A Defining Moment Slips Away From Zack Greinke

It is not an indictment of a pitcher to allow a home run to Anthony Rendon. He hit 34 of those this season, and 104 over the past four seasons combined. It is also no grand failure to walk Juan Soto. The precocious 21-year-old was issued 108 free passes this season, the third-most in the National League. He also hits for quite a bit of power, so sometimes, a pitcher is content watching Soto trot down to first if it doesn’t mean he just yanked a pitch into the seats. When Rendon homered and Soto walked in back-to-back plate appearances in the seventh inning of Game 7 of the World Series on Wednesday, it wasn’t, as Craig Edwards wrote earlier today, a sure sign that Houston starter Zack Greinke had run out of gas. But it was spooky enough to make Astros manager A.J. Hinch reach for his bullpen, bringing in Will Harris to face Howie Kendrick with a 2-1 lead.

By now, you know what happened next. Kendrick poked his bat head through the bottom of the zone and got enough of a Harris fastball to drill the foul pole in right field for a two-run homer. The shot gave the Nationals their first lead of the game, and they never looked back, adding three more runs the rest of the way while their bullpen stymied Houston’s destructive lineup en route to a 6-2 final and their first World Series championship in franchise history. Harris is a very good pitcher, and he made a good pitch — a cutter that was on track to perfectly dot the low and outside corner of the strike zone. But Kendrick came up with the only possible swing that could have done damage against it, and in doing so, delivered a fatal blow to the Astros’ historically great season. It also nullified a performance by Greinke that could have served as the defining moment of his career.

Greinke allowed two runs in six and two-thirds innings on Wednesday, despite allowing just four baserunners. For comparison’s sake, his counterpart, Max Scherzer, allowed the same number of runs in five innings while allowing 11 to take base. Before the two-out homer and walk in the sixth, Greinke had been spectacular. He faced the minimum 12 batters over the first four innings of the game, allowing just one hit — a single by Soto — that was wiped out on a double play. He issued his first walk with one out in the fifth inning against Kendrick, but bounced back from that with two quick outs to end the threat, before throwing another 1-2-3 frame in the next inning. After six scoreless, Greinke had thrown just 66 pitches. While Scherzer labored on the other side, having to gut through each inning after falling behind hitters repeatedly and setting up potentially disastrous situations with men on base, Greinke seemed to be on cruise control.

He pieced together that start with exactly the kind of craftiness one would expect from the right-hander in 2019. The 36-year-old didn’t rely on getting whiffs on Wednesday, finishing with just seven total swings and misses and three strikeouts. Instead, he used his deep pitch mix and near-flawless command to flummox Nationals hitters into producing weak contact throughout the evening. His pitch chart from Baseball Savant for the game shows few mistakes, and the breaking ball chart reveals even fewer:

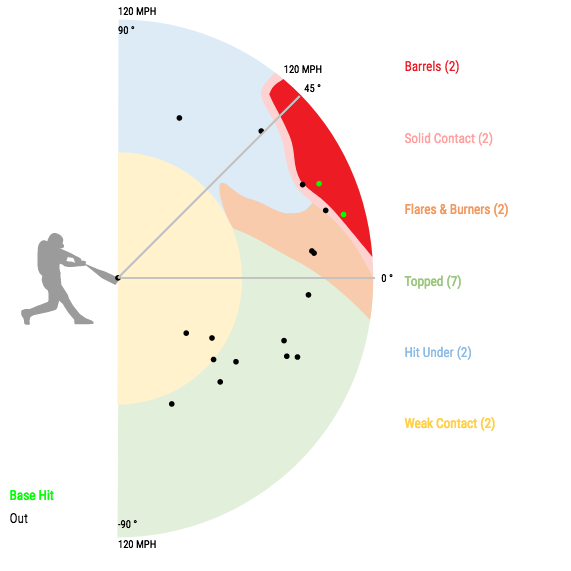

Greinke finished with 80 pitches thrown, and very few of them caught the middle of the plate. And while he used his fastball — which topped out at 91.8 mph — as somewhat of a go-to pitch, offering it 45% of the time, he split his breaking pitches up almost evenly, throwing 15 changeups, 14 curveballs, and 14 sliders (along with one eephus). Washington hitters responded by catching the top of the baseball all night.

It was fitting that this is the way Greinke would dominate in this setting. Once able to average over 94 mph with his fastball and the former major-league leader in K/9 back in 2011, it’s well-documented that he is a different pitcher these days. His average fastball velocity dipped below 90 mph for a second straight season this year, and 37 of the 61 pitchers who qualified for the ERA title this year posted a better K/9 than his 8.07. And yet, he posted his best ERA (2.93) and FIP (3.22) since 2015, and his highest WAR total (5.4) since 2009. Armed with a broad array of off-speed and breaking pitches — some of which feel like they’ll never reach home plate — he was one of the very best pitchers in baseball, and in Game 7 of the World Series, the whole world got to see why.

The fact that he was able to show off his incredible non-pitching baseball talents turned this into an even more definitive Greinke performance. No, we didn’t get to see him hit — he had a 123 wRC+ in 56 PAs this season — but we did get to see just how good he still is at defending his position in the field. With a runner at first in the top of the second, Kendrick awkwardly half-swung at a fastball up and in, and Greinke effortlessly moved off the mound to play the ball on a hop and throw to second base to start a double play. That was the first of five groundouts Greinke fielded himself, making one impressive snag after another to make his presence in the game loom even larger.

There was something deeply special about watching Greinke do this in Game 7 of the World Series. Last night, as I watched his curveballs dance toward home plate, watched his fastballs find the very bottom of the zone, watched the Nationals look mostly helpless as they beat one pitch after another into the grass in front of the mound, it occurred to me that I’d never seen Greinke get to have a moment like this, which seems sort of hard to believe. He’s pitched for 16 years, been on six different teams, and won a Cy Young Award. I think he’s a Hall of Famer, and I’m far from alone.

And yet, he’d never gotten to pitch in the World Series before this season. He’s never thrown a no-hitter. He’s never really gotten to have a singular moment, the one everyone thinks about when they see his name on the Hall of Fame ballot. Justin Verlander has his three no-hitters and a sparkling postseason track record outside the World Series. CC Sabathia threw the Yankees on his back and guided them to a title in 2009. Cole Hamels and Jon Lester both have their own defining postseason runs, while Max Scherzer has a seemingly endless list of memorable games, from two no-hitters in the same season to striking out 20 batters in a single game in 2016.

Greinke’s career, meanwhile, has been defined by other things. There was his often rocky time with the Royals, when he became great while pitching for one of the most consistently awful teams of the decade. The best season of his career came in 2009, when he earned 8.7 WAR with a 2.16 ERA and 2.33 FIP; Kansas City won 65 games. There were his three years with the Dodgers, where his consistent brilliance now contributed to a regular contender, but where he was now overshadowed by Clayton Kershaw, who made Greinke the second-best pitcher on his own team even when he pitched an entire season with a 1.66 ERA. And there is the social anxiety and depression that has seemed to follow him throughout, and that in the early years of his Royals career, threatened to end it altogether.

For six innings on Wednesday, it felt as if Greinke’s career would be defined by something else, too — a dominant start in Game 7 of the World Series that cemented a championship for one of the greatest teams baseball has ever seen, a team that traded for Greinke in July for this exact kind of moment. But then he was taken out of the game, and two pitches later, the night belonged to Kendrick. It belonged to Scherzer, and Soto, and this scrappy Nationals team that faced elimination five times this postseason against deadly relievers and overpowering super-teams and won every damn time. It was good to see the Nationals have that moment, but I was sad that cost Greinke his.

Maybe it’s selfish of me to want Greinke to have the spotlight. He’s made it clear he doesn’t enjoy being the center of attention, going so far as to say that even throwing a no-hitter wouldn’t seem worth the “hassle” it would bring upon him. I know the feeling of intense discomfort that being the focus of others can bring, even if it’s positive attention. I’ve written things I hoped were good, had someone tell me they were, and immediately felt something distressingly and perplexingly close to shame. Greinke doesn’t seem to want some big moment in which he is the centerpiece of a championship-clinching celebration, and it would be wrong of me to wish that upon him.

Back in March 2007, Sports Illustrated published a profile of Greinke. He was coming off a season in which his battles with mental illness limited him to making just three appearances, totaling 6.1 innings. The season before, he had a 5.80 ERA and lost 17 games. The profile talks about him trying to fight his way back into the rotation, how he started taking medication for his anxiety and depression, how he just wanted to help the Royals win games, even if it meant changing his role on the team. Near the end of the story is this paragraph:

As good as Greinke might be, it is clear that, at least for now, his days as an ace are over. He prefers the anonymity of the bottom of the rotation to the pressures of being the stud of the staff. In fact, Greinke — soft-spoken, somewhat withdrawn but polite and accommodating in a talk after the game — said he might like to pitch out of the bullpen, an idea that he had a couple of years ago when he hated the game and believed pitching more often might make him hate it less.

At first glance, the passage couldn’t seem more wrong. Greinke obviously became one of the best pitchers of his generation, and has been an ace for several different teams. He hasn’t pitched out of the bullpen since that 2007 season, and hasn’t been regarded as a back-of-the-rotation arm since. In some ways, though, it still fits. Greinke wasn’t the “stud of the staff” as a member of the Dodgers, and pitched the second half of this season in a rotation with two Cy Young candidates ahead of him. There aren’t many teams in baseball on which someone with Greinke’s production is the third-best pitcher on the staff, but he managed to land with one anyway. In Arizona, he was the star of the show; on the Astros, on the Astros, an important but supporting character.

And yet, the spotlight found him anyway. And as much pressure as there was on him as he stood on the mound in a do-or-die game in front of a home crowd that expected nothing less than a championship when this postseason started, I hope he enjoyed it. I hope the feeling of releasing the ball and having it chopped weakly back into his glove made him feel 10 feet tall. I hope that he allowed himself to feel like it was where he belonged, that all of these people should be watching him, because he was pitching his ass off in Game 7 of the World Series, and he was doing it with every ounce of poise and intelligence and grace that he’s built up over 16 years playing a game he was sure he hated. I hope he felt, even for a second, like this was his moment. I hope he gets another.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

Got some of that dust in my eye reading the last paragraph.

read it chopping onions