Why Is It Always the Year of the (Insert Pitch Here)?

You may have noticed that this is the Year of the Kick-Change. And you may have noticed that last year was the Year of the Splitter, and the two years before that were the Year(s) of the Cutter, and before those years came the Year of the Sweeper and the Year of the High Four-Seamer. You may have noticed that there have been a lot of Years lately, is what I’m saying. And that’s before we even get into the Summer of the Gyro Slider, the Month of the Death Ball, the Fortnight of the Vulcan Change, the Week of the Slip-Change, and the glorious Day of Rasputin’s Cradle. We seem to be living in some sort of pitch type zodiac calendar and I’d like to talk about why that is. If you’re a regular FanGraphs reader, I may not say any one thing that’s totally new to you, but I think there’s value in putting all the pieces together to give a sense of the way pitching has evolved in recent years.

When I interviewed for this job back in 2022, one of the questions I had to answer was, “What do you think is the story of baseball right now?” My answer was pitch design. It felt like every day we’d learn about some new innovation in training, technology, or biomechanics that allowed pitchers to discover new pitches and refine the ones they already had. Although plenty has happened over the last three years, if you asked me that question again today, I’d probably give you the same answer.

Let’s start specific and then we’ll widen our lens. This is the Year of the Kick-Change (and as such, let’s take a moment to pity the poor kick-change). Eno Sarris wrote a whole breakdown of the pitch for The Athletic just yesterday. For the most part, a kick-change moves like any other changeup. As this explainer from Tread Athletics demonstrates, pitchers can throw a kick-change with any one of several changeup grips; the only difference is that their middle finger is spiked, meaning it is flexed with the fingertip against the ball so the knuckle looks like a spike rising off it. Here’s Clay Holmes demonstrating the grip for SNY.

That flexion means that as the ball rolls off the pitcher’s fingertips, the middle finger has less effect on the ball’s spin, and the ring finger has more. The middle finger, located more centrally, tends to impart more backspin, while the ring finger, located more toward the outside of the ball, imparts more side spin. Taking the middle finger away allows the ring finger to tilt (or kick) the spin axis, imparting more gyro spin (and possibly killing some of the overall spin), which causes the pitch to sink more. That’s it. That’s the whole deal. The kick-change takes away your middle finger, allowing your ring finger to subtly change the spin, which means more sink. If you’ve ever stayed up at night wondering why you can give the middle finger but you can’t take it, you can rest easy now. If you throw a kick-change, you can finally take the finger.

Now let’s back up. How do we know all this? How do we know that spiking the middle finger allows the ring finger to have more say over the spin, and how do we know that the result is more drop? We now have Edgertronic cameras capable of recording thousands of high-definition frames per second. If you saw any pictures or videos of pitchers throwing bullpen sessions during spring training, you absolutely saw tiny Edgertronic cameras perched on a tripod right behind their shoulders, zoomed in on the spots where they’d be releasing the ball. Those cameras allow us to see how the tiniest change in grip, finger pressure, seam orientation, you name it, affects the way the ball leaves a pitcher’s hand.

Those spring training pictures and videos also showed portable Trackman units on their own tripods, usually behind the catcher. Trackman instantly tells you all the characteristics of a pitch: velocity, release point, spin axis, movement, and so on. Pitchers have always tinkered and had pitching coaches to guide them, but with the marriage of those two technologies, they can instantly put an exact number to any adjustment they make.

Time for another step back. Having those numbers is huge, but in recent years, they’ve become even easier to use because advanced stuff metrics like Stuff+, PitchingBot, StuffPro, and PLV can help us interpret them. The stuff metrics look at the results of thousands upon thousands of pitches in order to put a grade on any pitch, and they’re constantly being refined. Adjust the seam orientation on your slider or try spiking your middle finger on a changeup, and you can get instant feedback on whether you’ve improved the pitch. Sometimes the insights from the stuff metrics merely confirmed what we already knew – turns out throwing your fastball harder is a good idea. They also helped spark plenty of new insights and explain concepts like the dead zone, in which pitches that looked for all the world like they should have been racking up whiffs instead failed to do so because their movement turned out to be too predictable.

With this next step back, let’s stop and ask ourselves a question: Why does everybody need a changeup in the first place? In 2008, offspeed pitches made up just 11% of all pitches, but that number has grown steadily and sits at 14.1% so far in 2025. Clearly pitchers think they need more changeups. Some of them think they need two. During spring training, I happened to catch Chris Bassitt giving an in-game interview. He explained why he throws both a regular changeup and a splitter. “I need a lot of depth,” said Bassitt, whose regular changeup has roughly the same vertical movement as his sinker. “The splitter has a lot of depth to it, so it works for me because it’s way off my sinker.” Bassitt throws eight pitches, including two different offspeed varieties, because he needs that movement separation.

The newest twist on the stuff metrics came just a few months ago, when Stephen Sutton-Brown introduced new arsenal metrics at Baseball Prospectus. Some stuff metrics had played with this idea to an extent, but Sutton-Brown was able to analyze the way different pitches play off one another, rather than viewing each pitch in isolation. There are four metrics: pitch-type probability, movement spread, velocity spread, and surprise factor. Sutton-Brown was, to some degree, able to put grades on concepts like pitch tunneling and the ideal velocity separation between a pitcher’s fastball and changeup. Another of the biggest takeaways was that pitchers with deeper repertoires perform better, especially later in games, when batters have already seen them once or twice. In other words, it’s no longer just a good idea to take advantage of pitch tunneling and to throw pitches with a wide variety of movement profiles. Now, it’s also a good idea that can be quantified and optimized.

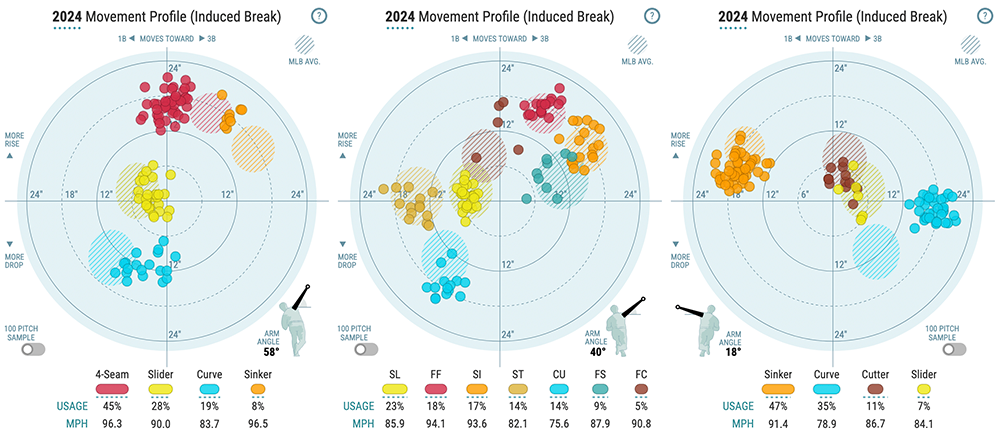

Last year, Baseball Savant rolled out a new graphic for the top of the player pages. It lays out each pitcher’s repertoire and movement profile on a compass, giving you an excellent sense of how each pitch interacts with the others. On the left is Tyler Glasnow’s chart, in the middle is Yu Darvish’s, and on the right is Brennan Bernardino’s.

You can see why so many websites have been scrambling to come up with similar graphics. Even a cursory glance tells you so much about a pitcher. Glasnow has an extreme over-the-top delivery that lends itself to North-South movement. Bernardino is a side-armer with an East-West movement profile, while Darvish comes out of a standard slot and throws everything but the kitchen sink. You can also see what a pitcher might need. If I’d showed you Bernardino’s 2023 chart, you wouldn’t have seen a cutter or a slider. His chart was crying out for an offering that could bridge the gap between the sinker and curve in order to provide some semblance of pitch tunneling.

The new metrics are telling pitchers that they need to diversify their offerings, and pitchers are listening. All around baseball, pitchers, especially starters, are adding new pitches at a furious pace and figuring out their optimal usage rates. Paul Skenes looked like arguably the best pitcher in baseball last season, and he came back with two additional pitches this year. The thing is, we’ve always known (or at least always intuited) that having a wider array of pitches was a good thing. Why is this trend taking off right now? Time for another step back.

Not every pitcher is Darvish or Bassitt. Not every pitcher can throw every pitch. All pitchers have different tendencies, and we’ve learned about new ways to analyze their biomechanics in order to understand and make the most of them. In recent years, we’ve spent more time talking about pronation and supination. I’m just going to pull an explanation from an article I wrote last year: There’s a wide spectrum, but some pitchers tend to be better at supinating when they throw — turning their palm inward as they would when doing a karate chop. Some tend to be better at pronating — turning their palm outward as they would when telling someone to talk to the hand. Pronators tend to have higher release points and greater spin efficiency on their pitches. To put it in the simplest possible terms, supination helps you throw a sweeper, and pronation helps you throw a changeup.

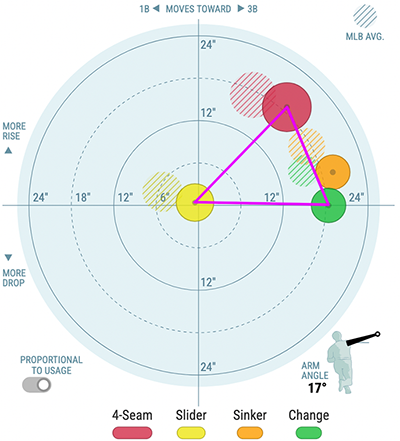

If you’re a classic pronator, you’ll get plenty of arm-side movement, but you’ll struggle to get glove-side break on the ball. Even your slider will end up with basically no horizontal break at all, because you’ll have to throw it with gyro spin rather than side spin. At Baseball Prospectus, Mario Delgado Genzor identified a movement pattern that he named the pronator’s triangle, using Luis Castillo’s as an example. There’s the slider, which basically has null movement, the four-seamer getting some rise and plenty of arm-side run, and the changeup (and sinker) getting pretty much all arm-side run.

On the other hand, if you’re a dyed-in-the-wool supinator, you’ll probably throw great breaking balls but struggle to throw a changeup. Your arm just doesn’t want to move that way. In the past, the result was simple: You didn’t throw a changeup. But many of the changeup variations are designed to allow those pitchers to get the sink and arm-side run of a classic changeup. The kick-change alters the spin axis, while a splitter or a Vulcan change kills spin, causing the pitch drop off the table as it approaches the plate. Voila, now you’re a supinator who throws a changeup. These days, players spend their offseasons at facilities like Driveline Baseball and Tread Athletics, and teams have pitching labs where they’re doing biomechanical analysis of their pitchers, figuring out not only how they work but how they could work.

That’s just one implementation of biomechanical analysis. There are plenty more. If you want to talk about pitchers whose deliveries are more rotational than linear, Michael Rosen wrote a whole article about Cole Ragans’ pelvis, and now that I know that, I will bring it up every single time I speak to Michael. Here’s a great portion of an interview David Laurila did with Logan Webb last year, in which Webb discusses the process of finding the right arm slot.

Webb: “Like I said, I came back from TJ and was throwing a little bit harder. They actually moved me up. They kept telling me they wanted me to throw like Tyler Glasnow, Walker Buehler, and a bunch of these guys. So I moved [my arm slot] up, and I couldn’t do it. When I got called up [in 2019], I was still maybe over the top a little bit too much.

“Then we hired [director of pitching] Brian Bannister. He called me and said, ‘We’re going to drop you down.’ This was on December 26 or 27, going into 2020. They were going to have me throw like Chris Sale and Corey Kluber. I was a little shocked at that.”

Laurila: I assume you asked why?

Webb: “I did ask why. They thought that was my natural arm slot, and with the way my hand comes through it would be a good thing to move down. So I did that. It was a big learning curve. It took me about a year to really figure it out. After that, it’s just been kind of refining it, keep trying to get better and better at it each year.”

Laurila: Can you elaborate on why it’s a good arm slot for you?

Webb: “The way my hand comes through… I’m a heavy supination pitcher. When I drop down and throw that supinated pitch, it creates the seam shift for everything — the two-seam and the changeup. I didn’t know about any of this until I got with [Bannister] in spring training. He kind of showed me how it worked. Like I said, it took me a long time to figure it out, but I’m happy I did that.”

All of this is to say that the same tools that have helped pitchers improve in recent years have also helped create all the trends we’ve seen. You can trace many of these Pitches of the Year back to a particular breakthrough in our understanding of pitching (and sometimes hitting). The high four-seamer came into vogue for a couple of reasons. The launch angle revolution had batters adopting steeper swings, which made them susceptible to high heat. But we were also starting to understand the importance of spin rate, so pitchers who could get a lot of rise on a four-seamer were finally given license to make the most of it, rather than being told to keep the ball down.

As a result, four-seamers made up an increasing percentage of all fastballs. But around 2019, four-seamer and sinker usage started to find their levels. We started to understand the importance of induced vertical break: Flat four-seamers play better up in the zone and steep sinkers play better down in the zone. This knowledge allowed pitchers the flexibility to throw the fastball that worked best for them.

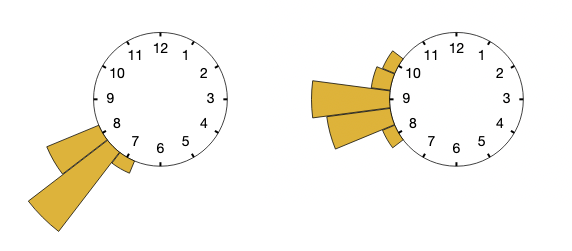

The sweeper craze piggybacked off a newfound understanding of seam-shifted wake — the movement that results from the orientation of the ball’s seams, not just the ball’s spin axis. Courtesy of Baseball Savant, the clock on the left shows us how we’d expect Pablo López’s sweeper to move just based on its spin. The clock on the right shows us how it actually moves.

Our understanding of pitch tunneling made cutters, which tend to sit between fastballs and breaking balls in terms of movement, more attractive. More recently, understanding each pitcher’s biomechanical tendencies has helped to expand the population of pitchers who are capable of throwing an effective offspeed pitch. And we’re not done. Just two days ago, Lance Brozwdowski posited that the Yankees are teaching their pitchers a new one-seam sinker that allows even high-slot guys like Carlos Rodón and Max Fried to get more sink on the pitch while increasing velocity.

Part of the reason these trends were so notable is because they involved more players than they should have. These ideas spread across the league because they worked for some pitchers, but they also swept up plenty of pitchers for whom they weren’t right and didn’t work. Besides, none of these pitches is necessarily new. Sandy Koufax was famous for the rise on his fastball and the bite on his curveball. Plenty of pitchers threw wipeout sliders that we’d now call sweepers or sinking sliders that we might call death balls. Kick-changes have been around, too. However, all of these advances have made more pitch types than ever accessible to pitchers, and the advanced training methods have made it possible for them to learn multiple new pitches in a hurry. Take Boston rookie Richard Fitts, who came into spring training boasting not only increased fastball velocity, but a modified changeup and an entirely new curveball and sinker. He did all that in one offseason. So when the Yankees and the Dodgers start teaching their pitchers to throw sweepers, other teams take note, look at the data, and try it with their own pitchers. When a pitcher needs a platoon neutral offering, everybody knows to try a cutter.

You can look at a pitcher’s movement profile and tell not just what pitches they need, but how they might be able to acquire them. In the before times, a smart person could look at a pitcher and intuit that they really needed a changeup. Now, when a supinator enters the pitching lab, we can put all these resources together. We can say they need to add an offspeed pitch, and based on their movement and biomechanical profile, it should probably be a kick-change. We can tell them it will probably have X amount of vertical and horizontal break, and that its movement profile will grade out as X according to our stuff metrics. In order for them to optimize their overall repertoire, we can recommend that they try to throw it X% of the time to righties and X% of the time to lefties.

I don’t know if this will go on forever. One day pitchers will reach the physiological limits of fastball velocity. There are only 360 degrees and only so many ways that you can make a baseball move. But the battle between hitters and pitchers will always be raging, with constant adjustments on either side. We’ll keep seeing new trends, followed by even newer trends to take advantage of the previous ones. Even if there’s no new pitch under the sun, we’ll probably still see plenty of Pitches of the Year.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

Still waiting for the Year of the Eephus.

Thoughts and prayers that it happens

Or the Year of the Knuckleball?

At least in a video game, a knuckleball & 95+ fastball makes for a wicked combination.

I know it’s not easy, but i’ve always wondered why all pitchers don’t at least try to master the knuckleball. Especially with all the new pitch tinkering that occurs these days.

The adage goes that everyone can throw a knuckler, but very few can throw it for strikes.

With the unnecessary caveat that I’m not a professional…

I’ve been throwing a knuckleball for 20 years. Two years ago was the first time I successfully* threw one off the mound. I had to change my lower half mechanics to make it work. I’m getting to the point where I don’t have to do that anymore.

*Success here is defined as maintaining the lack of spin and illusory aspects characteristic of a knuckler.

I’ve thrown about 10 in a game setting. None for strikes, swinging or otherwise. Never more than two in one game. In the bullpen, I can throw about 1 in 3 for a strike.

That’s just a casual anecdote to show that, yes, it’s hard to get one to men’s league caliber let alone MLB standards. That said, I’m still trying!

(Meanwhile, I picked up a splitter for the first time two months ago and already have 40 or 50 grade command of it. I’ll throw it about 30% when I make my season debut.)

I doubt if he threw 95 but Hall of famer Early Wynn used a knuckleball frequently along with the usual repertoire of pitches.

Yu Darvish circa 2030 will lead that charge. If only Zack Greinke was still around.

Thank you Fangraphs for being one of favorite things about life.