You’re Probably Underrating Yordan Alvarez

Quick: Who are the best five hitters in baseball this year? Take a quick gander at the leaderboards, if you’d like, before answering. There’s the WAR leaderboard:

| Player | wRC+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|

| Mike Trout | 179 | 8.6 |

| Christian Yelich | 173 | 7.7 |

| Cody Bellinger | 163 | 7.1 |

| Alex Bregman | 163 | 7.1 |

| Ketel Marte | 150 | 6.9 |

| Anthony Rendon | 160 | 6.8 |

| Marcus Semien | 132 | 6.4 |

| Mookie Betts | 134 | 6.2 |

| Xander Bogaerts | 140 | 6.2 |

| George Springer | 158 | 6.0 |

That’s not what you want, though, because defense gets involved there. How about a wRC+ leaderboard instead? That should keep the Xander Bogaerts’s and Marcus Semien’s of the world from intruding on our hitting party:

| Player | wRC+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|

| Mike Trout | 179 | 8.6 |

| Christian Yelich | 173 | 7.7 |

| Alex Bregman | 163 | 7.1 |

| Cody Bellinger | 163 | 7.1 |

| Anthony Rendon | 160 | 6.8 |

| George Springer | 158 | 6 |

| Nelson Cruz | 157 | 3.5 |

| Ketel Marte | 150 | 6.9 |

| Juan Soto | 148 | 4.9 |

| Pete Alonso | 147 | 4.6 |

Trout, Yelich, Bregman, Bellinger, and Rendon. That’s a pretty solid five. It’s also missing an obvious name: Yordan Alvarez, quite possibly the best hitter in baseball this year.

Why isn’t Alvarez on the list? It comes down to the tyranny of the qualified hitter. Setting a plate appearance minimum is a reasonable idea: without it, the best wRC+ this year would belong to Oliver Drake, who singled in his only plate appearance. No one wants that, except perhaps Oliver Drake.

That doesn’t mean that it’s always right to ignore everyone who falls short of the qualification minimum, though. Alvarez has 320 plate appearances this year, a far cry from Drake territory. Because he wasn’t called up until June, he won’t qualify for the batting title this year, but that shouldn’t distract you from the fact that he’s one of the best hitters in the major leagues, full stop.

I won’t belabor the Yordan Alvarez origin story, because it’s been told many times. He was signed by the Dodgers, traded to the Astros for Josh Fields, and hit a ton at every stop in the minors, finally forcing his way to the majors by hitting a dizzying .343/.443/.742 in Triple-A this year. That’s the past — the present is essentially all home runs and doubles.

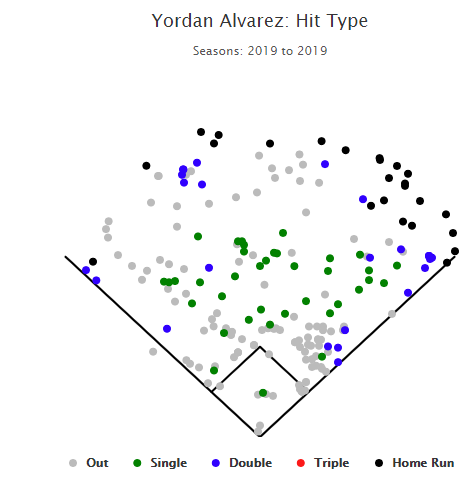

When Alvarez came up, Dan Szymborski lauded his all-fields power. He hit more home runs and more doubles to left field than to right in the minors this year, and combining that huge natural power with Minute Maid’s short porch in left felt like it might be borderline unfair. That hasn’t happened at all, as this spray chart attests:

In fact, he’s visited the Crawford Boxes only once, on this harmless-looking swing:

Rather than using left field, Alvarez has tapped into his power by doing damage on the pull side. Pulled line drives and fly balls are the most valuable batted ball type in baseball, and Alvarez is a standout even given that high baseline. He has the fifth-highest hard-hit rate on pulled balls in the air, and that might undersell the amount of damage he’s doing.

Here’s a random, tossed-off statistic for you. When Alvarez pulls the ball in the air, he bats .868 with a 2.421 slugging percentage. Percentage doesn’t make much sense for a number like 2.421, but nothing about Alvarez’s production does. That’s good for a 768 wRC+, best in the majors by 103 points. As I mentioned, production is high across baseball on pulled air balls, but not like this; the league as a whole has a 384 wRC+, with an OPS lower than Alvarez’s slugging percentage.

Your mind will logically go to small sample sizes and regression here, and that’s not unreasonable. Consider this, though: Alvarez’s xwOBA is a robust .963 on these balls, second only to Joey Gallo. He hits them, on average, 100.3 mph, good for sixth in the league. He’s barreling up nearly half of them, 43.2%. In other words, Alvarez might be getting marginally lucky when he pulls the ball in the air, but for the most part he’s hitting the ball too hard to need luck.

About the only negative thing you can say about Alvarez is that he hasn’t tapped into the pull side as often as would be optimal. For the season, he’s pulling 31.7% of the balls he puts in the air, higher than the major league average of 29.8% but only in the 62nd percentile among all batters. For someone with so much raw power, he still has room to optimize his swing to get to it more often, a scary thought for someone with a 177 wRC+ already.

Even without more pulled balls, however, Alvarez deserves his gaudy statistics. Earlier this summer, I looked into expected home run totals based on exit velocity. Alvarez has turned 30% of his 15-45 degree launch angle hits into home runs, far higher than the big league average of 15% (the number diverges slightly from HR/FB rate due to slightly different balls being included). It’s not luck, though — based on how hard he’s hit them, he should be turning nearly 27% of them into home runs. That 3% divergence is tiny, amounting to just over two home runs, which means that he’s earned the vast majority of his dingers.

By now, I’ve probably painted a picture in your mind. Alvarez is the second coming of Joey Gallo, a slugger so powerful that he destroys everything he hits. He gets the ball in the air more than average, pulls it more than average when he gets it there, and has power to all fields in addition to the hilariously over-the-top pull power.

But if that’s how you picture Alvarez, as the most recent incarnation of Dave Kingman or Joey Gallo, you’ve left something out. Alvarez has the raw power of those guys, but he’s getting to all that pop without the tradeoffs they have to make. Gallo broke out this year by getting his swinging strike rate down to a still-awful 16.2%, a sizable improvement from the near-20% rate from his career before 2019. Nelson Cruz, a more reasonable sort of slugger than Gallo, comes up empty on more than 13% of pitches. Not Alvarez — he’s running a 10.4% swinging strike rate, better than league average.

Think about that for a second. The player with arguably the most power in the major leagues has a lower swinging strike rate than Jeff McNeil, king of batting average. He accomplishes this by making an average amount of contact and having a roughly average batting eye. When you hit the ball as hard as Alvarez does, that’s all you need, because pitchers will stay away from you as much as possible — he has a 15th-percentile zone rate, as befits someone of his extreme power.

In this recent era of superstars and home runs, it’s easy to gloss over the fact that Alvarez combines better-than-average plate discipline with otherworldly power. Mike Trout and recent-vintage Christian Yelich have normalized combining awesome power with enviable batting eyes, but it’s simply not that common. What’s more, Alvarez is 22, and he’s only four days away from this being his age 21 season, as he was born on June 27th.

Even at 22, though, Alvarez is in near-uncharted territory. He has a K-BB% four points better than league average and an ISO 88% better than league average. Since 1970, how many players have had better-than-average K-BB% and ISO’s at least 50% higher than league average by age 22, using a 300 PA minimum? Exactly 17, and that 17 is a nice list to be on:

| Player | Year | Age | K%-BB% | ISO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yordan Alvarez | 2019 | 22 | 11.3% | .344 |

| Bryce Harper | 2015 | 22 | 1.1% | .319 |

| Albert Pujols | 2001 | 21 | 3.5% | .281 |

| Juan Soto | 2019 | 20 | 4.6% | .279 |

| Alex Rodriguez | 1996 | 20 | 6.6% | .272 |

| Albert Pujols | 2002 | 22 | -0.4% | .247 |

| Mike Trout | 2012 | 20 | 11.3% | .238 |

| Mike Trout | 2013 | 21 | 3.6% | .234 |

| Carlos Correa | 2015 | 20 | 8.8% | .232 |

| Jack Clark | 1978 | 22 | 3.3% | .231 |

| Barry Bonds | 1987 | 22 | 5.6% | .230 |

| Ken Griffey Jr. | 1992 | 22 | 3.7% | .226 |

| Cesar Cedeno | 1972 | 21 | 1.0% | .216 |

| Jeff Burroughs | 1973 | 22 | 3.5% | .207 |

| Ken Griffey Jr. | 1991 | 21 | 1.7% | .201 |

| Eddie Murray | 1978 | 22 | 3.9% | .195 |

| John Milner | 1972 | 22 | 5.4% | .185 |

Raise the minimum for ISO to 75% better than league average, and that list drops to five. You know Ken Griffey Jr. and Bryce Harper, but Jack Clark and Cesar Cedeno had monster seasons as well. Cedeno was one of the best players in baseball when he first came up. From 1972, his age 21 season, to 1977, he averaged 5.5 WAR a year. His 1972 season in particular was a masterpiece, a 7.8 WAR gem with solid defense and a 163 wRC+.

Alvarez can’t match the defense, but he’s an even more fearsome hitter. You’ve probably heard of the only batters to record a higher wRC+ at age 22 or younger:

| Player | Year | wRC+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ted Williams | 1941 | 221 | 11.0 |

| Bryce Harper | 2015 | 197 | 9.3 |

| Ty Cobb | 1909 | 188 | 9.7 |

| Joe Jackson | 1912 | 186 | 9.1 |

| Joe Jackson | 1911 | 184 | 9.3 |

| Stan Musial | 1943 | 180 | 9.9 |

| Yordan Alvarez | 2019 | 177 | 3.3 |

Though Alvarez doesn’t have the full-season batting line or defensive value to have historically great counting numbers, his expected stats don’t exactly tell a story of regression. He has the sixth-highest xwOBA in baseball, the fifth-highest xSLG, and even the 21st-highest xBA. He’s eighth in barrels per batted ball, fifth in barrels per plate appearance, and has the eighth-highest maximum exit velocity in baseball despite not having a full season of plate appearances. There’s no number that doesn’t support his status as an elite hitter.

Alvarez will almost certainly win the AL Rookie of the Year Award. He’s not some completely undiscovered gem toiling in anonymity. People think of him as a pretty good rookie, though, not one of the best young hitters of all time. Why is that, when he has the statistics to enter the discussion? It’s the tyranny of the qualified filter. Let it go, though, and focus on the sheer mastery we’re seeing. Yordan Alvarez is putting up one of the best young hitting seasons of all time. Don’t discount it just because he didn’t manage 3.1 plate appearances per Astros game.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Oliver Drake the god

Great piece, Ben

Johnny Davis has a higher wRC+. (As of tonight.)