-game sample, I found that the average spring training game lasted two hours and 57 minutes.

I completed this same exercise for spring training games from the beginning of spring training until March 10 last year, too, in order to see if there was any noticeable difference. But, nope, there was not. In my 242-game sample of 2018 spring training games, the average time of game was two hours and 57 minutes. Yes, exactly two hours and 57 minutes.

Perhaps MLB was enforcing the pitch clock during the early part of spring training before deciding to become more relaxed after negotiations on its use in the regular season were tabled. But if we compare the spring training time of game before and after it was reported that the pitch clock wouldn’t see major league action in the next two seasons, we see an insignificant difference, and one that doesn’t even go in the direction that we would expect. The 64 spring training games prior to Passan’s article lasted 177.2 minutes on average; the 190 spring training games that came after lasted 176.4 minutes on average. So it doesn’t seem likely that a difference in enforcement exists.

How much of a change would we have expected to see, had we been certain that the pitch clock was indeed enforced? Well, when baseball instituted a pitch clock in the upper minors, those leagues saw an average time of game difference ranging from between one to 15 minutes faster.

I would have loved to break these numbers down further, but unfortunately, public spring training data is relatively sparse. One interesting trend that I would have loved to consider is the possible pace difference between older, established big leaguers, and younger prospects who have been subjected to the pitch clock throughout their time in the upper minors. I’d bet that we would see that the younger pitchers throw at a brisker pace because of their existing familiarity with the clock, but alas, there isn’t enough out there to be able to distill it down in a rigorous way.

But, let’s get back to the essential question: is there enough evidence in game time alone to suggest that the pitch clock isn’t actually being reliably enforced?

Of course, because correlation doesn’t equal causation, we aren’t totally certain that the pitch clock hasn’t been enforced. Other factors do influence game time, such as the number of pitching changes, the length of commercial breaks, the pitches per plate appearance, and the runs scored per game. Any one of these factors could be significantly different than it had been, affecting the time of game, all while the pitch clock is being enforced. For example, the number of pitching changes could be way up in 2019, which would inherently also bring up the time of game. But the pitch clock could be counteracting this, resulting in the net zero in game time that we see.

Unfortunately, I could not consider all of these factors with the available data. I did, however, look at the overall run scoring environment. Through games played on Wednesday, the average team has scored 5.36 runs per spring training game in 2019, a slight increase from the 5.09 runs per game scored in 2018.

Would this 0.27 difference have a significant impact on game time? If so, we could then further test to see if that “net zero” theory I outlined above is true?

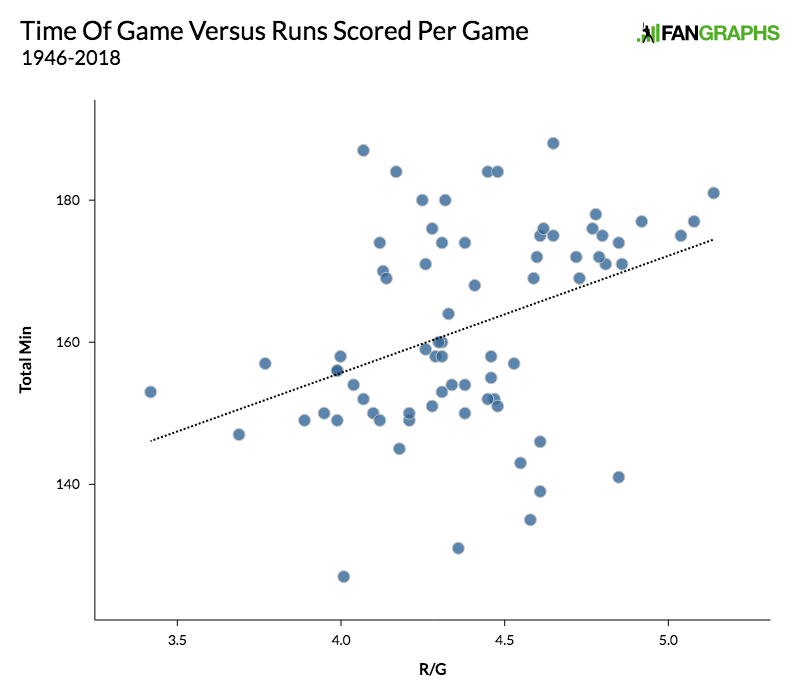

Looking at regular season baseball games played between 1946 and 2018 (the years with the most reliable game time data), we see that there’s only a moderate correlation between the number of runs scored per game and length of game.

Even still, if we assume that the 0.27 runs per game difference is making games longer, it would only be doing so by about four minutes. So, let’s say that spring training games should be four minutes longer in 2019 but the “enforcement” of the pitch clock is shaving those four minutes. If we are to run a hypothesis test at the alpha = 0.05 significance level using this information, we would actually find that there is statistical evidence suggesting that this would be a significant change. But does this mean that the pitch clock is being enforced? Maybe, but it is still not definitive.

Of course, this is operating under many assumptions. It assumes that the increase of 0.27 runs scored per game should be making each game four minutes longer; based on the weak correlation above, that’s far from a guarantee. This also still assumes that all of the other factors are being held constant, which is far from a guarantee.

To me, our best indication of game length and the effectiveness and enforcement of the pitch clock, are the two 2019 and 2018 game time figures I shared above, the figures that are both 177 minutes each. These figures tells us what we need to conclude that the pitch clock is probably not being enforced.

Devan Fink is a Contributor at FanGraphs. You can follow him on Twitter @DevanFink.

I recently attended three spring games in Arizona and the clock was not enforced. It started at 20 seconds when the pitcher received the ball and when it reached 4 or 5 seconds it was turned off. It did seem to me, however, that the pitchers were working a little faster than normal, perhaps to get used to the clock. Only once or twice, with runners on, did it pitchers go beyond 20 seconds.