Victor Scott II Has Stepped Up

Last year, Victor Scott II broke camp with the Cardinals behind an avalanche of buzz. He’d swiped 94 bags in the minors the previous year while playing elite defense in center field and posting a solid batting line. With the new rules providing a tailwind to speedsters, Scott seemed like the next exciting Cardinals position player. But then he hit the major leagues, or rather, didn’t hit in the major leagues. He batted .179/.219/.283 over 50 games of action and ended up down in Triple-A, a level he’d skipped during his meteoric rise, where he also struggled.

This year, Scott is back in the majors, but with considerably less hype surrounding him. However, a month into the season, he looks like a completely different hitter. He’s walking more, striking out less, and hitting for a higher average thanks to more line drives. He’s also living up to his potential on the basepaths and in the field, with a perfect 9-for-9 stolen base record and good defense. Last year’s version of Scott? Unplayable. This year? A fun upgrade on Kevin Kiermaier. Could the new version possibly be here to stay? I dug into the numbers to hazard a guess.

The main thing I’m interested in when it comes to Scott is how he gets on base. That’s what makes him intriguing – once he’s on first, he’s basically on second. Since you can’t steal first, that’s where the pinch point is. And in 2024, pitchers had a simple plan: Attack the zone and dare Scott to do anything about it. That helps explain his 3.9% walk rate – he got to a 1-0 count in about a third of his plate appearances last year. Similarly, he reached two or more balls in a count only about a third of the time.

There are major league players who succeed despite working from behind in the count so frequently, but they tend to have an elite compensatory skill. I’m talking about Luis Arraez’s contact, Jake Burger’s power, Bo Bichette’s feel to hit. Honestly, most hitters who get ahead in the count and walk so rarely just aren’t good. Pitchers don’t let them get into advantageous counts; the group is dotted with low-power defensive specialists who pitchers simply don’t respect.

So far in 2025, these trends have changed massively for Scott. He’s getting ahead in the count 1-0 about half the time, and also getting to two or more balls at a 50% clip. In both metrics, he’s as far above average as he was below average last year; this is the territory of LaMonte Wade Jr., Lars Nootbaar, and Justin Turner. This central change has completely altered Scott’s game. He’s walking twice as often and striking out less. More than half the time that he puts the ball in play, he’s doing so while ahead in the count, a huge increase from last year. If he can keep this particular change up, I almost don’t need to look at the rest of his game; some OBP plus his speed and defense is all he needs to be a valuable player.

Clearly, when it comes to batters getting ahead in the count more frequently than they had previously, pitchers have to cooperate at least a little bit, and that’s been the case with Scott so far this year. Instead of daring him to hit it, pitchers are nibbling:

| Year | 0-0 Zone% | 0-0 Heart% | Pitcher Ahead, Zone% | Pitcher Ahead, Heart% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 57.1% | 32.1% | 42.2% | 21.1% |

| 2025 | 42.0% | 23.0% | 25.0% | 12.5% |

When they got ahead in the count last year, pitchers hammered Scott mercilessly. That 21.1% heart rate is downright disrespectful. On the other hand, his 12.5% mark this year is unrealistically low; only one player in baseball saw middle-middle pitches less frequently when behind in the count last year, and that was Javier Báez, who pitchers avoid not because they’re afraid of him but because they know he’ll swing at pitches outside the zone.

Ah, but does that mean Scott doesn’t have anything to do with his improvement? Is it all just pitchers incorrectly staying away from him? I don’t think so. He’s remade his game in an interesting way, and so far it seems to be paying dividends. I’m not saying that pitchers are right to avoid him to this degree, and I expect that he’ll face more in-zone attacks as time goes on. The good news is he’s already made a change that has helped him when he sees those in-zone pitches.

What should you do when you see a fastball in the strike zone? Mash it, particularly if you see it with fewer than two strikes. That’s the best time to attack. Scott did just that in 2024, posting a 69.7-mph average swing speed, 0.6 mph faster than his average swing. This sounds logical – he swung hardest when he was facing hittable pitches and a whiff wouldn’t end the count. Paradoxically, in 2025 Scott’s swing speed on these before-two-strikes fastballs has declined by 2.5 mph. But it gets weirder; he’s hitting them better than ever:

| Year | Swing Speed | Hard Hit% | Barrel% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 69.7 mph | 43.9% | 7.3% |

| 2025 | 67.2 mph | 41.2% | 11.8% |

This doesn’t sound particularly sustainable, and to be honest, it’s probably not sustainable quite the way he’s doing it. His contact quality is going to decline — no one runs a 26.2% line drive rate forever — and he certainly isn’t going to keep swinging softer while hitting more barrels. The notable thing here, though, is that Scott is hitting the ball in the air more often against fastballs. Last year, despite being a fly ball hitter overall, he couldn’t lift heaters. His 44% groundball rate against fastballs was higher than the league average. Instead, his fly balls came against secondary stuff.

Ask any hitting coach: The whole “elevate and celebrate” trend is largely about tagging fastballs, not sliders. Hitters make a living spitting on breaking balls and punishing fastballs. Scott was pounding fastballs into the ground while getting under changeups and breaking balls. It’s the opposite of what you want. Last season, Scott made hard contact on 16% of his swings against fastballs, compared to only 6.3% of his swings against secondaries. That trend has held so far in 2025, with Scott hitting the ball hard on 14.3% of his swings against heaters and on 4.6% against secondary pitches. But he seems to have realized that putting that weak contact in the air wasn’t working for him. Now, he’s having more success against the hard stuff because he’s punching it in the air.

You might think that Scott’s profile argues for grounders instead of fly balls. After all, a lefty who might be the fastest man in baseball can get down the line pretty quickly to beat out infield singles. But all I can tell you is that the numbers don’t bear that out. When Scott puts the ball on the ground, he has a .208 BABIP and essentially no power. When he puts the ball in the air, he’s batting .354 (.323 BABIP, sac flies are weird) with extra-base pop. Now, it’s not homer power, but with Scott’s speed, doubles come easily:

Sure, that one was a fluke. But Scott’s speed creates flukes. You can’t play the infield back against him; he’s too fast. And that speed adds bases left and right. Very few batters make it to second on that bloop up above. And watch this one:

Almost everyone else would settle for a single here. The angles just work differently with Scott, and that’s where most of his damage-on-contact gains will be made. Considering he’s in the 13th percentile for average exit velocity, he doesn’t have the physicality to be a 20-homer guy — that’s OK. Scott rarely hits the stuffing out of the ball, so adding a mile an hour to all of his batted balls would do very little. But what about putting more of those batted balls in the air, where they can find seams in the outfield grass or bloop over infielders? That’s how he can juice his results on contact.

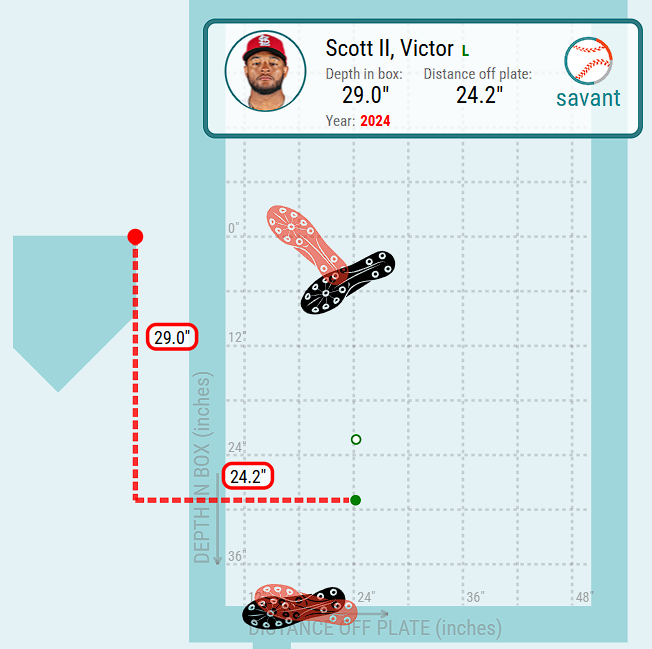

Scott has made another canny adjustment that’s working in concert with this one. He’s stepped up in the batter’s box meaningfully and changed his stance. Baseball Savant’s new stance tracking provides a great visual. Here’s 2024:

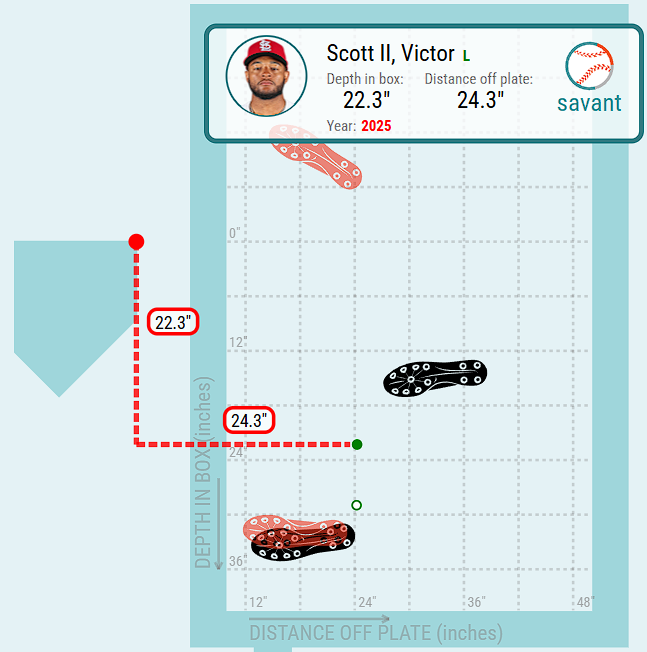

And 2025:

He’s now standing seven inches closer to the pitcher. That explains part of Scott’s slower swing speed – his swing length is shorter because he’s meeting the ball earlier. It also explains a huge change in his batted ball tendencies; he’s going to the opposite field more often, and he’s connecting with the bottom part of the ball more frequently because he’s making contact earlier in his upward swing path. Last year, he sent his elevated contact to the opposite field 32% of the time. That rate is up to 46.5% this year, and he’s even sending more of his grounders to the left side of the mound as well. That’s yet another useful improvement for someone with his speed.

You’ve heard about the pulled fly ball revolution for over a decade now, but Scott’s trying something different. He’s not capable of using a lift-and-pull hack to get to 15 homers; he topped out at nine in the minors, and I doubt it’s going to be easier for him to go yard against big league competition. But by changing where he stands, he’s changed the equation. He’s now hitting the ball hard 20% of the time that he goes the other way in the air, up from 10% before. That follows from the mechanics; he’s meeting the ball earlier when his timing is right, thanks to standing closer to the mound. That means that he’s sending it to left field with authority more often than last year, and he hasn’t sacrificed much pop to the pull side either. At this point, when he pulls a ball, it’s because he saw it perfectly and got the bat head out early, so while he’s rarely sending the ball to right field, his expected (and actual) results on pulled fly balls haven’t worsened even with the new stance.

In essence, this is what’s beguiling pitchers: It’s much harder to overpower Scott in the strike zone. Instead of just hacking away with bottom-tier contact quality, he’s made a big adjustment to what he’s trying to do. He’s not just another cookie cutter hitter with worse power; he’s forcing the issue by crowding closer, trying to punch fastballs the other way and get to secondary pitches before they break.

I don’t think pitchers will continue to avoid Scott like they have. He can’t punish them enough for them to be afraid of him; even with his new and improved approach, he has a substandard .112 ISO. Those gapped line drive doubles are an improvement from 2024, but they don’t make up for all the homers that your average major leaguer can hit that Scott can’t. There’s no reason to be staying away from this guy as much as the league has done so far this year. As such, I’m expecting his walk rate to creep down as the season progresses.

Even so, just because the early-season results look unsustainable doesn’t mean that Scott’s plan is bad. In fact, I think what he’s doing is brilliant. He doesn’t need to be the next undersized batter who maximizes his power potential by pulling fly balls for homers. If he can be merely a below-average offensive player with on-base skills, he might be a borderline All-Star because his defensive and baserunning skills are just that good. And if he can be stay right around league average at the plate, he probably will be an All-Star. So next time you watch Scott, keep an eye on left center field. If the start to this year is any indication, that’s the area where he does his best work.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Great article. The stance charting is interesting and I look forward to seeing comparisons for other hitters who’ve changed their approach.

Agreed, seeing those charts is really cool! I feel like we, the general public, used to mainly have gifs from the standard camera angle to judge stance changes, which is really hard to get a read from. It’s a lot easier to see the change with these.

Thanks Ben for another good one!