What Makes Freddie Freeman Special, in One At-Bat

Freddie Freeman has dominated the sport for over a decade. It feels impossible to summarize his well-rounded skillset with any single plate appearance, but I think I’ve found one. Last Monday, in the ninth inning of a Dodgers loss against San Diego, Freeman stepped into the box against Josh Hader and in the span of eight pitches demonstrated what makes his talent so special.

Freeman is the MVP candidate, but Hader is no slouch either. Since debuting in 2017, he leads all relievers in WAR, ERA, and strikeout rate. The first part of this at-bat is all about him, as he immediately claimed strike one with a sinker:

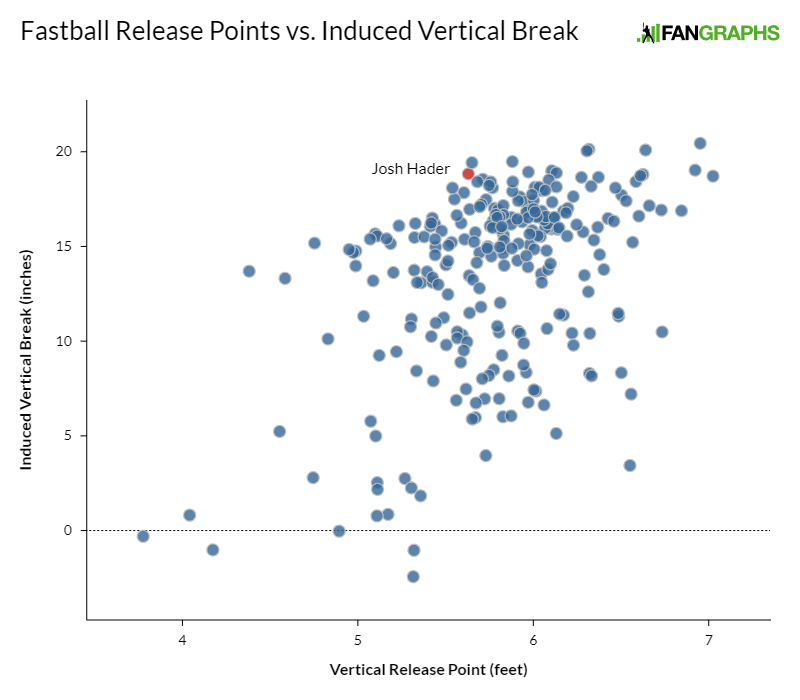

Statcast registered this pitch a tad below the strike zone (though it was closer than the broadcast strike zone would indicate), but Hader got the call anyway. Catcher Luis Campusano grades out poorly overall as a pitch framer, though the region right below the zone is one of the few areas where he helps his pitchers earn strikes at an above-average clip. Another factor working in Hader’s favor is his 97th-percentile vertical approach angle, as flatter pitches tend to rack up called strikes. While most pitchers try to maximize drop on their sinkers, Hader’s pitch behaves much more like a four-seam fastball; with plus vertical carry and his tendency to throw up in the zone, it displays all the properties of a four-seamer except for the two-seam grip. Per Alex Chamberlain’s pitch comparison tool, each of the 90 most comparable pitches to Hader’s sinker are four-seamers. But no matter how we classify it, Hader’s ability to generate vertical break from such a low release point is nearly unparalleled.

High-octane closers don’t dominate the strikeout leaderboards by making hitters watch balls go by; they use their stuff to rack up whiffs. On the second pitch of this matchup, Hader made Freeman look bad with another sinker:

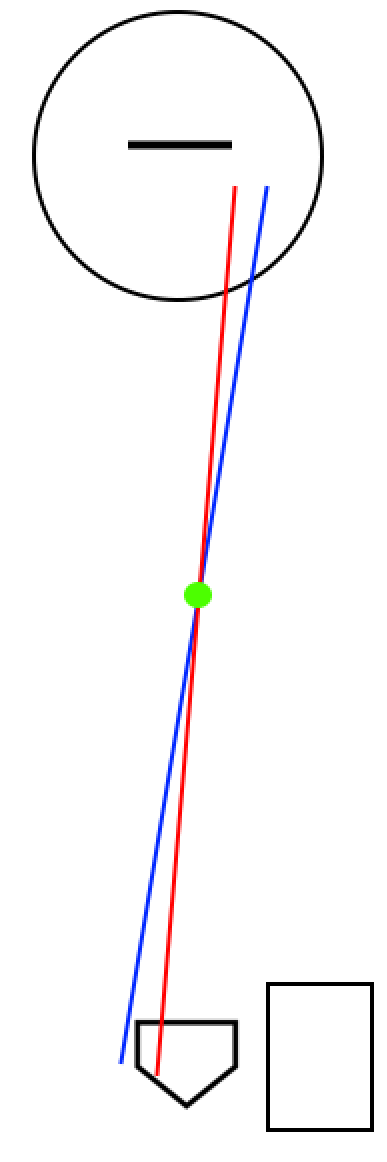

All elevated flat fastballs are difficult to make contact with, but especially when they’re buzzing in at 97 mph from the left side. But Hader’s fastball has yet another property that makes it so lethal. As a consequence of his low-slot delivery, he releases the ball far to the first base side of the mound, giving him an outlier release point in both the vertical and horizontal directions; his 95th-percentile horizontal approach angle puts him in the company of true sidearmers like Aaron Loup and Jake Diekman. Horizontal approach is why this pitch, thrown to Hader’s glove side, can be a whiff machine. Consider this (not to scale) birds-eye view of the trajectories of Hader’s fastball (in blue) compared to a more generic left-handed release point (in red).

Hader’s pitch, thanks to its slanted approach angle, ends up off the plate; the average pitch ends up in the zone. But for Freeman, both these pitches appear to be headed for the strike zone at the time he has to make his swing decision (in green). At that moment, the offerings cross paths, but they end up in very different places. Combine this with the fact that Hader basically releases the ball behind Freeman’s line of sight, and it’s no wonder his fastball is so dominant, especially against lefties. Throughout his career, nearly 46% of left-handed hitters tasked with facing Hader have gone down on strikes.

Quickly down 0–2, Freeman may as well forfeit the at-bat right here. Batters have collectively hit .066 against Hader after an 0–2 count, and even Freeman isn’t his usual self after getting behind, with just a 50 wRC+. But now it’s his turn to kick into high gear.

After seeing where the first two offerings got him, Hader attempted to put his adversary away with another fastball, leveling it up to 98 mph. But Freeman stayed alive, fouling it off. Then he fouled off a fourth consecutive heater, and a fifth for good measure:

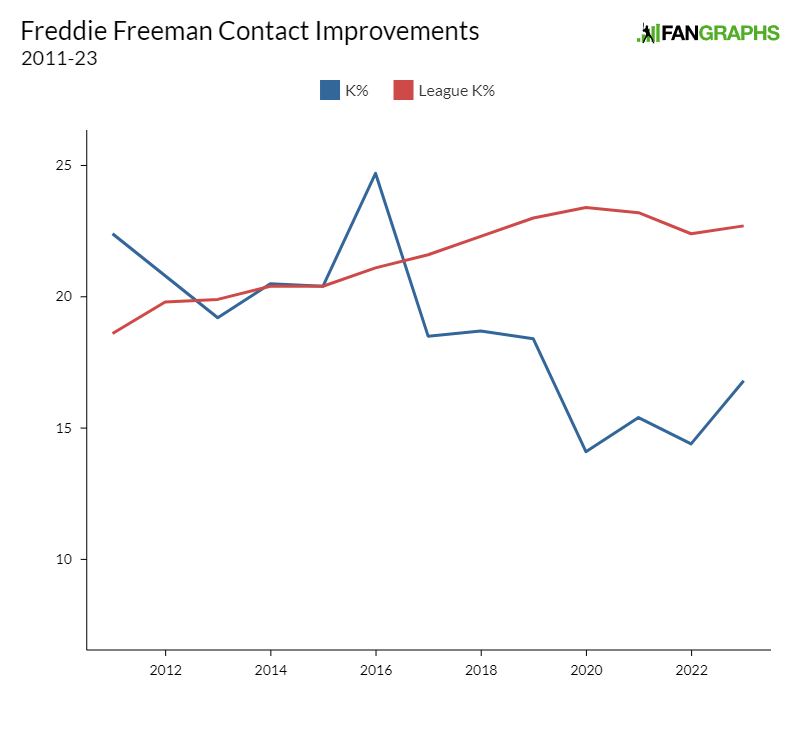

Freeman entered the league striking out at roughly a league-average rate but has significantly cut down his strikeouts as the years have passed — especially impressive when considering the league-wide explosion in whiffs during this time. Many power hitters utilize big uppercut swings to lift balls over the fence. While Freeman does have the fourth-best slugging percentage in the NL, he has a flatter swing that allows him to stay on plane with Hader’s shallow vertical approach angles, giving him an advantage over other hitters as the pitching meta has shifted toward flat heaters at the top of the zone. In addition to fewer strikeouts, we’ll see even more benefits to Freeman’s bat path later in this matchup.

The past three pitches showed that Freeman wouldn’t be fooled by another fastball, so Hader went to his next offering: the slider. While Hader gets pure rise on his fastball with 99% spin efficiency, his breaking ball is thrown with almost pure gyro spin, with only gravity affecting its trajectory until the late, sharp cut to the side as it approaches home plate. It’s his best-performing pitch especially with two strikes, leading his arsenal in putaway rate and drawing whiffs on over half of the swings against it. Hader’s only issue is location: while his fastball heat map has a clear concentration up in the zone, his slider ends up all over the place. But with this 0–2 pitch, he put the ball exactly where he wanted it.

Hader landed this slider just a couple inches off the plate and below the zone, creating a near-perfect tunnel with a fastball headed toward the outer half of the plate. It’s immaculate location for one of the best whiff pitches in the league. But Freeman didn’t swing. He didn’t just lay off the pitch; he saw where it was going every inch of the way and had no trouble whatsoever keeping the bat on his shoulders.

In the Statcast era, there have been over 12,000 left-on-left breaking balls thrown in the shadow of the strike zone low and away. Batters swung at over 57% of those pitches, and pitchers racked up a swinging strike rate of 29.9% — roughly the same as that of Spencer Strider’s slider. Add in the additional requirement of a two-strike count, and that swing rate jumps to 73.4%. Most hitters would be walking back to the bench after seeing that pitch from Hader. But not Freeman.

Once down 0-2 in the count, Freeman is about to see a seventh pitch in this at-bat. Hader and Campusano are running out of options; Freeman was geared up to hit the fastball after seeing five of them, and he wouldn’t chase even an excellently located slider. So Hader pivoted to plan C, hoping to catch Freeman off guard:

Hader has thrown 934 pitches this season; that was only the second lefty-lefty changeup he’s thrown all year and just the ninth of his career. He had no intention of letting Freeman’s bat get anywhere near that ball — watch how Campusano readied himself for the block attempt before the pitch is thrown — but he didn’t bite. Freeman has always had a disciplined approach, running chase rates between the 60th and 70th percentile each season. But his 11.6% career walk rate is much closer to the top of the leaderboard. He’s currently on track to post an OBP above .400 for the second year in a row and fifth time in his career.

The count is now 2–2. Hader doesn’t want to throw another waste pitch and force the count full, so he has to throw something competitive here. With less than one-third of his sliders finding the strike zone, the natural choice to attack Freeman is to go back to the sinker. It’s the pitch that put Hader in the driver’s seat in the first place, but also the one Freeman has seen the most. Campusano set up high, but Hader missed his spot low and away. It’s still well-located, avoiding the heart of the plate, and the barrel of Freeman’s bat would have to travel a long way to square up this ball. Let’s see how this eight-pitch showdown ends:

Freeman laced a line drive to right field, 107.4 mph off the bat. He crawled out of his 0–2 hole, slowly gaining familiarity with Hader’s fastball, laying off the secondaries, then finally winning the battle once Hader went back to the heater.

With that swing, Freeman demonstrated the most important part of his offensive skillset: the ability to crush any pitch on a line with his plus bat speed and level swing path. He has over 300 career homers and has reached 30 or more in three separate seasons, but what truly separates him from other sluggers is what happens when the ball stays in the yard. Since his first full season, Freeman leads the league in doubles by a wide margin and ranks fourth in BABIP despite being a below-average runner thanks to his prodigious line drive rate.

In the Statcast era, we have access to sweet spot rate, or the percentage of batted balls hit between 8–32 degrees — a range encompassing line drives and low fly balls. Batters have slugged 1.091 on balls in the sweet spot this season independent of exit velocity. Unsurprisingly, Freeman has dominated in both metrics, with top-three finishes nearly every season.

| Year | Sweet Spot% | Ranking | LD% | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 43.4 | 2nd | 27.8 | 3rd* |

| 2016 | 44.7 | 2nd | 29.1 | 1st |

| 2017 | 40.1 | 13th | 24.5 | 11th |

| 2018 | 44.7 | 4th | 32.3 | 1st |

| 2019 | 40 | 18th | 27.5 | 2nd |

| 2020 | 49.2 | 2nd | 31.1 | 1st |

| 2021 | 37.2 | 43rd | 24.4 | 12th |

| 2022 | 42.9 | 2nd | 27.5 | 1st |

| 2023 | 47.6 | 1st | 28.4 | 2nd |

At the age of 34, Freeman is on pace to set a full-season career high in wRC+ and is embroiled in a three-way race for NL MVP. To date, he’s amassed 2,100 career hits and has reached base safely over 3,000 times. That success is the result of a long career where he’s been excellent at nearly everything — contact, patience, hitting line drives — and even improved in areas like strikeouts and baserunning despite being on the wrong side of the aging curve. We can look at season and career stats and see Freeman near the top of every leaderboard. But sometimes, it takes just one plate appearance to see what a special player looks like.

Kyle is a FanGraphs contributor who likes to write about unique players who aren't superstars. He likes multipositional catchers, dislikes fastballs, and wants to see the return of the 100-inning reliever. He's currently a college student studying math education, and wants to apply that experience to his writing by making sabermetrics more accessible to learn about. Previously, he's written for PitcherList using pitch data to bring analytical insight to pitcher GIFs and on his personal blog about the Angels.

Freeman seems to see Hader well. He was untouchable in Game 4 of the ‘21 NLDS, until Freddie stepped to the plate. The rest is history.