Zack Wheeler Keeps Quietly Improving

Zack Wheeler signed a big contract before the 2020 season, and if we’re being honest, the Phillies paid for potential. That’s not to say Wheeler wasn’t an effective starter with the Mets, but his career numbers — a 3.77 ERA, a 3.71 FIP, a 22.8% strikeout rate, and an 8.5% walk rate — didn’t scream ace.

His stuff, on the other hand, spoke loudly. An upper-90s fastball and lower-90s slider invite comparisons with Jacob deGrom, and his curveball prevents batters from sitting on a single breaking ball. If you could design a pitcher in a lab — well, fine, you might come up with deGrom or Gerrit Cole. But if you ended up with Wheeler, you’d certainly be happy with your work.

When a pitcher’s results — and again, they were good results — fall short of what you’d expect from their stuff, any stretch of better outcomes feels like a tantalizing glimpse at what a breakthrough might look like. At this point, however, it’s not a glimpse: Wheeler has fully broken out into the ace the Phillies hoped for when they signed him.

Consider this: since leaving the Mets, Wheeler has the 10th-best ERA in baseball. It’s not some fluky sequencing effect, either. He has the eighth-best FIP in the game over that time frame, the 17th-best xFIP, and the 17th-best SIERA, another advanced ERA estimator. He’s done all of that while throwing the third-most innings in the game, behind only Shane Bieber and Aaron Civale. That combination of skill and volume puts him sixth among all starters in WAR over that time frame, in a virtual tie with Cole.

Here’s the wild part: even those stats undersell what Wheeler is doing right now. He’s kicked his game up a notch this year, basically across the board — more strikeouts, fewer walks, and the best run prevention marks of his career in literally every category. If it weren’t for his old teammate in Queens, we’d be talking about Wheeler as a Cy Young frontrunner. Let’s delve into what’s new, what’s the same, and what we can expect going forward.

To explain Wheeler’s new status as a strikeout artist, let’s talk about the anatomy of a strikeout. There are two key points in an at-bat for strikeouts: what happens on the first pitch, and what happens with two strikes. Wheeler has always been good at getting ahead in the count, and this year has been no exception.

How? He’s throwing pitches in the strike zone 53.6% of the time, marginally above average. More importantly, he’s doing that without allowing too much loud contact. First strike percentage as commonly reported is actually a misnomer. It’s calculated as strikes plus balls in play, so you could theoretically run a great first strike percentage by lobbing a batting practice fastball down main street and letting hitters tee off.

Hitters aren’t letting first pitches go by the way they used to, not from Wheeler or anyone else. They’re swinging at a third of Wheeler’s initial offerings (league average is around 28%), cognizant of the fact that he throws plenty of strikes. They’ve barreled up six pitches already, getting two home runs in the bargain. But they’re also getting behind in the count quite a bit; 52% of the time, they end up down 0-1, as compared up 1-0 only 35% of the time. That means Wheeler is starting out in an advantageous position quite often without paying a huge price in contact — batters are putting Wheeler’s first pitch into play at a roughly average rate.

Getting ahead in the count matters so much. Batters hit .210/.256/.338 after starting out down 0-1, a measly .261 wOBA. When they start out ahead 1-0, they check in at .248/.376/.428, a .353 wOBA. That’s the difference between Evan Longoria (fully rejuvenated, read all about it) and Myles Straw, who’s hitting so poorly that his job may be in danger.

This first-pitch prowess doesn’t explain Wheeler’s new form, because he’s always been good at getting ahead. That should come as no surprise: in the last four years, he’s running a sterling 6.4% walk rate, and you can’t do that without making it easy on yourself by starting at-bats with a strike.

After the 2019 season, I wrote about what Wheeler could do to improve his strikeout rate. I focused on his two-strike approach, which seemed suboptimal for someone with his stuff. That year, a whopping 26.2% of the pitches he threw with two strikes were sinkers. Not all fastballs, mind you — that would be a low number of fastballs — but specifically the sinker, the most contact-friendly pitch in his arsenal.

Batters don’t miss Wheeler’s sinker, because they basically don’t miss anyone’s sinker. Over the course of his career, they’ve come up empty on only 14.8% of their swings against it. In that 2019 season, only 18.3% of the two-strike sinkers he threw resulted in strikeouts — and only 16.5% of the two-strike sinkers he’s thrown in his career have. That’s a poor putaway rate; the league average sits at 20.9%, and Wheeler is an elite pitcher; he should be far better than league average, not below it.

As I mentioned above, Wheeler used to throw sinkers more than a quarter of the time with two strikes. In 2020, that number dropped a bit, to 20%. This year, he’s down to 13%, a dip that mirrors his decreasing overall sinker usage. Given the rest of his arsenal — he throws a four-seamer, a slider, a curveball, and even a show-me changeup — a high-contact pitch isn’t helpful, particularly in two-strike counts, so the change makes plenty of sense.

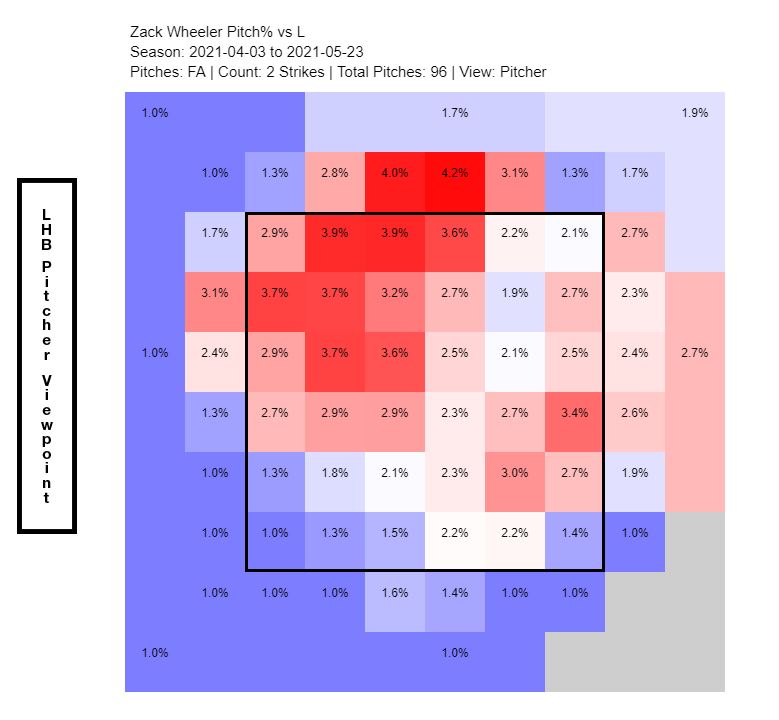

In its place, Wheeler has increasingly turned to his four-seam fastball. Using 2019 as a benchmark again, he went to the high heat 29.7% of the time with two strikes. This year, he’s up to 48.8%, and a whopping 55.7% of the time against lefties (40% against righties). Good luck dealing with 97 and this location, lefties:

In addition to re-allocating his fastballs from sinking to rising, Wheeler is increasingly using his slider to attack lefties. That’s in line with a broad, league-wide trend in favor of sliders to opposite-handed batters, and Wheeler is also doing something clever: he’s taking advantage of the pitch’s shape and his ability to command it, targeting the outside corner against hitters trying to avoid chasing. This pitch was borderline, but good enough to get Brandon Belt:

And after you know that an outside-corner snipe is possible, you have to respect that pitch. Juan Soto rarely looks foolish, but he rarely faces a well-located 91 mph slider:

Oh, yeah: Wheeler has a nice curveball, too. He’s adept at snapping it off for a bounced, chase-inducing nightmare. Thanks for playing, Justin Williams:

Or hey, if the hitter decides to lay off, he can go full Adam Wainwright mode too:

That curveball has been lethal this year; it sports a 40% putaway percentage, tied with Corbin Burnes for the best mark on a curveball. One reason why: the curve looks a lot like his four-seam fastball out of his hand, and given his still-high fastball rate with two strikes, batters can’t sleep on that pitch. By excising the sinker, he’s increased the difficulty level for hitters: you’ll have to cover high and low, and if you do that, he might dot the outside corner with a slider or victimize righties with a low-and-away version of the pitch.

Is Wheeler’s transformation really as simple as getting rid of more batters after reaching two strikes? I mean… pretty much? Wheeler has never had any trouble reaching two strikes; he’s gotten to two-strike counts 148 times this year already, the seventh-best mark in the league. Now, he’s upped his strikeout rates in every single two-strike count:

| Count | 2013-2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| 0-2 | 46.9% | 50.9% |

| 1-2 | 42.0% | 55.3% |

| 2-2 | 35.3% | 46.1% |

| 3-2 | 25.5% | 37.9% |

To be clear, this isn’t the only thing Wheeler has improved upon this year. He’s running a career-low walk rate at 5.3%. He’s running a career-high swinging strike rate in two-strike counts, sure — a juicy 17%. But he’s also running a career-high swinging strike rate in all other counts (12.2%). He’s simply missing more bats, period. And here’s a neat trick: he’s throwing each of his four main pitches faster than he has in every previous year, and posting career-high swinging strike rates on each of them.

Given all of Wheeler’s superlatives, I expected to see a huge uptick in his shadow zone rate, the frequency with which he spots the very fringes of the strike zone and the area just outside of it. But uh, nope:

| Year | Shadow% | 2-Strike Shadow% |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 45.2% | 42.6% |

| 2018 | 44.4% | 41.9% |

| 2019 | 45.3% | 45.7% |

| 2020 | 44.4% | 43.2% |

| 2021 | 44.6% | 44.4% |

I’m not going to lie to you: I’m pretty happy that Wheeler didn’t also magically start hitting the corners more often. Analysis is unsatisfying if the pitcher just magically improves. Hey, did you know that throwing harder and missing more bats by spotting your pitches in better locations is good? If someone just starts hitting every spot, well, congratulations to them, but that’s not particularly interesting to think about.

Wheeler has done his fair share of magical (read: due to extremely hard offseason work) improvement. He’s throwing all of his pitchers harder, after all. But he’s also improved by grabbing the low-hanging fruit — or rather, by not bailing out the low-hanging fruit with a two-strike sinker. Wheeler has always felt this close to dominance. He’s there now, and one of the key drivers has been taking his already wonderful tools and using them more efficiently.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Unfortunately, we’re going to look back on pitchers several years from now and wonder who had the best chemical concoctions rather than just suntan lotion and rosin. I’m not trying to paint Wheeler with that brush, but I am skeptical overall of pitchers whose pitch shapes and spin rates change dramatically… just like I was skeptical when homers were flying over the fence. It’s currently the pitchers’ revenge and everyone is suspect.

Wheeler looks like a different pitcher than his time with the Mets. He used to nibble with two strikes; now he has the confidence to put batters away. The curveball has gone from inconsistent to lethal and a true out-pitch. Clearly, he has the confidence to throw it more often. And I think that is part of what is missing in the discussion of the sticky stuff…. it’s not just the physical impact on the ball, but also on the diverging confidence of the pitcher and the batter.

So, for any pitcher that makes such great advance, we’re left to wonder – how much of that is maturity, how much of that is coaching, and how much of that is sticky stuff? The innocent will seem suspect from time to time and that’s unfortunately, just like it was 20 years ago for batters.

For Wheeler, it ain’t the sticky stuff. His spin rates have been relatively constant:

4-seam fastball spin rate (2017-2021): 2326, 2312, 2341, 2336, 2388.

4-seam fastball velocity (2017-2021): 94.8, 95.8, 96.8, 96.9, 97.2.

The modest increases in spin rate coincide with increases in velocity, which is what you would expect.

I’ve seen Zach Wheeler twice this year, both times when he faced the Braves.

4/3 – 7.0 IP, 1 H, 0 R, 0 BB, 10 SO.

4/9 – 4.2 IP, 7H, 3 R, 3ER, 1 HR, 4 BB, 4 SO.

He’s a slightly better version of the Zach Wheeler I’ve seen before, but that’s pretty much it.