“The Thing” About Alex Cobb’s Almost No-Hitter

Late on Tuesday night, baseball fans all over the world tuned their dials to the ninth inning of the Giants and Reds’ matchup in San Francisco. Through eight innings and 25 batters, Giants starter Alex Cobb had allowed just a single baserunner on a Casey Schmitt error, while setting down the other 24 in order. In the ninth, Cobb sandwiched a walk between two routine fly outs before leaving a splitter over the heart of the plate to Spencer Steer, who crushed an opposite-field liner past the outstretched glove of right fielder Luis Matos to end the no-hitter and the shutout. While a splitter ended Cobb’s no-hit bid tantalizingly close to completion, it’s also the reason his attempt got that far in the first place. Even independent of Cobb’s brilliant outing, his splitter made history in its own way on Tuesday night.

Before going into the splitter, let’s talk about Cobb’s general approach to pitching. He’ll try to catch you off guard with a knuckle curveball on the first pitch, hoping to steal strike one (nine of the 11 curveballs in his complete game were on first pitches), but after that he almost exclusively throws sinkers and splitters in near-equal proportion. These two pitches operate similarly – both leverage the power of seam-shifted wake to maximize arm-side movement, missing barrels and getting batters to hammer the ball into the ground when they make contact. But a quick look at the plate discipline metrics shows his distinct goals in utilizing each pitch:

| Pitch Type | Velocity | IVB | Vertical Drop | Horizontal Break | Zone Rate | Called Strike% | Swinging Strike% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinker | 94.6 mph | 6.9 in | 23.7 in | 15.9 in | 56% | 26.4% | 5.2% |

| Splitter | 89.6 mph | 2.1 in | 32.1 in | 13.1 in | 37.4% | 6.2% | 14.4% |

Like many pitchers who throw splitters, Cobb uses his as a weapon to get hitters to chase below the zone. He’ll get hitters into uncomfortable counts by filling the zone with sinkers, then throw a split that looks nearly identical before diving beneath their barrels. Splitters are pretty uncommon in the majors – while 2023 has represented a peak in splitter usage, they still only represent about 2% of total pitches. While there are others who throw splitters, including Kevin Gausman, Taijuan Walker, and most notably former NPB players like Shohei Ohtani, Kodai Senga, and Shintaro Fujinami, what separates Cobb from the rest of the pack is the sheer frequency with which he throws them. In the past three seasons, he’s ranked first, first, and second in splitter usage rate among starting pitchers, throwing them 38% of the time this year. This splitter, dubbed “The Thing,” ranks second among splitters to Gausman’s in pitch value since Cobb’s debut in 2011. The Thing isn’t just Cobb’s main secondary pitch, it becomes his only secondary pitch in deep counts. And sometimes, he’ll make it his primary pitch.

Cobb threw 83 splitters on Tuesday. Since the pitch tracking era began in 2008, no one else had ever thrown 80 splitters in a single game. Or 70, for that matter. Heck, besides a lone Brad Penny start in 2010 with 66 splitters, no one else had even thrown 60. Cobb’s shattering of the single-game splitter record wasn’t just a result of his pitch count (his 131 pitches thrown is the highest since Mike Fiers‘ no-hitter in 2019); he ranks behind only Penny in single-game splitter percentage, as they comprised 63.4% of his total offerings. Even throwing 50% splitters in a game is a rare occurrence, though it’s unsurprising to see Cobb dominating that leaderboard as well. In fact, all nine of his majority-splitter games have come in the past two seasons:

| Name | # of Games |

|---|---|

| Alex Cobb | 9 |

| Keaton Winn | 4 |

| Kevin Gausman | 3 |

| Brad Penny | 2 |

| Jose Valverde | 1 |

| Taijuan Walker | 1 |

| Shohei Ohtani | 1 |

Cobb’s splitter-first approach in this game offered many advantages over his typical plan of attack, which involves using sinkers to set up the splitter. The first – and most obvious – can be seen from a quick glance at his splits (no pun intended). His splitter is a darned effective pitch, leading his arsenal in chases, swinging strikes, ground balls, wOBA against, and overall run value. If you have a pitch that can do almost everything well, why not throw more of them?

Second, this change in pitch usage was likely a result of advance scouting on the Giants’ part. While the Reds’ offense is middle of the pack versus sinkers, they rank 13th in the NL in wOBA against offspeed pitches. One hitter who particularly struggles against offspeed stuff is TJ Friedl, hitting just .167 with a 34% whiff rate. Cobb capitalized on this weakness by throwing him 11 splitters compared to just four sinkers, three of which came on his first pitches of the game. Friedl’s 0-fer brought his line against splitters to a measly 1-for-19. Reds hitters swung and missed 18 times in their effort to muster up one hit, a season high for Cobb. Unsurprisingly, all 18 whiffs came against The Thing.

Finally, scaling back the sinker in favor of the split has made the sinker even more effective, especially in taking free strikes when hitters were expecting a splitter to dive beneath the strike zone. While Cobb’s surface-level results have been shockingly consistent in the past three years, posting ERAs in the mid-threes, he’s experienced extreme levels of variance under the hood. After posting an impressive 2.80 FIP and 3.15 xERA in his debut season with the Giants, his FIP has climbed by a full run and his xERA has jumped to a scary 4.64. While he’s earning fewer whiffs than before, the most noticeable difference from last year is a near doubling of his home run rate. While it’s easy to point to an outlier HR/FB rate and claim bad luck, his barrel rate has spiked at a rate proportional to the increase in dingers.

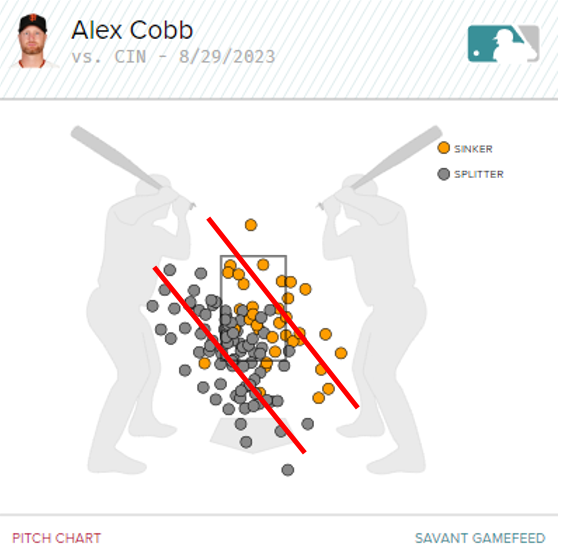

The sinker has regressed the most, allowing nine homers so far (compared to just four last year) and a .365 xwOBA, the highest of any of his pitches. On average, he’s thrown his sinkers higher than any other season in his career, preventing it from working its magic as a groundball pitch. And while a difference of a couple inches may not seem significant, just a few mistake pitches can have an outsized effect on barrel and home run rates. Indeed, his sinker’s Location+ has fallen from 105 to 102 over the past two seasons, as higher sinkers tend to be hit harder and on a line. In this start, he missed spots with both pitches along his arm’s path through the zone, but his ability to draw chases on low splitters kept him out of dangerous hitters’ counts:

If hitters are doing more damage to the sinker than they used to, then it’s in Cobb’s interest to get as few swings as possible against it. This is where the splitter comes in. Batters thinking of the splitter as the primary pitch may give up on offerings that they expect to move out of the zone, instead watching them flutter over the plate, even when located suboptimally. In the seventh inning, both Steer and Elly De La Cruz took first-pitch sinkers in the nitro zone, setting the table for a barrage of splitters chased outside the zone that led to a strikeout and groundout. Of Cobb’s 36 sinkers thrown, 17 were taken for strikes, giving him the upper hand in countless plate appearances. While the average hitter swings at about two-thirds of the pitches they see in the zone, Reds hitters saw 23 in-zone sinkers and swung at just six of them. Even when they did swing, none of the balls put in play against it had an xBA higher than .200. In total, Cobb racked up 28 called strikes on the night, tied for the second most of any pitching performance all year.

Leading with the splitter allowed Cobb to maximize the strengths of his wipeout pitch, while simultaneously shielding the weaknesses of his sinker. The synergy of his arsenal, along with added velocity, has brought Cobb to a new career apex at an age when many pitchers are in decline. And he’s doing this despite recovering from two major injuries and temporarily losing feel for his signature pitch. Yet, his 3.20 FIP over the past three seasons is the best stretch of his career, and he’s recently added his first All-Star appearance to the mix. Losing a no-hitter just two strikes away from glory can be heartbreaking, but he’s only come back stronger from adversity before. That’s just The Thing about Alex Cobb.

Kyle is a FanGraphs contributor who likes to write about unique players who aren't superstars. He likes multipositional catchers, dislikes fastballs, and wants to see the return of the 100-inning reliever. He's currently a college student studying math education, and wants to apply that experience to his writing by making sabermetrics more accessible to learn about. Previously, he's written for PitcherList using pitch data to bring analytical insight to pitcher GIFs and on his personal blog about the Angels.

Splitter szn