2022 Golden Days Era Committee Candidate: Billy Pierce

The following article is part of a series concerning the 2022 Golden Days Era Committee ballot, covering managers and long-retired players whose candidacies will be voted upon on December 5. For an introduction to this year’s ballot, see here, and for an introduction to JAWS, see here. Several profiles in this series are adapted from work previously published at SI.com, Baseball Prospectus, and Futility Infielder. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball-Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

Billy Pierce

| Pitcher | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Billy Pierce | 53.4 | 37.9 | 45.6 |

| Avg. HOF SP | 73.3 | 50.0 | 61.7 |

| W-L | SO | ERA | ERA+ |

| 211-169 | 1,999 | 3.27 | 119 |

An undersized southpaw listed at just 5-foot-11 and 160 pounds but armed with a blazing fastball, Billy Pierce earned All-Star honors seven times during his 18-year career (1945, ’48-64) and helped both the 1959 White Sox and ’62 Giants to pennants. He ranked among the game’s best pitchers during the 1950s, posting a higher WAR (43.9) than any other AL hurler and running second in both ERA+ (128, behind Whitey Ford‘s 140) and wins (155, behind Early Wynn’s 188) during that span. Had each league issued its own Cy Young award — which didn’t happen until 1967, 11 years after the first one — Pierce likely would have taken home some hardware.

Pierce was born in Detroit on April 2, 1927, and grew up in suburban Highland Park, Michigan. As he once said, he began playing baseball at age 10; after he refused to have his tonsils removed, his parents coerced him by offering a major league baseball and a good glove. “I took the bribe,” he said. “It really was a thrill to throw around that league ball, and I’ve been throwing ever since.”

Initially, Pierce played first base at Highland Park High School, but took over pitching duties when his team’s regular pitcher left for a team with better-looking uniforms. In 1944, at the age of 17, he pitched in the inaugural All American Boys Game, played at the Polo Grounds in New York on a team piloted by Connie Mack; Babe Ruth was in attendance. Via his six scoreless innings in an 8-0 victory, Pierce earned game MVP honors as well as the nickname “Mr. Zero.”

Pierce signed with the Tigers and began the 1945 season on their major league roster, but he didn’t debut until June 1, when he threw 3.1 scoreless innings of relief against the Red Sox. He pitched just two more times before being sent to Triple-A Buffalo, then returned in September. Though he threw just 10 innings, he received a ring when the Tigers beat the Cubs in the World Series.

Even so, Pierce shuffled off to Buffalo for two more seasons, and struggled with his control, walking more than seven batters per nine. He was similarly wobbly with the Tigers in 1948, walking 8.3 per nine while getting touched for a 6.34 ERA. Even after being traded to the White Sox for Aaron Robinson in November 1948, and posting better-than-average ERAs in both ’49 (3.88 ERA, 107 ERA+) and ’50 (3.98 ERA, 113 ERA+), he walked more batters than he struck out in those years.

Pierce’s career took a major step forward when Paul Richards took over as the manager of the White Sox before the 1951 season and had the lefty add a slider to go with his curve. “Developing a slider helped me tremendously because it gave me a third out pitch,” Pierce later said. “I threw it almost as hard as my fastball, but I could throw it for strikes better than the fastball or good curve.”

The new pitch helped Pierce cut his walk rate to 2.7 per nine, less than half of what it had been the year before, and lower his ERA to the extent that he placed in the top six in that category in 1951, ’52 and ’53, with a low of 2.57 (142 ERA+) in the middle year. In 1953, Pierce went 18-12 with a 2.72 ERA (second in the AL) and a league-high 186 strikeouts en route to the circuit’s top WAR (6.2). He also made his first All-Star team and his first of three All-Star starts, throwing three scoreless innings.

After an off season in ’54, Pierce led the AL in both ERA (1.97) and WAR (7.0) in 1955, and added another three-inning scoreless start to his All-Star resumé. He reached the 20-win plateau in 1956 and ’57, striking out a career-high 192 in the first of those seasons, good for second place. He took the loss in the 1957 All-Star Game, albeit for yielding a singe run in his three-inning start.

With a cast that included Minnie Miñoso, Hall of Fame double play combo Nellie Fox and Luis Aparicio, and later Larry Doby as well, the White Sox averaged 89 wins a year from 1953-58, though they never finished higher than second. They finally broke through in 1959, winning 94 games and the pennant, but by that point, Pierce had been surpassed by Wynn (acquired from Cleveland in a deal for Miñoso in December 1957) and Bob Shaw as the team’s best starter; his 3.62 ERA was nearly a run higher than the year before. He threw a 16-inning complete game against the Orioles on August 6, one that ended with a 1-1 tie, but it probably did more harm than good; Pierce posted a 4.50 ERA and 5.54 FIP the rest of the way, and made a three-week trip to the injured list for a hip injury amid that stretch. His late-season woes limited him to four scoreless innings of relief during the White Sox’s World Series loss to the Dodgers.

Pierce had two more slightly better-than-average seasons with the White Sox, and then on November 30, 1961, he and Don Larsen were traded to the Giants for four players, including future All-Star reliever Eddie Fisher. In his new surroundings, the 35-year-old lefty turned in a strong season (16-6, 3.49 ERA, 110 ERA+ in 23 starts and seven relief appearances) and came up particularly big in the three-game tiebreaker series against the Dodgers, who like the Giants had gone 101-61 through the first 162 games. Matched up against Sandy Koufax — who, to be fair, was still not himself after missing nine weeks due to a circulatory problem in his left index finger — Pierce blanked the Dodgers on three hits in the opener.

The Dodgers won the second game, and headed into the ninth inning of the third game with a 4-2 lead, but the Giants rallied for four runs against three pitchers, and Pierce came out of the bullpen to throw a scoreless ninth inning, locking down the pennant. During his career, which took place in its entirety before the save became an official stat in 1969, Pierce notched 33 saves, often getting used in key situations on throw days — but none bigger than this.

| Pitcher | Years | G | GS | GR | SV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allie Reynolds | 1945-1954 | 370 | 267 | 103 | 44 |

| Billy Pierce | 1945-1964 | 585 | 433 | 152 | 33 |

| Warren Spahn | 1946-1964 | 710 | 633 | 77 | 28 |

| Robin Roberts | 1948-1964 | 622 | 563 | 59 | 24 |

| Bob Lemon | 1946-1958 | 460 | 350 | 110 | 22 |

| Johnny Antonelli | 1948-1961 | 377 | 268 | 109 | 21 |

| Larry Jackson | 1955-1964 | 407 | 284 | 123 | 20 |

| Hal Newhouser | 1945-1955 | 304 | 244 | 60 | 18 |

| Jim Bunning | 1955-1964 | 345 | 290 | 55 | 14 |

| Early Wynn | 1946-1963 | 583 | 517 | 66 | 14 |

| Sal Maglie | 1945-1958 | 303 | 232 | 71 | 14 |

| Harry Brecheen | 1945-1953 | 256 | 205 | 51 | 14 |

Pierce made two starts during the 1962 World Series against the Yankees. He yielded three runs in six innings in a losing cause in Game 2, but returned to throw a three-hit complete-game victory opposite Ford in Game 6. Alas, the Giants lost Game 7, 1-0.

After the season, Pierce tied for third in that year’s Cy Young balloting behind Don Drysdale and Giants teammate Jack Sanford. This was the only season in which he received a Cy Young vote — ballots only went one deep in those days — and even though he received just one, the recognition was odd because he had a comparatively light workload (162.1 innings) and no real impact on the leaderboards, traditional or advanced, besides ranking 10th in the NL in wins and fourth in win-loss percentage (.727).

Pierce didn’t have much left in the tank after that. He pitched two more years for the Giants, relieving more often than starting, drawing his release after the 1963 season but then being re-signed and making the club the following spring. The 37-year-old lefty announced his retirement on the final day of the 1964 season.

As a Hall of Fame candidate, Pierce never got any traction on BBWAA ballots. He made five appearances from 1970-74, debuting with 1.7% and never clearing 2%. Per the research of Graham Womack, he wasn’t named as a candidate under consideration by the Veterans Committee before its 2003 expansion, and he didn’t make any of those expanded VC ballots either. In fact, his 2015 Golden Era Committee ballot appearance was his first; he landed in the dreaded “three or fewer votes” category, though like Ken Boyer and Gil Hodges, who were in that same boat, he’s back for another shot in this format.

Pierce’s case doesn’t look tremendously strong. His career was just 3,306.2 innings long, and aside from the 200-win mark, he didn’t hit any major milestones; in fact, he fell one strikeout short of 2,000. His postseason resumé is impressive but brief (1.89 ERA in 19 innings). His Hall of Fame Monitor score of 82 is well below even the 100 that marks “a good possibility.”

That said, Pierce does stand out in several ways. His strikeout rate was 27% above the league average, and his strikeout-to-walk ratio was 46% above league average (both of those measures come via our “+ stats” suite). Pierce ranked among the AL’s top 10 in strikeouts nine times (six times in the top five). He was very good at run prevention, as both his 119 ERA+ and six times on the ERA leaderboard (four of them in the top five) both attest. He made the AL WAR top 10 seven times, with two league leads and six top-five finishes. Had the Cy Young award been around during his heyday, it’s not out of the question that he could have taken home a couple, particularly during the 1952-58 stretch, his peak.

From an advanced metrics standpoint, Pierce fares much better than the Golden Era ballot’s other pitcher, Jim Kaat, who threw 37% more innings than Pierce but allowed 11% more earned runs relative to the league (via ERA+, where Pierce has a 119-108 edge) and had a strikeout rate that was 10% below the league average.

| Pitcher | IP | RA9 | RAOpp | Radef | PPFp | RA9Avg | RAA | RAR | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pierce | 3306.2 | 3.61 | 4.52 | 0.19 | 97.9 | 4.25 | 231 | 513 | 53.4 |

| Kaat | 4530.0 | 4.05 | 4.05 | 0.10 | 102.6 | 4.11 | 50 | 401 | 45.2 |

Pierce’s rate of earned and unearned runs allowed (RA9) is over four-tenths of a run lower than Kaat’s. He shut down offenses that scored an average of 4.52 runs per nine, while the offenses Kaat faced scored an average of 4.05 per nine — put a pin in that one, I’ll get back to it. Pierce had better defensive support (including Aparicio and Fox, both of whom won multiple Gold Gloves behind him), but he also worked in more pitcher-friendly parks that reduced offense by an average of just over 2%, where Kaat toiled in more hitter-friendly parks. By B-Ref’s reckoning, a league-average pitcher under the same conditions as Pierce would have yielded 4.25 runs per nine, compared to 4.11 runs per nine for Kaat. The gaps between those figures and each pitcher’s RA9 when translated into runs above average, runs above replacement, and WAR yield significant advantages for Pierce.

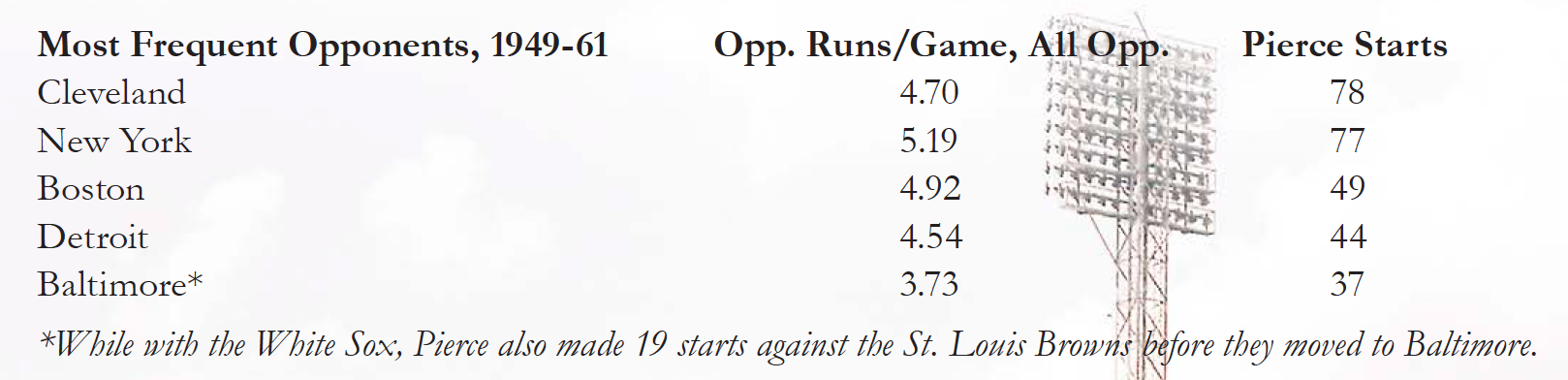

That high scoring rate for the offenses that faced Pierce wasn’t a fluke. Pierce’s managers, Richards and Al Lopez, planned his starts so that he’d face the best teams most often, even if it meant fewer total innings. According to the Billy Pierce Golden Days Era Hall of Fame Book, a slick and well-done PDF put out by the White Sox’s communications department, while with Chicago Pierce faced the Yankees and Cleveland nearly 80 times while not facing any other team more than 50 times:

The book goes on to point out that Pierce outpitched Ford in the 15 head-to-head matchups between the two, with an edge in ERA (2.49 to 2.89) and innings (119.1 to 102.2) as well as peripherals. Ford, whose career more or less coincided with Pierce’s, did not have to face the Yankees, of course, and so it turns out his RA9Opp was just 4.26. Most of that comes out in the wash; Ford had 53.5 pitching WAR in 3,170.1 innings to Pierce’s 53.4, though he did have a 57.0 to 53.4 advantage including offense. Pierce’s career WAR ranks 93rd among pitchers, in the neighborhood of Jerry Koosman, Bucky Walters, David Wells, Dwight Gooden, and Hall of Famers Burleigh Grimes and Waite Hoyt; in all, he’s ahead of just 13 of the 65 non-Negro Leagues Hall of Fame starters. His 37.9 WAR peak ranks 122nd, five spots below Kaat, just ahead of Mickey Lolich and Cole Hamels, and 44 spots ahead of Ford (34.8). Pierce is 102nd in JAWS, three spots below Ford (45.8), again ahead of 13 out of 65 enshrined starters.

As noted within my Kaat profile, behind the scenes I’m experimenting with an unpublished version of JAWS, one that will be used to supplement my candidate evaluations and that may be published in the coming weeks. A bit of explanation:

The idea is to prorate the peak-component credit for any heavy-workload season to a maximum of 225 innings in an attempt to reduce the skewing caused by the impact of 19th century and Deadball-era pitchers, some of whom topped 400 innings in a season on multiple occasions. Cy Young’s 453-inning 1892 season, which produced 11.2 pitching WAR and -0.9 hitting WAR, thus counts as about 5.2 WAR for his peak score (still 10.3 for his career WAR). Old Hoss Radbourn’s record-setting 678.2-inning 1884 season, the one in which he notched 59 or 60 wins (depending upon the source), scales from 19.2 pitching WAR and 0.3 hitting WAR to a total of 6.5 WAR for his peak score. By my calculations, doing this for all Hall of Fame pitchers drops the peak standard from 50.0 to 40.7, which lowers the JAWS standard from 61.7 to 56.9. Most notably this pushes some pitchers in the 50ish JAWS range — guys like Kevin Brown, Rick Reuschel, Wes Ferrell, Luis Tiant, and David Cone — closer to the standard but not quite over it.

This methodology actually helps Pierce relative to other pitchers of his era because he wasn’t quite the workhorse, though he did rank among the AL’s top five in innings five times. His adjusted seven-year peak WAR only drops from 37.8 to 37.0, whereas Kaat’s drops from 38.1 to 34.5. Pierce’s NL contemporary Robin Roberts, who had six straight seasons of at least 300 innings to start the 1950s, drops from a peak score of 54.9 to 43.4 by this methodology. Instead of being 15.1 points below the JAWS standard, this experimental version leaves Pierce 11.7 points below the standard.

That’s interesting, but it doesn’t change my conclusion. Given his comparatively modest postseason impact and collection of honors — particularly compared to Ford, a pitcher I think WAR and JAWS significantly underrates — Pierce doesn’t appear worthy of a vote in this context. As with Roger Maris, it feels like he’s along for the ride on this ballot, a very good player in his time but not a candidate with a convincing case for enshrinement.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

He’s a real candidate that merits consideration. 27 bWAA. You could add 1 for postseason. 69 fRA9 WAR is Hall worthy. A decent but unexceptional peak with 3 years over 6 BWAR and 3 more with 5 bWAR. Another case of vastly different BB-Ref and FG numbers. He’s a either a borderline case or easily worthy depending on what these numbers mean and what the voter values.