A Suggestion for Vince Velasquez

On April 14, 2016, Vince Velasquez took the mound for his second start as a member of the Phillies, having come over in an offseason trade with the Astros that sent Ken Giles to Houston. In an afternoon matchup against the Padres, he twirled one of the best-pitched games of the last decade, striking out 16 and walking none in a complete game shutout, allowing just three hits to boot. In the last 10 years, just 11 pitchers have struck out 16 or more in a game, and in these 13 performances (Max Scherzer has done it thrice), just five were complete game shutouts. He started his Phillies career on the highest of notes.

Fast forward more than five years, and Velasquez has now signed with those very Padres on a minor league deal in name only. As San Diego desperately tries to find pitching depth to stay afloat in the NL Wild Card race, Velasquez will start on Friday night in a pivotal series against the Cardinals, though he will not be eligible for postseason play if the Padres do secure a spot in October since he signed after the start of September.

The fact that a starting-caliber arm became available in free agency in the middle of the last month of the season tells you two things, both obvious. For the Padres, it shows just how dire their need for pitching is. But I want to focus on the second obvious reality: To get released at this point in the year is proof that Velasquez hasn’t been particularly good. Indeed, in 81.2 innings, he’s posted a 5.95 ERA and 5.59 FIP, production that has been exactly replacement-level.

Velasquez has shown flashes of productivity, but his time with the Phillies ran thin after continually falling short of expectations. In May, Matt Gelb of The Athletic covered what he referred to as the righty’s last stand in Philadelphia and how he hoped to reinvent himself to increase his effectiveness. One thing stood out: He came into this season wanting to mix his pitches more effectively, reflecting on that April 2016 start to explain his change in mindset for 2021.

“Cool, I had 16 strikeouts,” Velasquez said. “But I fucking threw all fastballs. OK, that’s unique. But it’s not part of pitching. It’s not pitching. It’s not sustainable at all.”

As the Padres look to tinker with Velasquez, it is interesting to consider where they may start. Was his plan of throwing fewer fastballs working? Might he have just been choosing the wrong pitches to put in the four-seamer’s place? What is the way forward here?

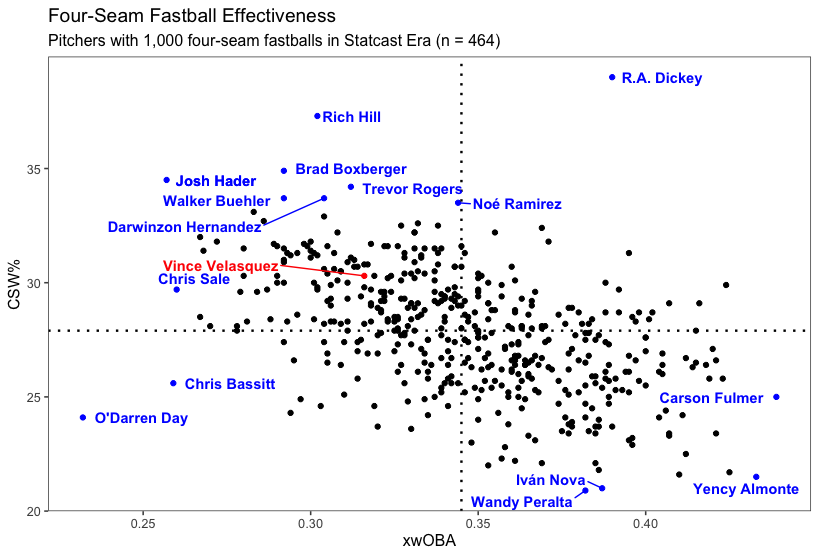

First, we have to discuss that four-seamer. Velasquez’s fastball is, without a doubt, his best pitch. Among pitchers who have thrown at least 1,000 four-seamers in the Statcast Era, he ranks in the 68th percentile in run value per pitch, and among that same group of pitchers, he ranks in the 82nd percentile in CSW% and the 80th percentile in xwOBA allowed. Here is how that compares graphically, with some outliers labeled:

Typically, the best fastballs in baseball belong to relief pitchers, which makes Velasquez’s feat even more impressive. If we limit the data to just starting pitchers, his CSW% and xwOBA allowed jump to the 87th percentile among starters. This is over a substantially large sample size, too, which suggests that these figures are more measures of true talent than anything else. No matter how you break it down, his fastball looks good relative to the league.

That raises the obvious question: Should he throw it less? In recent years, there has been a greater emphasis on having pitchers throw their best pitches more often, which theoretically would lead to the decline of the table-setting fastball. In 2017, Eno Sarris wrote for FanGraphs that pitchers should throw 80% breaking balls. Ben Clemens, likewise, wrote in 2019 about how fastballs have become rarer than ever. Indeed, more pitchers have been opting to pitch backwards, prioritizing their best offerings over their fastball even in historically fastball-heavy counts.

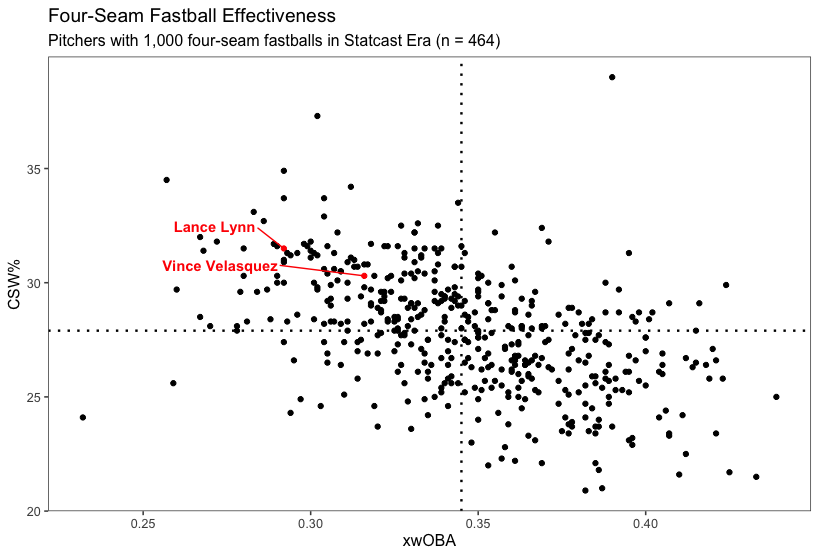

But what about for a pitcher whose best pitch is his fastball? Does Velasquez need to develop a more effective offspeed pitch (his current non-fastballs haven’t yielded great results), or should he go in the opposite direction, upping his fastball usage to the maximum? Earlier this season, Carmen Ciardiello wrote a fascinating article that helps answer these questions, as he found little evidence to suggest that throwing any pitch more or less often alters its effectiveness. If Velasquez were to become a carbon copy of Lance Lynn and throw nothing but fastballs, it might not end up making him too predictable; there’s an argument to be made that it could make him better.

Indeed, when using Statcast’s similarity tool, Lynn is one of the five most similar pitchers to Velasquez in terms of velocity and movement. The former throws a fastball more than 90% of the time, offering hitters a four-seamer, sinker, and cutter; the latter only has a four-seamer and a sinker, and he’s reduced his usage of the sinker over the last two seasons. But while there’s not much to be gleaned from a sample smaller than 100 pitches, that sinker has graded out well in terms of run value in each of the last two years and seemingly has at least some seam-shifted wake that could aid in its effectiveness if thrown more often.

Focusing back on the four-seamer: At least in terms of CSW% and xwOBA allowed, Lynn’s fastball hasn’t been worlds better than Velasquez’s:

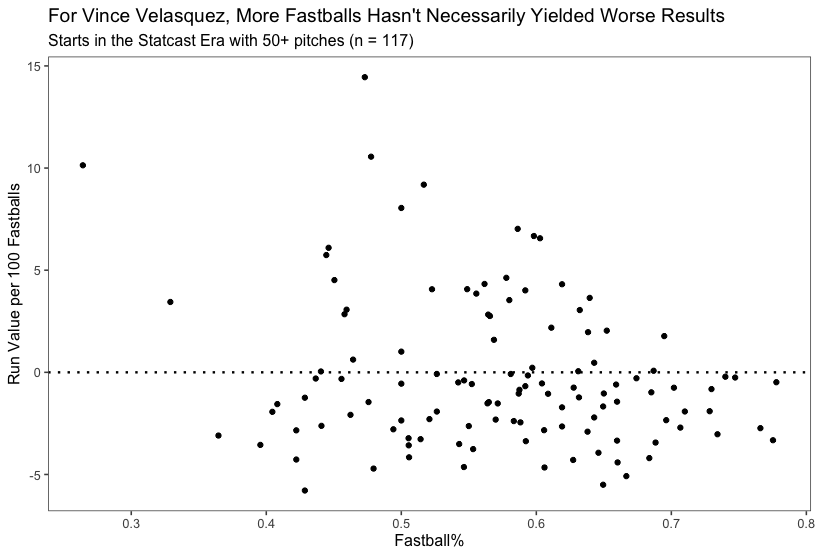

Additionally, when Velasquez has thrown the fastball more often, it hasn’t necessarily yielded worse results. There’s obvious bias that must be noted here: He may choose to throw the fastball more often on nights when he feels that he has better stuff. Even still, the pitch has graded as well above-average in starts where he’s thrown it less than 40% of the time and in starts where he’s thrown it more than 75% of the time. In this graph, zero represents average run value; above zero is better for batters, and below zero is better for pitchers:

That might not be the most effective way to demonstrate that throwing the fastball more often will absolutely work, but it goes hand in hand with Carmen’s research on effectiveness and usage. However, the individual start level may still have too much bias to comb through. A better method to evaluate Velasquez’s usage — one that spans multiple starts — is by looking at his rolling fastball usage per 100 pitches and his rolling fastball value per 100 fastballs in those segments. I did exactly that, focusing again only on pitches he’s thrown while a starter:

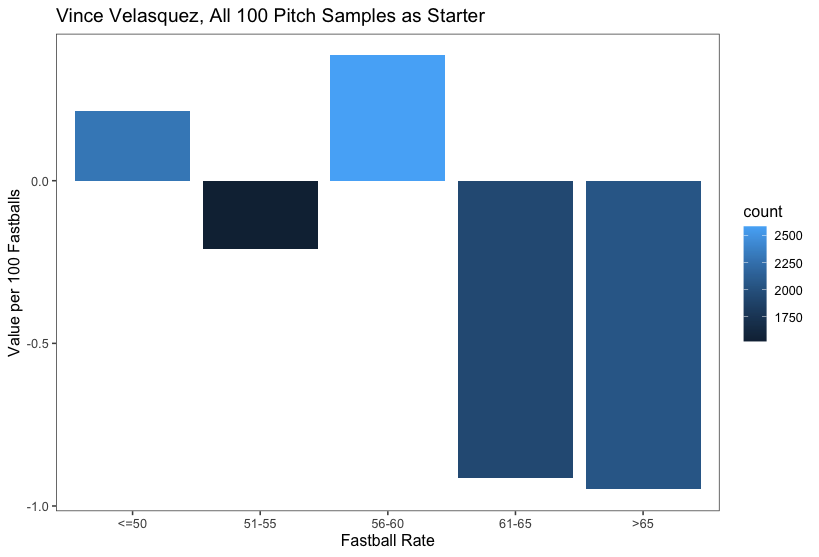

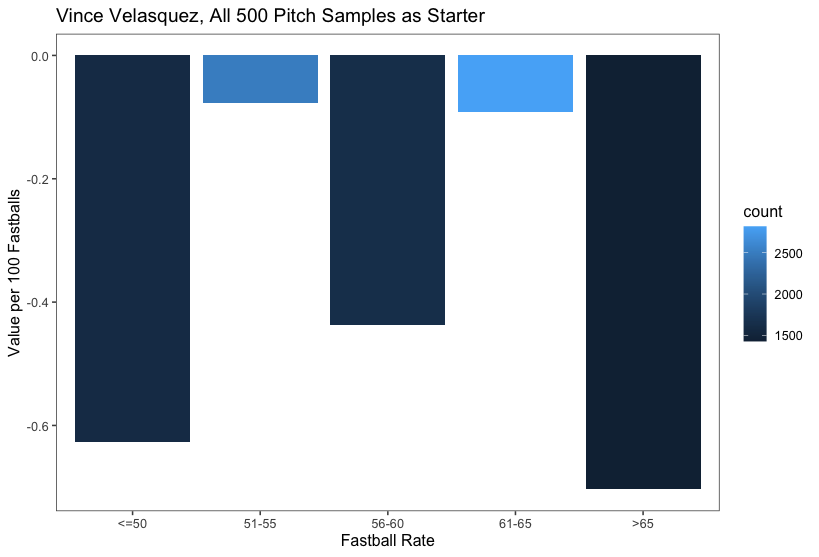

The results align closely with my theory that Velasquez should throw his fastball more often in order for it to be more effective; in 100-pitch samples where he’s done so, his fastball has seen better results. But 100-pitch samples are still quite small — in some cases not much more than a single start. If we increase this to 500-pitch samples, the relationship does change, and it becomes even more interesting:

There’s a lot here, but first, check out the color: For most 500 pitch samples of Velasquez’s career, he’s used his fastball between 51–55% of the time or between 61–65% of the time. Both of these groups have more than 2,500 samples, but what’s interesting even when you consider just those two is that the effectiveness of Velasquez’s fastball is relatively unchanged: -0.077 runs per 100 pitches in the former group, -0.091 runs in the latter. This suggests that replacing his fastball with a worse pitch when using it less often would, in theory, make him a worse pitcher.

Velasquez’s bread-and-butter is his four-seam fastball. In an era where pitchers are constantly being told to throw their best pitches more often, why should he try to adopt a different strategy? If throwing it more often won’t reduce its effectiveness — still a big if — then he would be a much more productive pitcher using it the majority of the time. Who’s to say he actually wasn’t doing exactly what he needed when he struck out all those Padres with mostly fastballs?

Devan Fink is a Contributor at FanGraphs. You can follow him on Twitter @DevanFink.

VV can’t make it a 3rd time through the order.

Career OPS against:

1st time: .768

2nd time: .760

3rd time: .926

Those 1st 2 aren’t anything great but they’re at least in the realm of average-ish. But he gets crushed the 3rd time through. Maybe upping his FB usage will change that but I doubt it.

Someone needs to finally just convert him to full-time reliever but I think he is resistant to the idea. To me, he has “failed starter who goes to the pen, throws 95-96 instead of 93-94, and dominates” written all over him. Guy turns 30 next year and could easily stick in the bigs for another 7-8 years if he just gives in and goes to the pen, maybe even longer given his athleticism.

At the moment, the Padres have very few pitchers who are making it to, much less through, the third time through the order.

At the moment, the Padres have very pitchers.

I don’t know why you can’t have him as a piggyback starter or MIRP type of guy, at least for now. That’s what you usually do with guys who under no circumstances should go to a third time through the order. Maybe long-term he’d be better as a high-leverage relievers but those results suggest he could handle a piggyback starter role.

Well, it’s not like the Padres actually have anyone better and currently healthy to fill his spot in the rotation if they did move him to the bullpen. Perhaps they could try a piggyback situation, but who’s the long reliever they would use alongside him?

Well, he didn’t even get the chance to pitch to anyone 3 times tonight, and he still sucked.

Having trouble the third time through isn’t like a unique or rare problem for SPs. Twice through has it’s Value, more innings you don’t have to cover with a dozen different pitchers part around for health mostly around to suppress workloads and salaries anyway

I think part of why he stinks as a reliever is part of his problem as a starter- that he tries to be too fine with his pitches all the time, and it leads to a lot of baserunners, and then one mistake happens and the whole game is broken open. I mean, he walked 45 guys in just 81ish innings this year with the Phils. I know that’s not insane, but that’s a pitcher putting a free guy on every other inning. Throwing mostly FBs might help that a little as he’d be forced to challenge hitters more, but I mean there’s a good reason also why he’s not challenging hitters, because when he does it ends up real bad too.