Welcome Back, Robbie Ray

Back in the halcyon days of 2021, things were looking up for Robbie Ray. After a promising but inconsistent start to his career, he put everything together all at once and won a Cy Young award. He hit free agency on the back of that season and signed a deal that guaranteed him five times what he’d made in the majors so far. The future was bright – except that Ray turned around and put up a miserable 2022 campaign, meaningfully worse across the board despite pitching in Seattle, where trained squirrels can go six innings and give up two runs in the pitcher-friendliest ballpark in the big leagues. Then he got hurt. And later got traded as salary ballast. Life comes at you fast.

Ray would hardly be the first pitcher to spike some hardware in a weak year — only six AL pitchers reached 4 WAR in 2021; Ray wasn’t one of them — and then fade away. Rick Porcello says hi, by the way. If Ray’s last act was keeping replacement-level time on the Giants, at least he got his one big payday. Expectations weren’t high, and when he was shut down with an injury only a month after returning in the second half of last year, they fell further still.

Of course, I’m writing this article, so you know that hasn’t continued. Rather than teeter into irrelevance, Ray has come out strong to start 2025. He looks as good as he has since his award-winning season – and arguably even better. So let’s look at how he’s doing it now, because whether you’re a long-time Ray-head or just seeing the first Rays of light this year, he’s a strange enough – and fun enough – pitcher to be worth taking notice of.

The one-phrase hook for Ray isn’t an exciting one. “Fastball-dominant, best pitch by far, sits 93-94.” Right, yes, into the fifth starter pile — we have a lot of résumés to look at today. But it’s not nearly as dire as that sounds. Ray’s medium-velocity fastball is actually incredible. Like, PitchingBot thinks it’s better than the incredible four-seamers of both Zack Wheeler and Jacob deGrom. Stuff+ agrees.

Results agree, too. During his lengthy career, Ray’s overall arsenal has been worth 26.3 runs above average. If you assign a run value to every pitch he’s ever thrown – looking at the difference between the game state before and after every single offering – his fastball has been 59.7 runs above average. Everything else he’s thrown has cost him runs, a collective 33.4 of them. When I say that Ray is fastball-dominant, it’s a compliment. He really, truly does have a dominant fastball, the kind that few players in baseball possess these days.

We usually reserve the verb “bully” for the very hardest throwers. Mason Miller bullies people with his fastball. So did Aroldis Chapman at his peak. Ray bullies hitters too, though, and he doesn’t even need velo to do it.

This swing had no chance:

Nick Castellanos was late and low here:

Lefties look downright foolish against the pitch:

The secret to Ray’s fastball is backspin. It’s something we’ve long known about four-seamers; the more you spin them, the better they perform. Ray generates a huge amount of ride thanks to an over-the-top arm angle and plenty of spin. Ray makes it play up even more by keeping the ball up in the zone, where the shape leaves hitters flailing at unhittable missiles. The trajectory of his fastball is something you’d cook up in a lab.

One thing you wouldn’t cook up in a lab? The rest of Ray’s arsenal. See, the all-backspin plan has a weakness: Ray can’t help but backspin everything. His slider is an odd duck, a gyro slider that he throws in the upper 80s. The odd part about it? He backspins it. Again, he can’t seem to stop himself from doing it. Here’s a list of all the sliders in baseball that have as much induced vertical break as Ray’s:

| Pitcher | Sliders | MPH | IVB (in) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyler Rogers | 86 | 73.7 | 15.3 |

| Robbie Ray | 244 | 87.9 | 9.6 |

Uh, yeah, that’s not a reasonable comp. The only guy whose slider sits up more than Ray’s is literally throwing underhand. Many pitchers throw some version of Ray’s rising slider, but few of them induce so much vertical movement – and none of them induce that kind of break without huge two-plane action. Ray’s slider barely moves in the horizontal direction relative to its initial trajectory. No one within three inches of him in terms of vertical break has less than four inches of glove-side movement. Ray’s slider is barely a slider, in other words. It’s more of a powered-down cutter.

Our pitch models hate this pitch. You can see why – it does nothing that a slider is supposed to do, and instead does a thing that you don’t want your sliders to do. It works OK as a strike-stealer, because hitters expect more drop and take it at the bottom of the zone:

It works much less well over the middle of the plate:

I can’t wrap my head around that being a good pitch. To Ray’s credit, he knows where it’s at its best – with two strikes against lefty hitters – and uses it as often as he can there. He throws it to righties only as a strike-stealer, and when he does challenge them in the zone, the results have been poor. It’s the kind of slider that no one would choose – but if you throw a fastball that’s as good as the one Ray does, you might be willing to live with a strangely shaped secondary pitch.

Wait, did I say a strangely shaped secondary pitch? Strangely shaped pitches, plural, would be more accurate. Because let me tell you about Ray’s curveball, a pitch he’s thrown around 10% of the time this year. His curveball isn’t quite as extreme as his slider, but it drops less than 85% of all curveballs, and out of every single curve in baseball, only Mitchell Parker’s gets less glove-side movement. Like his slider, Ray’s curveball is mostly straight up and down thanks to his natural pitching motion, a backspin-heavy fastball delivery. That’s why he spikes his curve: to generate downward movement despite his natural grip. And lest you think this is some small-sample issue with only 100 curveballs thrown in 2025, Ray has actually added a meaningful amount of drop to the pitch – nearly five inches – since his Cy Young season. It used to have even less movement.

That makes it less of a curveball and more of a rainbow. That’s worked out about as well as you’d expect – he’s barely missing any bats, opponents are almost never chasing it, and when they do swing, they’re making contact at a huge clip and lacing line drives. Our models also hate this pitch, and I can see why. Even when it works, it never looks like it should:

That’s the best way to use a lollipop curve with little bite: as an occasional early-count strike-stealer. Since Ray is often pitching backwards to get his strikeouts, firing four-seamers in two-strike counts, he likes to mix things up early on even with his less exciting offerings. But there’s a limit to how often you can do that, of course, and Ray is approaching that limit; 40% of the curveballs he’s thrown this year have started plate appearances. That’s one of the highest marks in baseball, and the guys who use it more than him all throw significantly bendier curveballs.

As a Giant in 2025, Ray has also been experimenting with his pitch mix. His slider is so bad against righties that he’d prefer to throw them only fastballs. But of course, that doesn’t usually work, so he’s added a new pitch: a changeup that he invented this winter. It’s 5 mph slower than the last iteration of an offspeed pitch that he tried, back in 2021. And you’re never going to believe it, but he produces a ton of induced vertical break by backspinning it. Here is another list, this one of the changeups with at least as much induced vertical break as the one Ray throws:

| Pitcher | Changeups | MPH | IVB (in) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyler Anderson | 291 | 78.1 | 12.9 |

| Robbie Ray | 114 | 84.8 | 11.8 |

Huh, yeah, this guy really can’t do anything but produce backspin. It’s not a completely disastrous outcome for a changeup, because most of a typical changeup’s value comes from deception and separation from the four-seamer — and as we already know, Ray’s fastball rises a ton — but it’s dangerous to leave a changeup with that shape in the zone. Yet again, our models think that it’s a poor pitch measured by stuff; to make it work, Ray has to locate it well. This play worked out, but it’s easy to see how it might not have.

It probably sounds like I’m trashing Ray. After all, we’ve talked about four of his pitches, and three of them are, to be kind, subpar. The same skills that make him so good at throwing a fastball make it hard for him to manipulate breaking balls and changeups the way he’d like to. But Ray has found a solution: He just walks more guys.

In his Cy Young season with the Blue Jays, Ray attacked the strike zone with reckless abandon, posting a career-low walk rate. He also allowed a ton of homers, more per nine innings than in any previous full season. That’s because his arsenal isn’t well set up to attack when he’s behind in the count; none of his secondaries play all that well in the zone, and hitters are trying to mash fastballs when they’re ahead.

Here’s one way of thinking about it: When he fell behind 1-0 that year, he walked 12% of the batters he faced. This year, that number has ballooned to 20.4%. He’s fallen behind 2-0 against 32 batters this season – and walked 12 of them, a rate of nearly 40%. On the other hand, he allowed a .400 slug after falling behind 1-0 in 2021. That’s down to .321 this year. That’s the trade-off. Ray’s arsenal works a lot better when he’s ahead, and he’s just picking his poison when it comes to a behind-in-the-count plan.

You know what’s wild? It all works. Ray is so good when he’s ahead that all those extra walks don’t matter. He’s shutting down guys when he gets a strike on the first pitch of the at-bat, with a 36% strikeout rate that’s actually below his career average. He’s lethal with that fastball when he gets to two strikes. The only pitchers with a higher putaway rate – percentage of two-strike fastballs that turn into strikeouts – are Wheeler, Hunter Brown, Nick Pivetta, Joe Ryan, Kris Bubic, Tarik Skubal, and Garrett Crochet. That’s five of the top 10 pitchers by WAR this season, and another two in the top 25. In other words, better company does not exist.

Even Ray’s secondary offerings work well with two strikes. “But Ben,” you might say, “didn’t you say these secondaries were bad?” Well, sure, but with two strikes, the game is different. He’s still in the 65th percentile, better than league average, when it comes to converting those pitches into strikeouts. That’s because hitters are trying to sit on fastballs and then react to secondaries, which makes it easier for him to leave the strike zone and still draw chases. Sure, the lazy curveball isn’t a great two-strike pitch, but if you’re gearing up to hit Ray’s impossible four-seamer and he drops a slider, it matters less that the slider is shaped weird and more that you’re pinwheeling around trying to hit a pitch that didn’t get thrown.

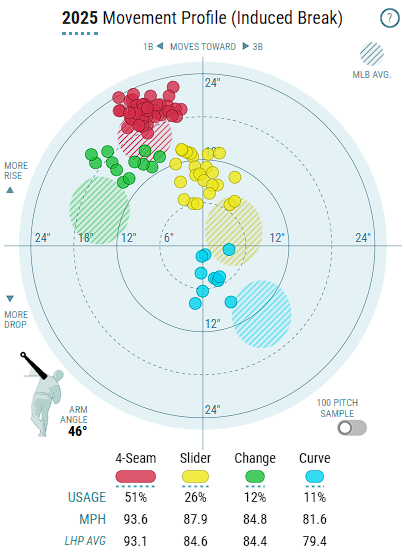

This is all a long-winded way of saying that I absolutely love watching Ray pitch, and you should too. He’s so weird! He’s a man who lives by the fastball in a time when almost no one does that. He’s like a Zack Wheeler starter kit, only with half of the pieces missing. Look at how strange his movement profile is relative to the league average (the shaded areas, courtesy of Statcast):

It would be one thing if this plan resulted in a replacement-level starter. That doesn’t sound so outlandish; one good pitch plus some areas for improvement gets plenty of people to the majors. But Ray is thriving. He’s probably not going to keep up his 2.67 ERA, but his 3.22 xERA and 3.48 FIP suggest that he’s doing something right. In spacious Oracle Park, and with Ray mainly challenging righties with fastballs or ducking the zone with changeups, I think he’s unlikely to give up a ton of homers.

It really shouldn’t work. In the long run, maybe it won’t. Ray is 33 and coming off two straight shortened seasons. If his fastball was merely good instead of great, he’d never survive. But right now, it’s great, and he’s built a completely unique set of pitches behind it. That, more than the occasional walk, and a friendly home stadium have turned Ray into one of the Giants’ best pitchers – and as they cross the quarter mark of the season in playoff position, he’s an integral part of their resurgence. Just don’t let him fall behind in the count and throw a changeup.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Great article, Ben.

Obviously not everyone can do it, but I really think Ray should try picking up a splitter. For a guy who can only get backspin on everything, why not go with a pitch that you can throw with the same spin axis as your fastball and just kill the spin rate with your grip?

That would be cool! How about more fastballs too? If he’s good at throwing one, would that translate to throwing other types like sinker/2seam or cutter?