World Wide Webb

For the past half decade, Logan Webb has been one of the game’s premier starters. He churns out 30-start seasons with ERAs in the 3s like clockwork; that’s almost exactly his seasonal average since switching to a full-time sinkerballer in 2021. In that span, he’s averaging 4.4 WAR per year, and he’s topped 200 innings in each of the past two seasons. This year, he’s atop the leaderboards again, with a 2.63 ERA and 2.25 FIP through four starts. But there’s something new to see here, and it’s a change I thought Webb would make for years before he actually did, so I think an updated look is in order.

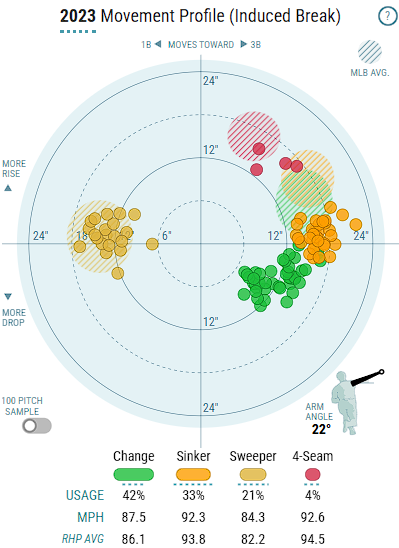

Webb’s approach was simple and yet effective. He threw three pitches to righties: sinker, sweeper, changeup. Against lefties, he threw fewer sweepers and more changeups, and he also mixed in a few four-seamers in lieu of sinkers. For the most part, though, he alternated his three best pitches, weighted to suit the batter he was facing. Here’s a great graphic, courtesy of Baseball Savant’s player pages, that shows Webb’s movement profile. I picked 2023 for reasons that will become obvious shortly:

This shows a few things about Webb’s game in one image. His sinker and changeup move very differently from the league-average versions of those pitches. His four-seamer, rarely thrown, is effective not because of inherent shape, but because it’s different from his primary fastball. His sweeper is the only thing he throws that breaks glove side, and it breaks that way by quite a lot. If you’re facing Webb, you’re either going to see something that tails hard arm side (sinker or changeup) or something that shoots hard glove side (sweeper). It’s like facing Clay Holmes or Blake Treinen for 100 pitches at a time.

That’s quite tough, but it’s at least a solvable puzzle. The place you’re used to seeing the ball go from his arm angle? It’s just not going there. If something comes out of Webb’s hands and appears, to the hitter, to be right down the middle, it’s paradoxically easy to take that pitch. The movement profiles mean that everything will bend away from that initial trajectory.

Despite inarguably good raw stuff – both PitchingBot and Stuff+ give Webb top-15 stuff grades year in and year out – he’s never been a strikeout pitcher. In fact, his swinging strike rates are meaningfully below average. Some of that is because he throws so many sinkers, but even his secondary offerings garner fewer whiffs than you’d expect for pitches with their characteristics.

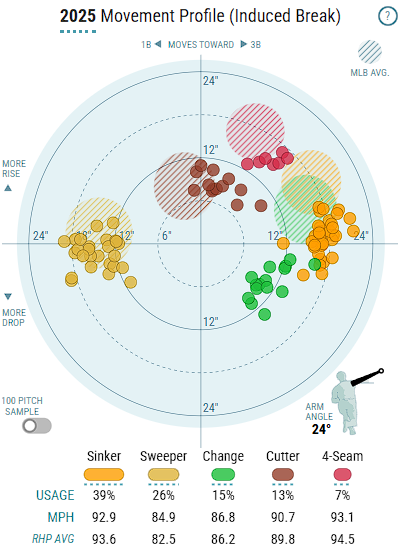

This year, Webb’s pitch movement plot looks a little different:

That big gap in the middle is no longer a gap. That’s because Webb has added a bridge cutter, a pitch he’s now using almost as much as his excellent changeup. In his four starts, he’s thrown that cutter to lefties a quarter of the time.

The idea behind the pitch is simple. Pitching is deception at its core, and Webb was playing with one hand tied behind his back on that front; he didn’t present lefties with enough tough decisions about where the ball would end up. He made his approach work anyway thanks to his pristine command, but it was an uphill battle. Sinkers and sweepers display meaningful platoon splits. You can only throw so many changeups to make up for them. Lefties walk against him roughly twice as often as do righties, and they chase pitches out of the zone less frequently while swinging more often at strikes.

It’s far too early to feel confident in 2025 splits, but Webb has absolutely annihilated lefty opposition so far this year with his new cutter in tow. He’s striking out 31.1% of left-handed batters while walking only 6.7%; for context, he’s run a 22.5% strikeout rate and 5.5% walk rate against all hitters since the start of 2021. His swinging strike rate against lefties is 12.1%, the best mark of his career. The magnitude of his improvement almost certainly won’t hold, but I think the direction will. Despite similar movement, the pitches he throws to lefties when he’s trying to strike them out are all doing much better at that goal:

| Pitch | 2021-2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Sinker | 5.1% | 2.3% |

| Changeup | 14.6% | 18.2% |

| Sweeper | 8.8% | 17.1% |

| Four-Seamer | 12.1% | 13.3% |

So how does this magical cutter look? Pretty forgettable, to be honest. Here’s one he threw to Ben Rice over the weekend in New York:

Boring, right? Our pitch models sure think so. Uninteresting shape, average velocity – the best thing about that pitch was its location, but even then, Rice covered it. But that swing wasn’t particularly comfortable, and I can show you why. Here’s what Webb’s sinker looks like to lefties:

That’s the movement that you anchor off of when you face Webb: Balls that look like they’re inside end up over the middle of the plate. Start a cutter on the same initial trajectory, and it would have stayed off the plate inside. Likewise, start a sinker on the trajectory of the pitch that Rice fouled off, and the ball would have tailed off the plate away. That’s why Rice’s swing looked so awkward; he was leaning out for a pitch that didn’t tail.

The at-bat didn’t end with a cutter; it ended with this innocuous four-seamer:

Ah yes, middle-middle solves the riddle. In Rice’s defense, that was the only four-seamer he saw from Webb all day, and if that had been any other pitch Webb throws, its movement would have taken it out of the strike zone. That’s my point in all of this: By adding to the mixture of pitches he throws, and particularly by finding a pitch that fills the middle of his east-west movement distribution, Webb has made hitters’ jobs harder.

Quantifying the value of this new cutter? That’s a tough job, one I’m glad I don’t have. Over at Baseball Prospectus, Stephen Sutton-Brown developed a method to quantify the value of a diverse pitch mix. This method is broken down into four categories called arsenal metrics. Three of the four metrics are mostly self-explanatory, and the outputs are in percentiles:

| Year | Pitch Type Probability | Surprise Factor | Movement Spread | Velocity Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 37 | 76 | 32 | 16 |

| 2025 | 68 | 81 | 43 | 14 |

Look at that. Webb’s pitch type probability percentile shot up. Naturally, this is the arsenal metric that requires a bit more explanation. Pitch type probability is “the probability the batter would be able to correctly identify the incoming pitch type given the release point, the pitch’s trajectory up to the batter’s decision point, and the count in which it was thrown,” per Sutton-Brown’s primer. In other words, it measures a pitcher’s ability to confound a batter’s expectations or otherwise keep him guessing. A higher pitch type probability means more uncertainty for the hitter. Webb was below average in that metric last year, and it wasn’t hard to see why. Now he’s in the top third of the league, and his surprise factor and movement spread are trending upward as well. His velocity spread didn’t move – the cutter sits in the middle of the speeds of the pitches he’d thrown in prior years – but adding a cutter and using more four-seamers has changed everything else.

Webb hasn’t thrown a ton of cutters to righty hitters this year, and I understand why. His sinker is borderline unbeatable for righties. They make poor swing decisions against the pitch and also hit it on the ground two thirds of the time that they put it in play, an enviably high number. His sweeper misses bats and coaxes weak contact when righties offer at it; it’s breaking away while they look for sinkers, which makes for uncomfortable, lunging swings against it. He even has good enough command of his changeup to bury it in advantageous counts.

Another way of thinking about this: Before 2025, Webb had the tools to beat righties; sinkers and sweepers thrown by right-handed pitchers are tremendously effective against right-handed hitters. However, he wasn’t playing with a full deck without the platoon advantage; his best two pitches are less effective against opposite-handed hitters. To neutralize that disadvantage, he needed something that fit in between the movement profiles of the rest of his offerings. So he added a cutter, and now he’s two different pitchers depending on whether he’s facing a righty or a lefty.

Webb hasn’t displayed an anomalous platoon split in his major league career; he’s been roughly league average, in fact. But it always felt like it should’ve been worse, and either way, it couldn’t hurt for his platoon split to get better. “Just add a cutter” might be an over-prescribed solution, but for Webb, it appears to be just the ticket. So, sorry to batters across the country; one of the best pitchers in baseball just got measurably better by adding a pitch that doesn’t even look very good. The game is unfair sometimes.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Very cool! This seems to be the same general strategy Hunter Brown took at Bregman’s advice. If you have a pitch that goes one way, add a similar one that goes the other way.

It seems like the emphasis on pitch metrics had scared pitchers from using otherwise (in a vacuum) poor or average pitches in deference to 2 pitches one can nearly perfect, but now we are returning to the old school approach of using multiple pitches off each other. Metrics+experience is going to prove a deadly combination.