You Can’t Square Up Andrew Abbott

The Reds rotation has been an undeniable strength this season. The team’s starters are third in park- and league-adjusted ERA, and their collective peripherals mostly back it up; they’re 10th in park- and league-adjusted FIP. Hunter Greene has been phenomenal, Nick Lodolo has made some key command improvements, and Brady Singer has added a secret ingredient, though his ERA has ballooned to over 5.00 since Michael Baumann wrote about him last month. But the pitcher leading the team in ERA is Andrew Abbott, and before Baumann can write about his third Cincinnati starter this year, I’d like to take a stab at puzzling out what’s gone right for the 25-year-old lefty.

What if I told you that while Abbott’s fastball is coming in about a tick slower than normal and his arm slot is five degrees higher than usual, he has somehow managed to slightly improve the pitch’s Stuff+ score? You might be a bit confused, as the trend for many pitchers has been to try and lower their arm slot in an effort to flatten out their four-seamers. A flatter approach angle often leads to more swings and misses at the top of the zone and weaker contact, as batters have trouble squaring up a pitch that looks like it’s rising above their bat. Abbott has always had a high release point, but his 50 degree arm angle is now the 11th-highest arm slot among qualified left-handed pitchers.

Research into the relationship between a pitcher’s arm slot and the shape of their pitches has shown that as a pitcher’s arm slot rises, they’re able to generate more backspin. More backspin allows them to create more induced vertical break (IVB). Put simply, IVB is a function of arm angle. The other thing about a high arm angle is that purer backspin fastballs tend to cut less horizontally. Abbott has managed something somewhat tricky with his new arm slot:

| Year | Velocity | Arm Angle | Vertical Release Angle | Vertical IVB | Horizontal Break | Vertical Approach Angle Above Average | Average Vertical Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 92.7 | 45.8° | -1.9° | 16.3 | 7.8 | +0.18° | 2.79 |

| 2024 | 92.8 | 44.9° | -1.9° | 16.3 | 8.9 | +0.06° | 2.80 |

| 2025 | 91.8 | 49.5° | -2.2° | 16.4 | 8.5 | -0.21° | 2.67 |

Despite the higher release angle, Abbott hasn’t experienced a corresponding increase in the amount of carry on his heater. The other odd thing is that he’s been able to maintain the higher-than-normal horizontal break he generates with the pitch. Because he’s now throwing from a higher slot, the pitch has a much steeper approach angle, and the pitch’s cutter-esque shape provides a wider horizontal approach angle.

Abbott’s four-seamer now stands out both because it doesn’t carry as much and because it cuts more than you’d expect. A “dead zone” fastball describes a pitch with unspectacular movement traits — a fastball that moves as expected. Research has shown that a fastball’s dead zone is a function of the pitcher’s arm angle, leading to the concept of a dynamic dead zone (DDZ). Using Alex Chamberlain’s calculated DDZ deltas (based on work done by Max Bay), we can see just how much Abbott’s fastball falls outside of what the batter expects based on his arm slot:

| Year | Vertical Dead Zone Delta | Horizontal Dead Zone Delta |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | +0.2 | +1.4 |

| 2024 | -0.4 | +1.8 |

| 2025 | -0.4 | +2.8 |

Remember, magnitude is what matters when evaluating a pitcher’s DDZ, so Abbott’s negative vertical dead zone delta isn’t necessarily a bad thing, though his +2.8 horizontal dead zone delta is very much a good thing.

The results have been positive so far. His whiff rate on the pitch has improved from just over 19% during his first two seasons to 25.2% this year. The additional swings and misses are nice, but he’s also turned his heater into a contact-suppression monster. Just look at some of these key contact metrics from Statcast:

| Year | Whiff% | xwOBAcon | Hard Hit% | Barrel% | Squared Up% / Swing | Blast% / Swing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 19.80% | 0.447 | 51.0% | 12.6% | 24.3% | 11.8% |

| 2024 | 19.40% | 0.395 | 43.2% | 11.3% | 25.5% | 9.4% |

| 2025 | 25.20% | 0.297 | 26.7% | 8.9% | 16.3% | 4.9% |

Abbott’s expected wOBA on contact when he throws his fastball is just .297, 17th among the 248 pitchers who have thrown at least 100 four-seamers this year. The hard-hit and barrel rates against the pitch are miniscule. The most impressive aspect of his contact management comes from Statcast’s new bat tracking data. Opposing batters produce the second-highest average bat speed in baseball against Abbott’s fastball, but they “square-up” the pitch at the third-lowest rate on a per swing basis and they produce a “blast” against his heater at the fourth-lowest rate in baseball. In other words, batters really gear up when they see Abbott’s fastball because their eyes are telling them that the pitch is very hittable, but they simply cannot make solid contact against it.

To connect this all back to the pitch’s shape, I expect that this contact suppression is all linked to the amount of horizontal break Abbott generates with his fastball. With his high arm slot, a batter expects to see a straight four-seamer with tons of carry. Instead, they’re presented with a cutting fastball that doesn’t have as much carry as you’d expect. Rather than swing completely under the pitch like they might if it had a ton of carry, they’ll often put it in play, but it’s weak contact because the pitch doesn’t come in where they expect it to horizontally. So much of the contact he generates with the pitch is off the end of the bat or in on the handle, leading to weak fly balls and popups.

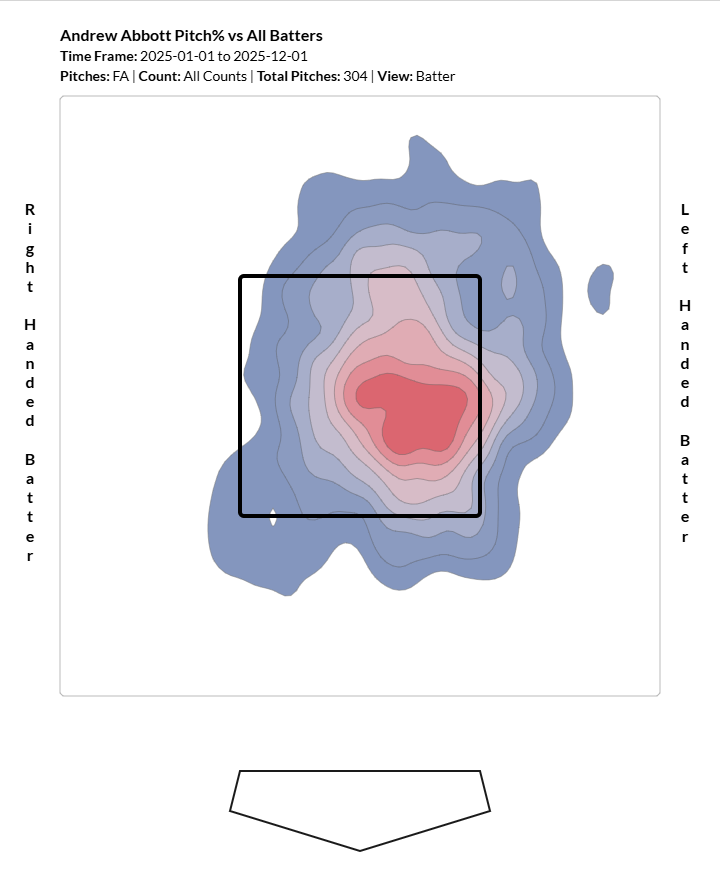

Of course, location matters, too. In the first table above, I included average vertical location, because location is a critical component of vertical approach angle. Abbott is locating his fastball much lower in the strike zone this year, which, along with his higher arm slot, has contributed to his steeper approach angle. He’s also been very consistent with his location on the outer half of the plate to right-handed batters:

Because the horizontal break on the pitch causes it to tail away from righties, his location is perfect for inducing weak contact off the end of the bat while avoiding the barrel if it ends up over the heart of the plate.

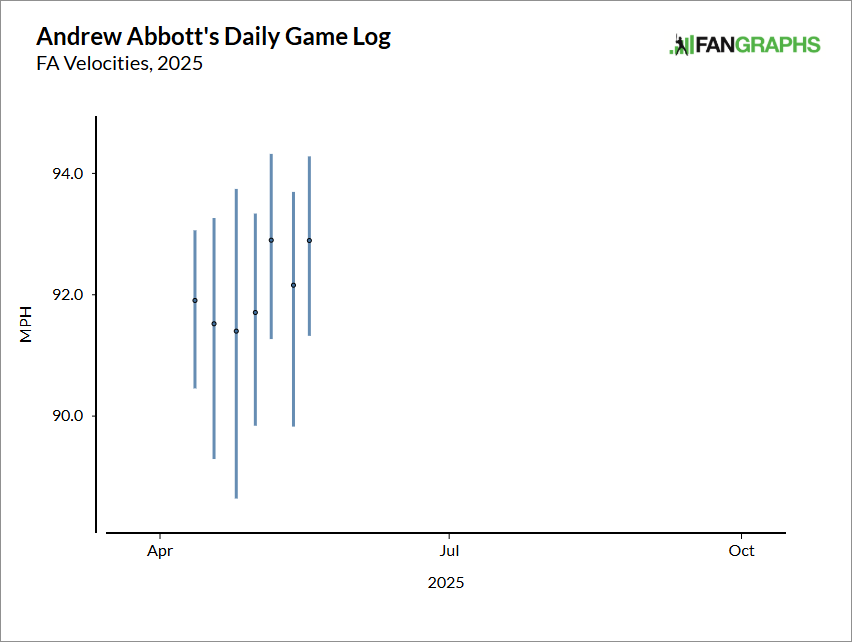

In case you were worried about Abbott’s dip in velocity, I’m happy to report that his heater has had a bit more zip during his last few starts:

A shoulder injury last August cut short his 2024 season, and he entered spring training a little bit behind schedule because of it. I suspect that he was still ramping up during his first few starts of the season and that his velocity will be back to normal moving forward.

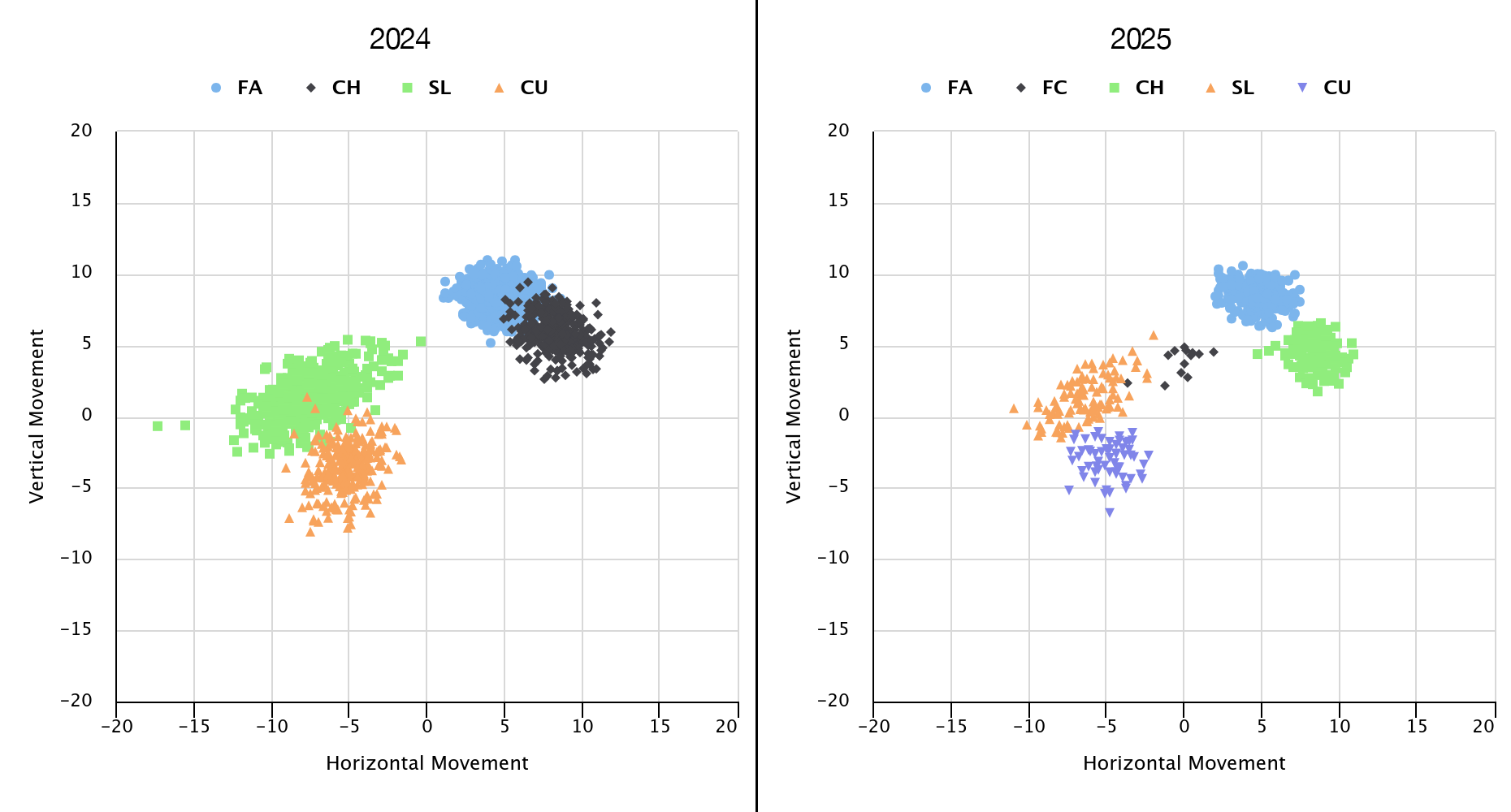

Beyond his fastball and the new arm slot, there’s one key change to the rest of Abbott’s repertoire that could be contributing to his success. He’s getting about three more inches of drop on his changeup while still maintaining the pitch’s above-average horizontal break. The whiff rate on that pitch has improved by about four points, and the expected wOBA against it is just .222. More importantly, the change in shape has allowed him to differentiate the pitch from his fastball a bit more:

Please excuse the color differences from year to year in the plots above. In Abbott’s pitch plot from 2024 on the left, his changeup (the black blob) somewhat overlaps with his fastball (the blue blob). In 2025, on the right, his offspeed pitch (the green blog) is wholly distinct from his heater (the blue blob).

Abbott briefly discussed the evolution of the pitch with Charlie Goldsmith of the Dayton Daily News in late April:

It’s come a long way. I talked with Nick Martinez and a bunch of the guys about how to throw it, grips and all of that stuff. It’s finally coming around. It’s not to where I think it can be yet, but it’s gotten a lot more consistent.

He has increased his use of his changeup from 16.3% last year to 21.3% this year, and it has proven to be a potent weapon against right-handed batters.

With a new arm slot, a deceptive fastball, and an improved changeup in hand, Abbott has truly elevated his arsenal. His walk rate is a little high right now, but his strikeout rate is 30.3%, and the contact suppression improvements he’s made to his heater have almost entirely negated those additional free passes. The top-line results certainly speak for themselves: Abbott has allowed more than one run in just one of his starts this year, and that happened to be the only start in which he’s allowed more than four hits. As long as batters are unable to square up his fastball, we could be seeing a significant step forward from the young lefty.

Jake Mailhot is a contributor to FanGraphs. A long-suffering Mariners fan, he also writes about them for Lookout Landing. Follow him on BlueSky @jakemailhot.

Jake and Ben going back to back on phenomenal articles.

Come to think of it, it’s been a tremendous season on Fangraphs. I think I’m going to bump up my monthly donation.

Thanks!