Where Do We Draw the Line Drive?

I still remember the first time I wondered, What if the colors I see aren’t the same ones that other people see? What if the color I perceive as red looks the same as what you perceive as yellow? I was 10 years old, and I felt like a budding scientist or philosopher, or perhaps a poet. Whichever one, I was already preparing my Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

I’ve since come to realize that my 10-year-old brain wasn’t asking anything that every stoned college freshman hadn’t asked before. I sounded less like a Nobel Laureate and more like John Kruk taking his role as the Phillies’ color commentator a bit too literally. That said, the idea that different human beings perceive colors in different ways isn’t just pot-fueled postulation or Krukian wisdom – it’s the truth. It would have blown my 10-year-old mind to learn the colors I see aren’t necessarily the colors everyone else sees, and it’s not just about rods, cones, and intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Sometimes, it’s a matter of language.

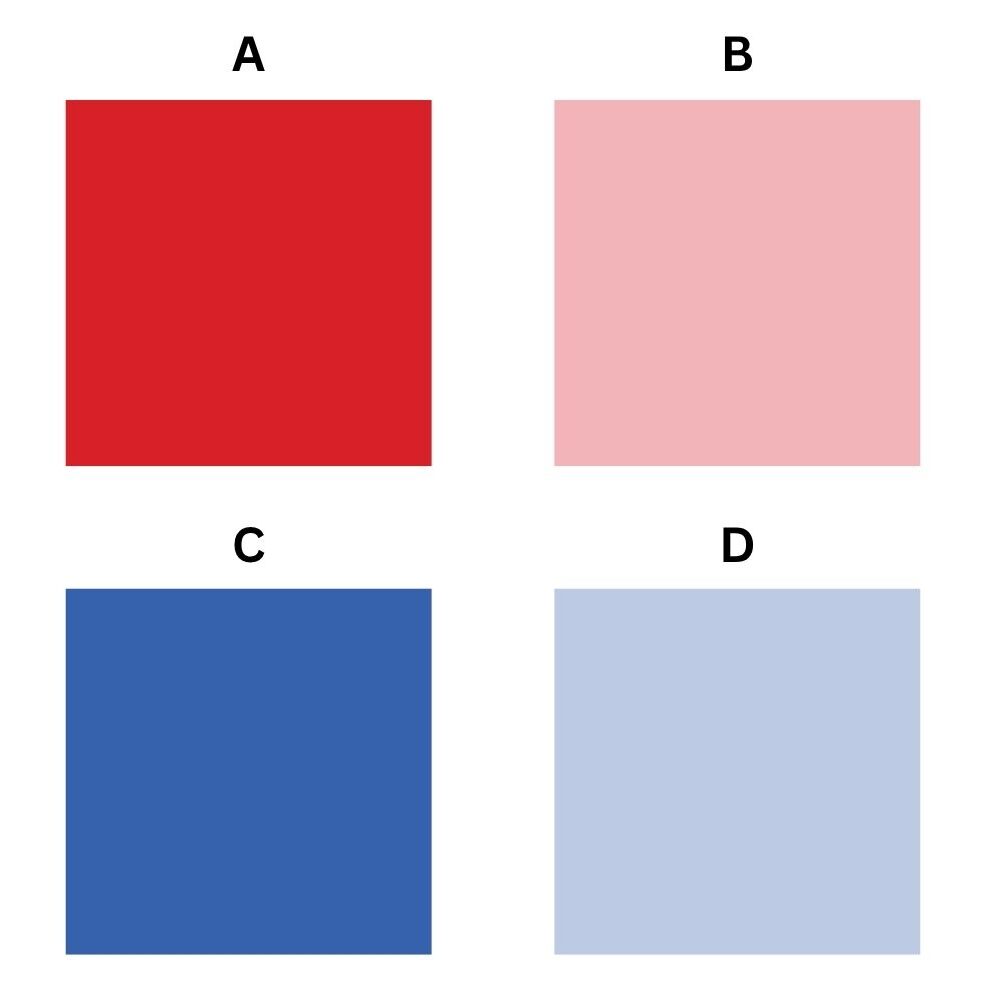

Take a look at the four swatches below. Think about what colors they are. And no, the answers aren’t Steven Kwan’s whiff rate, arm strength, bat speed, and sprint speed:

In terms of lightness and saturation, the difference between swatches A and B is roughly the same as the difference between swatches C and D. Yet, if I showed you the swatches one at a time and asked you to name each color, you’d probably give different answers for A and B (red and pink, respectively) and the same answer for C and D: blue. It would be the same if C and D were two different tones of orange, yellow, green, or purple. English speakers think of “red” and “pink” as distinct color categories in a more significant way than we do for shades of any other hue.

That’s not the case for all languages. In Russian, for instance, the words “синий” (romanized as “siniy”) and “голубой” (romanized as “goluboy”) refer to darker and lighter blue. What is particularly fascinating about this is that having two different words for darker and lighter blue has been shown to help Russian speakers distinguish between the two shades more quickly and accurately than English speakers. So, some cognitive psychologists theorize that the languages we speak don’t just describe the material world. They influence the way we perceive it.

(A brief aside: When the Royals drafted Victor Cole, the most recent Russian-born player to appear in the major leagues, I wonder if they knew that no one else was better suited to distinguish between the dark and light blues of their uniforms?)

As a monolingual English speaker, I can barely comprehend how someone could see different shades of blue as separate colors – even though I do the same with red and pink. It feels as strange as calling hot pizza and cold pizza two different foods or left socks and right socks two different items of clothing. Yet, someone from Russia might be equally confused that I can’t easily distinguish between siniy and goluboy. It’s not about any intrinsic property of the colors. It’s all about language. Indeed, researchers have found similar effects in various areas beyond color, including the perception of everything from objects and quantities to time and space. What about line drives?

Batted balls are traditionally sorted into three primary buckets based on their vertical direction and another three based on their horizontal direction. Right now, I’m interested in the vertical buckets: groundballs, fly balls, and line drives. Sports Info Solutions keeps track of batted ball data, which we house here at FanGraphs, so you can find those numbers alongside traditional stats like singles, doubles, triples, and home runs. With a few quick clicks, I can tell you Jose Altuve is the active leader in groundballs, just like he’s the active leader in singles, and Freddie Freeman is the active leader in line drives, just like he’s the active leader in extra-base hits. I was more surprised to learn Nolan Arenado is the active leader in fly balls, and I think that’s partially because of how often he pops out. When I remove infield fly balls from the data, Andrew McCutchen jumps to the top of the leaderboard. Therein lies the issue at the heart of this piece: There are no cut-and-dried rules for sorting batted balls. If you looked at Baseball Savant instead of our leaderboards, you wouldn’t find Arenado or McCutchen sitting atop the fly ball rankings. Rather, you’d see Carlos Santana (if you included popups) and Freeman (if you didn’t).

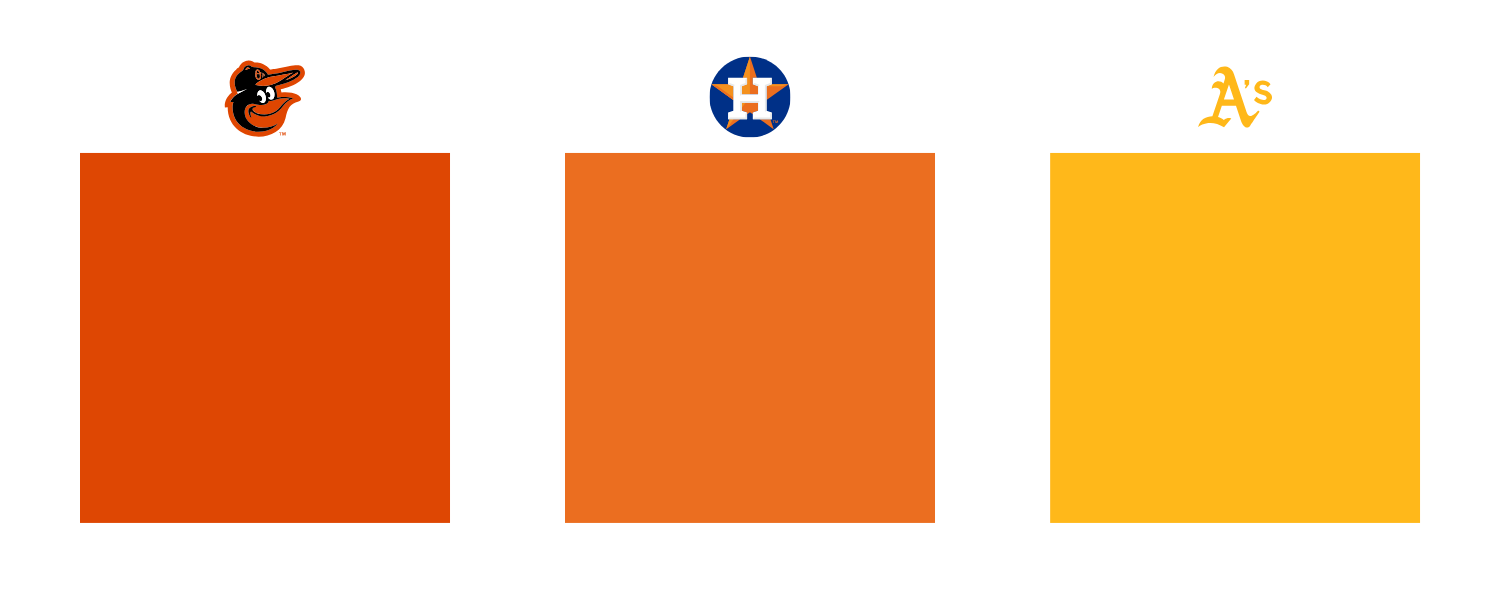

Unlike singles, doubles, triples, and home runs, the different types of batted balls aren’t discrete categories. As with colors, they exist on a spectrum. Consider the swatches below. I took the colors directly from three team logos on MLB.com:

The Orioles’ and Astros’ logos are both orange. Whether you’d call the Athletics’ logo yellow or gold, what matters is that it’s in a different color category than the other two – even though the difference between Astros orange and A’s yellow really isn’t that much greater than the difference between Orioles orange and Astros orange. All three colors exist somewhere along the spectrum from red to orange to yellow, but two of them are “same” and one is “different.”

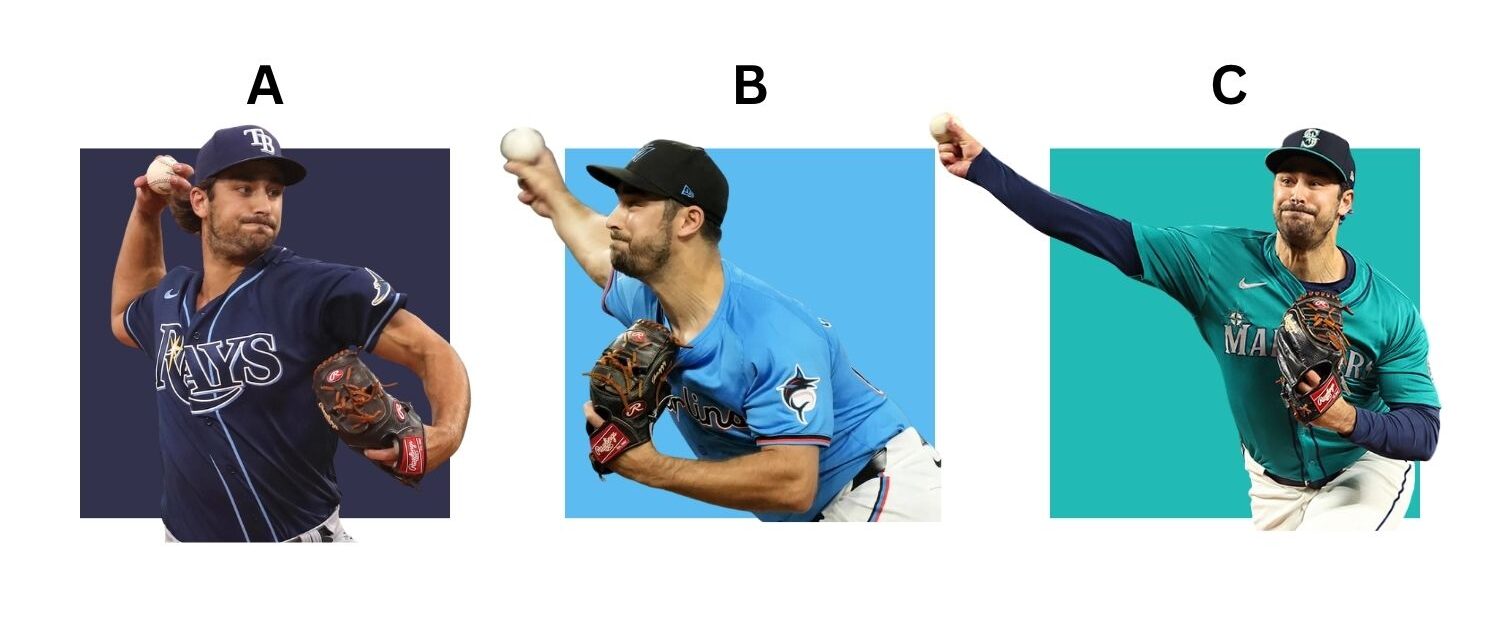

Now, consider the three batted balls in the clips below:

Each came off Trea Turner’s bat at the same speed (98 mph), and the difference in launch angle between the first hit and the second hit is the same as the difference in launch angle between the second and the third. However, the first two were groundballs, according to both SIS and Statcast, while the third was a line drive. All three hits exist along the groundball-to-line drive spectrum, but as with the colors, two of them are “same” and one is “different.”

This isn’t a grand revelation. I’m hardly the first person to write about the blurry line between groundballs and line drives and the even blurrier border separating line drives and fly balls. What I’m wondering is if the reason these two are classified as separate types of batted balls…

…while these two are both line drives…

…is the same reason why we’d say JT Chargois is wearing the same color in exhibits A and B but a different color in exhibit C. Is it all about language?

Categorical perception describes the human tendency to view differences between items within categories as much smaller than differences between items in separate categories, even when those differences are of the same magnitude. In other words, once we have created categories, intra-category differences can seem less important than inter-category ones.

For example, research participants have been found to perceive differences between varieties of one color and differences between varieties of another color as much smaller than equal-sized differences that traverse the boundary between those two colors. This helps explain why separating blue into two categories (siniy and goluboy) allows Russian speakers to better distinguish between shades of blue. On the flip side, it helps explain why English speakers are worse at distinguishing between darker and lighter blues.

I think we have the same problem with line drives. According to the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, the first known use of the term “line drive” was in an 1876 issue of the Chicago Tribune, though it was also used at least a year earlier to describe a similar type of batted ball in cricket. That means the term predates what we know today as Major League Baseball, and it has been around since long, long before we had any way to measure launch angle or exit velocity. It’s the same for “groundball” and “fly ball” (and “popup”). Does it really make sense that we’re still using the same primary categories for batted balls that have been around for almost as long as the game itself? I mean, maybe. But at the very least, it’s worth considering that we only treat line drives as a single, unified category because that’s all we have the language to describe.

The color term “blue” implies a defined category, distinct from green, red, etc., and encompasses every shade from navy to powder. In the same way, the term “line drive” implies a defined category, distinct from groundballs and fly balls, and encompasses all forms of contact from low screamers to frozen-rope home runs. Yet, I wonder if it wouldn’t be more useful to split line drives into two categories: low line drives and high line drives. Using the qualifiers “low” and “high” makes it seem like I’m discussing subcategories, but that’s only because a lack of specific language forces subcategorization. You don’t need to say dark and light blue when you have siniy and goluboy.

Over the past three seasons, major league batters have hit nearly 75,000 line drives, per Statcast. The median launch angle of those 75,000 line drives is somewhere around 16 to 17 degrees. That’s also the approximate midpoint between where line drive batting average peaks (12-13 degrees) and line drive ISO peaks (21 degrees). So, 16 degrees seems like the right upward cutoff point for a “low liner,” and 17 degrees seems like the right starting point for a “high liner.” Using those definitions, here’s how the two types of batted ball have performed since 2023:

| Batted Ball | BA | ISO | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Liner | .752 | .187 | .731 |

| High Liner | .514 | .325 | .563 |

Close to 58% of low liners have turned into singles, compared to 27% of high liners. Meanwhile, high liners are about 130 times more likely to be home runs. Out of more than 38,000 low liners from the past three seasons, just 10 have left the yard. That’s not so surprising; a batter has to absolutely smoke the baseball to get it over the fence with a launch angle under 17 degrees. Nonetheless, low liners are far more productive than high liners because they’re so much harder to catch. Only a quarter of low liners turn into outs, while high liners find a fielder’s glove almost half the time.

Here’s how those numbers look compared to the same stats for groundballs and fly balls:

| Batted Ball | BA | ISO | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groundballs | .248 | .024 | .228 |

| Low Liner | .752 | .187 | .731 |

| High Liner | .514 | .325 | .563 |

| Fly Balls + Popups | .209 | .429 | .340 |

The difference in ISO between high liners and low liners is almost as big as the difference in ISO between low liners and groundballs. Similarly, the difference in batting average between low liners and high liners really isn’t that much smaller than the difference in batting average between high liners and fly balls. So, in terms of the results they generate, low liners and high liners are roughly as different from one another as they are from any other type of batted ball. There’s also a visual component. Low liners more closely resemble groundballs, while high liners have more in common with fly balls, and that’s not just because of each’s proximity to the ground. Low liners, like groundballs, are more likely to be hit to the batter’s pull side. Meanwhile, high liners, like fly balls, are less likely to be pulled than they are to be hit straightaway or to the opposite field:

| Batted Ball | Pull Rate | Straightaway Rate | Opposite-Field Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groundball | 49.2% | 38.6% | 12.3% |

| Low Liner | 42.4% | 36.4% | 21.2% |

| High Liner | 34.6% | 36.8% | 28.6% |

| Fly Balls + Popups | 27.0% | 36.7% | 36.3% |

You could argue that all this proves is that batted balls exist on a spectrum, which was never up for debate. After all, you might think, we could chop up any type of batted ball into any number of smaller groups and come away with different stats for each subtype. That might well be true, but by that line of thinking, there’s no point in categorizing batted balls at all.

No one would disagree that the precise cutoff points for any system of batted ball classification are arbitrary. Still, batted ball types are an incredibly useful tool for describing and analyzing the game. Meaningless cutoff points are a necessary evil in the creation of categories that absolutely do matter. So, this has never been a question of finding the “correct” dividing lines between different types of contact. Rather, it’s about being open to the idea that a few terms invented 150 years ago aren’t the be-all and end-all of batted balls.

So why high and low line drives? I could show you the stats for high and low groundballs or high and low fly balls, but it wouldn’t be as interesting. A groundball hit too low is just poor contact. The same goes for a fly ball hit too high. Low and high line drives, however, are both effective but in different ways. Low liners are valuable because they’re much more likely than groundballs to go for singles. High liners are valuable because they’re much less likely than fly balls to be caught when they don’t escape the yard.

That’s pretty much the crux of the matter: Low liners and high liners succeed in different ways. To that point, consider the pronounced difference in average exit velocity and hard-hit rate between low and high liners:

| Batted Ball | EV | Hard-Hit% |

|---|---|---|

| Low Liner | 97.0 mph | 65.1% |

| High Liner | 90.7 mph | 42.8% |

It makes intuitive sense that low liners, on average, are hit harder; if they weren’t hit hard enough, they’d touch the ground too soon and be labeled groundballs instead of line drives. The thing is, while low liners are more likely to be hit hard, they don’t need to be hit as hard in order to be successful. Hard-hit low liners have a wOBA 15% higher than non-hard-hit low liners. Hard-hit high liners have a wOBA 38% higher than non-hard-hit high liners. Even so, they still aren’t as valuable as their hard-hit low counterparts:

| Batted Ball | wOBA |

|---|---|

| Low Liner (Hard-Hit) | .766 |

| Low Liner (Not Hard-Hit) | .665 |

| High Liner (Hard-Hit) | .670 |

| High Liner (Not Hard-Hit) | .484 |

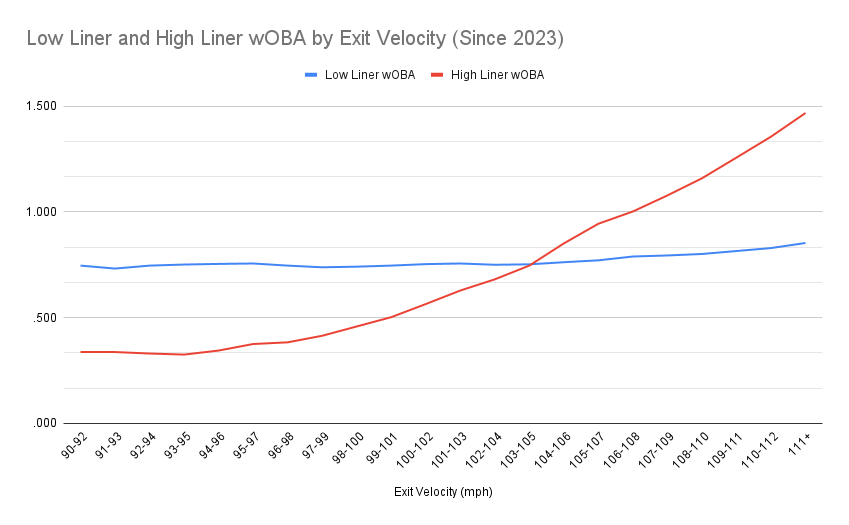

The other side of that coin is that high liners have far more to gain from additional exit velocity. At an exit velocity of around 105 mph, high liners finally eclipse low liners in productivity, and they only get more valuable the harder they’re hit. Low liners, on the other hand, are all similarly productive at any exit velocity between 90 and 104 mph, and they only become marginally more productive with each added mile per hour above 105:

The simple explanation for this is low liners and high liners have different goals. All else being equal, hitting the ball harder is almost always going to lead to better results at the plate. That said, exit velocity makes a much bigger difference if you’re going for extra bases. The difference between a double and a home run is often just a few miles per hour of exit velocity. When it comes to hitting singles, however, sometimes it’s equally effective to dink the ball in front of the outfielders as it is to send it over their heads.

On a related note, the difference between low and high line drives has grown more pronounced in recent years. Baseball Prospectus’s Russell Carlton has written about line drives extensively, noting that they are being caught at a higher rate than in the past and, perhaps in response, line drive rates have declined. Yet, according to the Statcast data, those effects haven’t been the same for both low and high line drives.

Low line drives, which are less susceptible to being caught, actually have a higher batting average over the past three seasons than they did in the first three years (or any other three-year period) of the Statcast era. That’s all the more impressive considering the league-wide BABIP has declined substantially, dropping from .300 from 2015-17 to just .293 from 2023-25. Additionally, the low line drive rate has only declined by half as much as the high line drive rate. As a result, batters continue to generate almost as much value with low line drives as they did at the beginning of the Statcast era. In contrast, high line drives have become a far less plentiful source of runs:

| Low Liners | High Liners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | BA | % | RV / 162 | BA | % | RV / 162 |

| 2015-17 | .738 | 12.7% | 109 | .552 | 12.6% | 153 |

| 2023-25 | .752 | 12.2% | 98 | .514 | 11.6% | 60 |

I hope all this was enough to convince you that low liners and high liners are useful as distinct categories for describing and understanding the game. There will never be a perfect way to slap labels onto a spectrum. Dividing lines will always be fuzzy, and language will always limit the labels we create. Even my proposal to split line drives in two is biased by language; if there were a common English word for “medium height,” perhaps I’d be suggesting three new groupings instead of just high and low.

Ultimately, however, I’m not too concerned with whether high and low line drives are the perfect categories to suggest, or if I’ve split them up the proper way. What matters to me most is simply considering the possibility that such additional categories exist. If language is the only thing holding us back from perceiving blue as two discrete colors, maybe it’s also the only thing stopping us from seeing line drives as two different types of batted balls. Perhaps it’s time to open our eyes to the siniy and goluboy of line drives.

All stats through June 29.

Leo is a writer for FanGraphs and MLB Trade Rumors as well as an editor for Just Baseball. His work has also been featured at Baseball Prospectus, Pitcher List, and SB Nation. You can follow him on Bluesky @leomorgenstern.com.

For the record, I agree with Kruker about Caillou.