The Rangers Are Winning the Framing Game

It feels like this season, umpires are under more scrutiny than ever before. Part of that might be because we’ve grown tired of the inconsistency that comes with human umpires, while another part could be access to more information, such as data on individual umpires’ accuracies.

On the sabermetric side, research on umpire performance has yielded mixed results. In April, our Ben Clemens examined whether the strike zone had changed and found no difference compared to previous seasons (though he noted that might not be very satisfying to frustrated fans). Recently, over at Baseball Prospectus, Rob Arthur concluded that the issue wasn’t the rate of wrong calls, but rather their magnitude. In other words, umpires are messing up in high-leverage situations. But is this because of umpires succumbing to pressure? Or just variance? The “why” component still eludes us.

In the midst of all the umpire-related hoopla, though, it seems like we’ve overlooked the importance of pitch framing. Until robot umpires come along, the art of presenting would-be balls as strikes (and making sure strikes don’t turn into balls) will remain relevant. This season’s umpires have been inconsistent, sure, but it’s undeniable that a certain amount of agency belongs to skillful catchers.

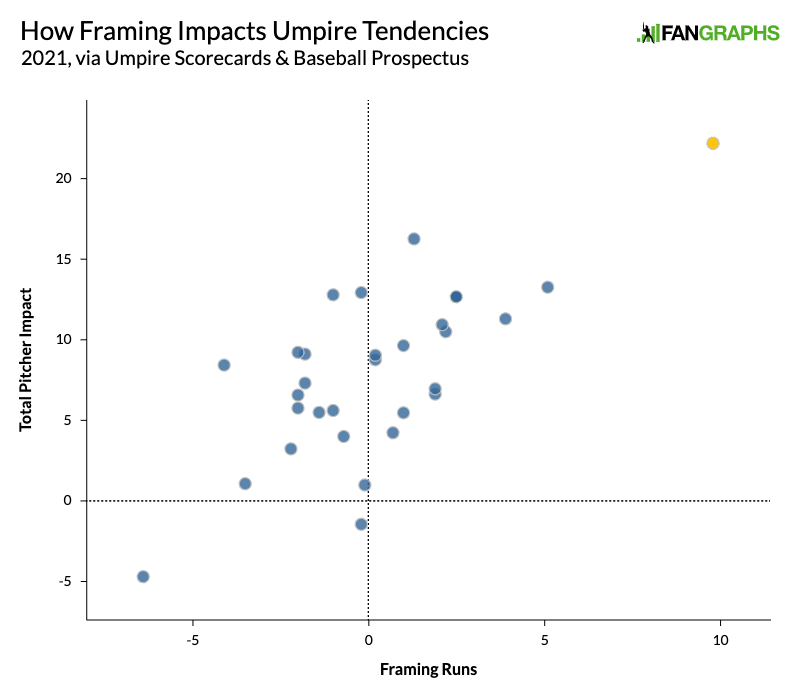

Yet, this article isn’t about the obvious standouts like Austin Hedges or Mike Zunino. Let me introduce you to a plot I constructed. On the revamped Umpire Scorecard website, I downloaded the ‘Total Pitcher Impact’ by team, which is “the sum of the run impact of each missed call when the team is pitching.” A positive sum indicates the pitching team benefited from the missed calls, and a negative sum indicates otherwise. Next, I consulted BP’s catcher framing leaderboards and figured out the total framing runs for each team. Is there any sort of relationship between the two metrics? Here’s what I found:

That’s pretty significant. There’s no one-to-one relationship between framing runs and umpire runs, but generally, teams with better catchers will receive the benefit of the doubt more often than not. It is worth noting that the correlation was weaker when I plugged in our own numbers, so take the results with a (tiny) grain of salt. Regardless, the point that framing matters remains.

But wait, see that tantalizing yellow dot in the upper-right corner? That’s right – the Texas Rangers are collectively on an island, benefiting the most from snatched calls. Specifically, Jonah Heim and Jose Trevino have been tearing up the framing leaderboards. Each site differs in how it calculates pitch framing, but they all agree that the Rangers’ duo is excellent:

| Player | FanGraphs | Prospectus | Savant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jonah Heim | 1st | 1st | 2nd |

| Jose Trevino | 10th | 3rd | 3rd |

As a prospect, Heim has garnered attention for his defense and an above-average hit tool. He can be found in the top halves of our site’s prospect lists, such as one from 2020 and another from a few weeks ago. Now, he’s a legitimate contributor to a major league team with a chance at longevity if his skills hold up. In Trevino’s case, he’s been on the Rangers’ big-league roster since 2019 in a backup role, but it’s only now that metrics have begun to depict him as an elite pitch framer.

This made me wonder – how exactly are Heim and Trevino framing pitches this season? What separates them from the remaining crop of catchers? The bad news is that pre-article, I knew a smattering on the subject. The good news, however, is that I reached out to Estee Rivera, a former college catcher and current baseball analyst, who kindly explained how catchers might set themselves up to frame an incoming pitch. What follows is thanks to him.

But first, to better analyze what constitutes good framing, we need to break down what constitutes bad framing. So here’s an example from a catcher who’s having a great season offensively, but not so much defensively (sorry Salvy):

The most glaring flaw is how low Perez snags the pitch, then drags it all the way up into the strike zone. His motion resembles one of those exercises where you raise a dumbbell towards your chest. That isn’t fooling anyone. Rather than stopping the path of the ball with a relaxed wrist, Perez submits to the movement of the pitch, making it appear lower than it actually is. With that in mind, consider how Trevino handles a sinker darting towards the bottom of the zone:

The pitch’s horizontal location is similar to that in the previous example, but how it’s received is not. Trevino’s wrist motion is faster and less exaggerated compared to Perez’s. And while he might have not received the call with a different umpire, it’s clear whose technique is smoother. How about a pitch that lands in the top of the zone? That would be harder to frame, but not impossible to pull off. With the count 3-1, Perez attempted to lower a Mike Minor fastball back into the zone. Let’s see how that went:

Yay, he did it! One problem, though: The process still isn’t ideal. The transition from receiving to framing is disjointed and therefore awkward, as if it’s obvious that Perez is trying to earn a strike. This isn’t entirely his fault because Minor misses the low-and-in spot, but the issue persists even when Perez sets up high. In contrast, here’s how Trevino dealt with a fastball:

That’s much quicker and better connected, with the glove clamping down in preparation for the frame job even before the pitch is fully secured. There’s stability in his wrist motion despite dealing with a 94 mph pitch. It’s a strike without any framing, but part of any catcher’s job is to make strikes even more convincing to eliminate doubt. But pitches aren’t just up or down; they’re also framed from the side. We’ve given plenty of spotlight to Trevino, so for a change, here Heim receiving an arm-side cutter from Kolby Allard:

Pitch framing is about how the catcher moves, but it’s also about how he doesn’t. Here, Heim seems to demonstrate his understanding of how Allard’s pitch behaves. He knows that its cutting action will bring it back into the zone, so rather than actively dragging the pitch, Heim lets it be, something a less erudite catcher might not realize. The broadcast’s zone will tell you the pitch is outside, but it’s arguably closer to a strike when taking its horizontal movement into account.

We know that Heim and Trevino are awesome at pitch framing, but how reliable are their results? It’s possible that they are benefiting from subpar umpires whose inaccuracies inflate the sort of framing metrics discussed so far. Back in 2015, Baseball Prospectus unveiled a new model to evaluate framing; within it, the authors also calculated how quickly Called Strike Above Average (CSAA) stabilized over the course of a season. The results are eye-opening: It took around just two months for the correlation between a catcher’s current CSAA and his final number to reach 0.90, a significant value.

In addition, I conducted an investigation of my own. Rather than look at in-season stabilization, I calculated the year-to-year correlation of catchers’ framing runs (FrmR), not CSAA. This process was repeated several times, increasing the required number of framing opportunities in increments of a thousands. By doing so, I similarly wanted to find a sample size at which the metric becomes stable. My methodology is far from perfect, but you can see the results here:

| Min. Chances | Sample | R-value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 91 | 0.49 |

| 1,000 | 61 | 0.51 |

| 2,000 | 48 | 0.54 |

| 3,000 | 32 | 0.50 |

| 4,000 | 22 | 0.58 |

| 5,000 | 15 | 0.61 |

There’s some statistical hijinks here, in that the fourth, more specific sample returned a lower r-value than the third one. Go figure! That’s likely due to the small sample size and noise baked into a metric like framing runs, such as count-dependency; successfully framing a pitch when it’s 0-and-2 is more valuable than when it’s 3-and-0, for example. So while CSAA stabilizes rather quickly, it’s possible that framing runs require an entire season’s worth of games. Perhaps it took a while for Heim and Trevino to emerge as two of the league’s best framers because of their lack of playing time prior to this season. Heim appeared in 13 games for Oakland last year, while Trevino contributed to just 53 games from 2019-20. It’s only now that their skills are translating to added runs.

In a similar vein, there’s nothing spectacular about this Rangers squad at a glance. But when it comes to influencing the outcome of a taken pitch? Right now, you can’t say they’re anything but the best.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

“Right now, you can’t say they’re anything but the best.”

The best at cheating. Framing is fraud. If umpires weren’t incompetent it would be irrelevant.

Can you please point to the rule that catchers are violating?

You sound like fun at parties.

Fooling the official is a standard practice in every sport, whether it’s a receiver trying to draw a pass interference call or a point guard trying to sell a foul at the rim. This is baseball’s version of that

Exactly — I will never understand the sentiment that this kind of thing must be eliminated by robot officials so that a *game* can meet somebody’s definition of ‘perfection’ — which is of course a fool’s errand because any robot will also come with its own irreducible variance.

Well, I don’t know, it’s a reasonable choice if the technology is feasible. It just doesn’t seem like it is.

As it stands, though, framing is fine.

Framing should be frowned on the same way flopping is frowned on in other sports. In baseball, deceiving the umps is praised while fans of other sports typically despise flopping except when it helps their team.

While framing and flopping are both attempts to work the refs, they are fundamentally different in-game actions.

Flopping is objectionable because the flopper abandons his usual duties (e.g., offensive player falls down in exaggerated agony rather than trying to actually score a goal) in an effort to get a call that disrupts the action. A framing catcher is doing precisely his duty, catching the ball, and his intention is not to disrupt the action for the sake of some ‘penalty’ reward.

Quite frankly, flopping speaks to an inelegance in the rules of soccer (and to a lesser extent, basketball — lesser only because in basketball it is the defense that has more incentivize to flop). Baseball doesn’t have that problem.

Framing causes catchers to miss catching balls (good framers usually have more wild pitches go by and passed balls). Based on your criteria of abandoning duties being the difference between framing and flopping and catching the ball being listed as the primary responsibility of the catcher, flopping and framing are similarly repugnant.

If framing *required* dropping the ball, as flopping requires falling down, then you’d have a point.

If flopping “required” the player not to try to make a play, then you would have a point. James Harden still makes layups while flopping. Catchers still catch balls while framing. They are both preforming unnatural acts going for the deception over just doing their primary function.

Trying to sell a foul while making a layup is not flopping. Catching a ball a certain way, even if some less-skilled catchers have more trouble catching that way, is not flopping. Falling down in fake agony instead of trying to score a goal is flopping.

The requirement of not trying to make the play is right there in the term: ‘flopping’.

Are you really claiming that, in the gif’d examples of good framing that are embedded in this article, there are ‘unnatural acts’ being committed? And would the solution to these ‘unnatural acts’ really be the installation of robots?

What exactly would you like the catcher to do then on a borderline pitch? Why would he not move his glove in the direction of the strike zone?

“Framing causes catchers to miss catching balls (good framers usually have more wild pitches go by and passed balls).”

Where’s your evidence?

I’d also love to see numbers on this, Joe Joe. It’s an interesting idea, and I could see the data bearing it out! But until I see that info I’ll be merely intrigued

All framing really is is presenting the ball in a way that makes it easier for the umpire to call the ball correctly. How is this cheating? Bad framing is incompetence!

Nah those two awesome catchers are the best of taking advantage of crappy umps!

Pitch framing – the art of using ump incompetency as a weapon

how is minimizing an UMPS mistakes against your team cheating! All humans make mistakes. If a catcher can minimize bad calls against his pitchers he should be applauded.

I wouldn’t call an umpire “incompetent” for making a different call, 5% of the time, than a robot that also has finite precision.

The differences between robots and human umpires are 1) some degree of precision, although this is hard to quantify without consulting an even more precise robot, and 2) sensitivity to things like framing and game situation.

I think the game is better *with* those sensitivities, which are worth sacrificing some degree of precision.