Your Final Pre-Robo-Zone Umpire Accuracy Update

For four years now, I’ve been updating you on the changing contours of the strike zone. By my count, this is the 10th installment in that series and the sixth specifically about the accuracy of ball-strike calls on the edges of the zone. With the implementation of the ABS challenge system in 2026, these updates will no doubt start to look a bit different. This is our last umpire accuracy update of the pre-ABS era, so let’s take stock of where we are at the end.

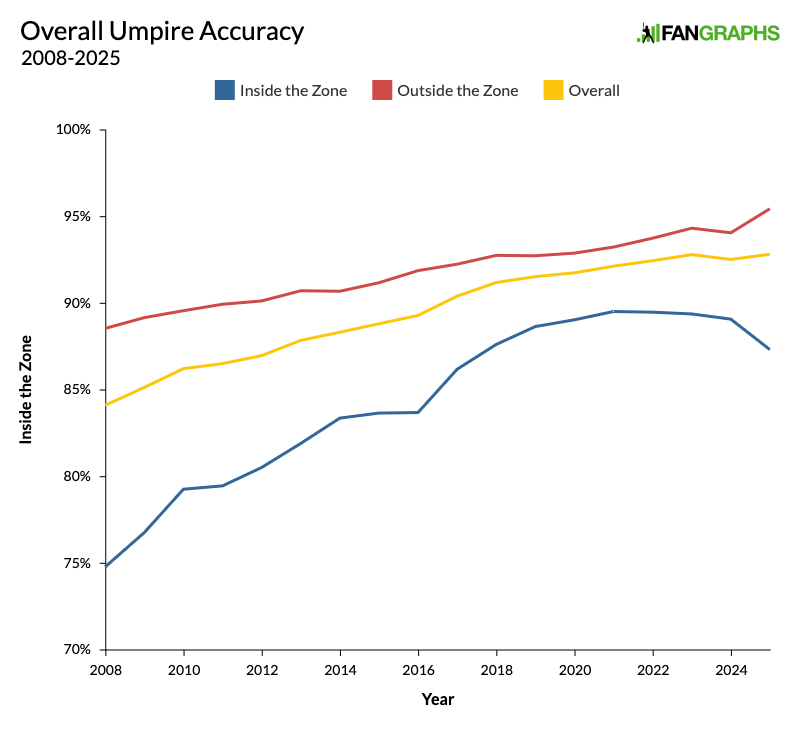

After a tiny dip in 2024, umpires were back on track in 2025, posting a record-high accuracy rate of 92.83% overall. In fact, 2024 was the only year in the pitch-tracking era in which umpires didn’t set a record for accuracy. However, this latest record came with a bit of controversy. Early in the season, pitchers and catchers picked up on the fact that the strike zone seemed to have shrunk. The league tightened up the standards that it used to grade umpires, reducing the size of the buffer zone around the edges of the zone. As a result, accuracy shot up specifically on pitches outside the zone, even more specifically, on pitches just above the top of the zone, causing pitchers and catchers to complain that they were losing the high strike.

This graph reminds us of a couple facts that might just be so obvious that we rarely think about them. First, the vast majority of takes come on pitches outside the strike zone. Of course they do; those are the pitches you’re not supposed to swing at. This year, for example, 68% of the calls umpires had to make came on pitches outside the strike zone. Second, it’s easier to identify balls than it is to identify strikes. Of course it is; the area outside the zone is a lot bigger than the area inside the zone.

Those facts lead us in two slightly contradictory directions. First, most of the catching up that umpires have done over the past couple of decades has had to come on pitches inside the zone, which meant calling more strikes. They started out with much more room for improvement there. From 2008 to 2025, they added 13 percentage points to their accuracy inside the zone and seven points outside the zone. Second, because most takes come on balls, the safest way to improve your accuracy overall is to improve at calling pitches outside the zone, which means calling more balls. Right around 2021, umpires seemed to find their level. Instead of plateauing, they kept improving by calling more balls both inside and outside the strike zone. As overall accuracy kept improving, accuracy inside the zone fell in each of the past four seasons. It took its biggest dip by far in 2025, falling by 1.7 percentage points. That dynamic is even more apparent when you look only at pitches in the shadow zone, the area one baseball’s width from the edge of the zone on either side.

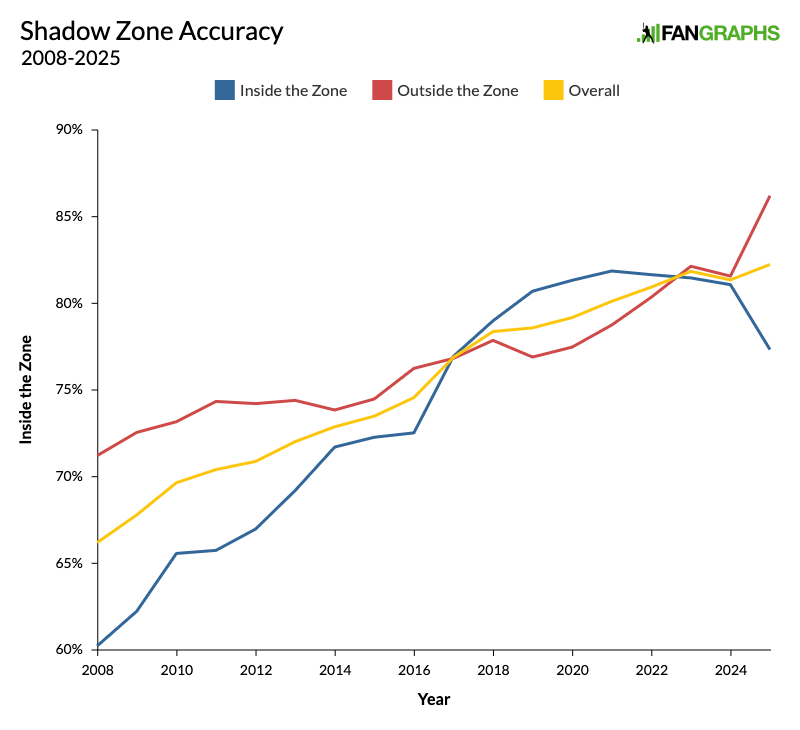

Back when this controversy reared its head in May, I ran a similar graph, but the departure in 2025 on this graph is slightly more extreme, because that trend toward calling more balls increased as the season went on. At the beginning of the pitch tracking era, the edges of the zone were much more permeable in both directions, but umpires were much better at identifying balls than strikes. They closed that gap by 2017 and kept on going, running better rates on pitches that just clipped the zone than the ones that just missed it. But that only lasted for a few years. In 2023 and 2024, they ran nearly identical accuracy rates on those borderline pitches. It was fair to assume that maybe we’d reached the limit of how good the human eye can be at identifying whether or not pitches clipped the edges of an invisible rectangle. That assumption is still in play because of the way the improvement went down in 2025. Even on those closer takes in the shadow zone, there’s still more area outside the zone than inside it, and 55% of the calls umpires have to make are on pitches outside the zone. Calling a more accurate zone overall meant calling more balls and missing more strikes.

Obviously, that trend can’t continue forever. That yellow line only ticked up ever so slightly in 2025; if umpires were to err any further in favor of calling balls, it would start heading back down. If we weren’t heading toward a challenge system, I’d be really interested to see what would happen next. Would tightening up the zone continue to result in more balls and fewer strikes, even to the point where umpires became less accurate? Or would this new grading system eventually improve accuracy on both as umpires continued to get used to it?

We may still get the answers to these questions, because the ABS challenge system won’t be nearly as disruptive as you might assume. Baseball Savant’s minor league search function tells us that in 2025, even with the challenge system, minor league umpires were more accurate than their major league counterparts by just 0.3 percentage points, leading 93.1% to 92.8%. But those numbers don’t say exactly what you think they say.

According to an excellent explainer from JJ Cooper of Baseball America, Triple-A saw approximately four challenges per game in 2025, and 50% of them were successful. It’s reasonable to assume that major leaguers will be at least a little bit better at picking their spots for challenges. According to Anthony Castrovince of MLB.com, during the spring training test drive of the system, 52.2% of challenges overturned the call in question. Let’s assume those rates will hold and apply them to the 2025 numbers. That would cut out 5,074 missed calls, raising the overall accuracy from 92.8% to 94.2%. On a per-game basis, that would drop the number of misses from 10.9 to 8.8. The challenge system will overturn 2.1 missed calls per game, but that’s only if the numbers hold. They might not.

Outside the shadow zone, minor league umpires were right 99.71% of the time. This number was undoubtedly boosted by the challenge system. They missed just 838 times all season long, and as most of those misses came after the fifth inning, I would further assume that often enough, those misses came after the wronged team had already exhausted their challenges. In the majors, even without a challenge system, umpires got 99.73% of calls outside the shadow zone right, slightly better than their minor league counterparts. In 2025, they missed just once every four games, but because those calls are the most egregious, they’re the ones we remember most clearly. The challenge system will likely bring that number even lower, but they’re starting from a very high place.

The gap is bigger inside the shadow zone, where major league umpires led minor league umpires in accuracy, 82.2% to 81.6%. At this point you may be wondering how minor league umpires could have been more accurate overall if they were worse both inside and outside the shadow zone. The reason the numbers work out is that, as you’d expect, minor league pitchers have worse control, which leads them to hit the edges of the zone less frequently. Major league pitchers hit the shadow zone 39.5% of the time, while minor leaguers hit it 36.4% of the time. So minor league umpires were able to pump up their overall accuracy rate by seeing more of the easier, non-shadow zone calls. This also means that in the minors, a higher percentage of challenges were wasted on calls that weren’t particularly close. The challenges in the majors may well come on closer pitches, which could mean a downtick in the overturn rate. That number I quoted earlier, 2.1 overturned calls a game, could well be too high. If you ever saw an outrageous missed call and remarked that it would’ve been called correctly in a Triple-A game, don’t be so sure. This year, major league umpires were more accurate even without the help of ABS. They’re already pretty good.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

When this buffer zone news broke, I made the point that the bigger change wasn’t the shrinking of the size of the buffer — it was that the buffer went from being added solely to the outside of the zone to “straddling” the zone line.

Functionally, this means umpires lost 1.25″ of grace outside the zone and gained 0.75″ of grace inside the zone.

If I’m unsure, I should now default to calling it a ball. Before, you could never get a “close enough” exemption if you called ball — you were either right or wrong. So call it a strike. But now, since I get that space inside the zone to call balls and have it be “close enough”, the concept that Davy outlines here (the entire universe except for that (17″ x zone height) box is a ball, so it’s exceedingly more likely you’d be right if you blindly called ball every time).

As a fan, I am most satisfied not necessarily with the absolute position of those three lines, but that they converge — I would rather umpires be 80% right but 80% right in the zone and 80% out of the zone than being 85% right but 80% right in the zone and 90% right outside of the zone (or vice versa). Those numbers are provided for example, not as any specific target.