A Friendly Suggestion for Stephen Strasburg, Who Is Already Very Good

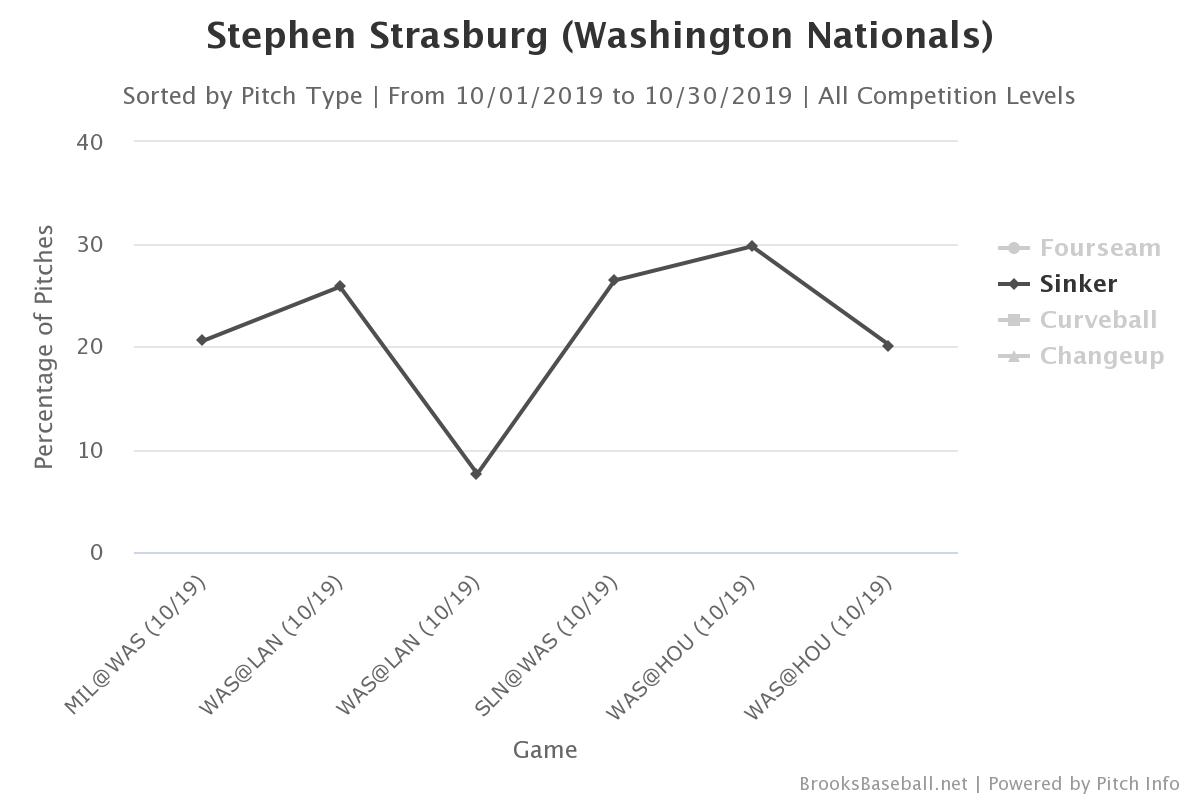

Stephen Strasburg has apparently decided to defy the notion that two-seamers are out of style in today’s game. Having rarely thrown the pitch from 2015-16, and not at all in 2017, Strasburg bumped up his use of the two-seamer in 2018, and more than doubled it in 2019. This season, pitchers threw the two-seam fastball 14.7% of the time on average; three of Strasburg’s six appearances in October doubled that mark.

That’s a sign he has a lot of faith in the pitch, considering the league wOBA for both the regular and postseason sits at .360.

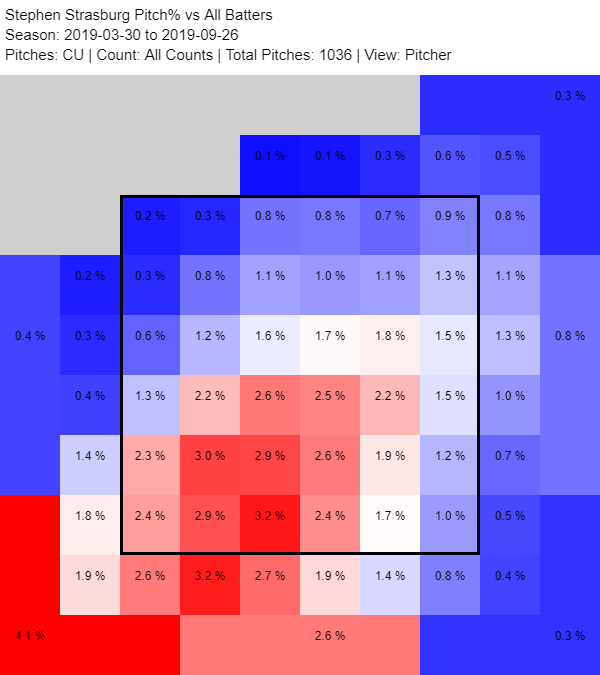

Strasburg also is using a curveball, with great success, to the tune of a .159 wOBA against. What do these two pitches have in common? Allow me to explain.

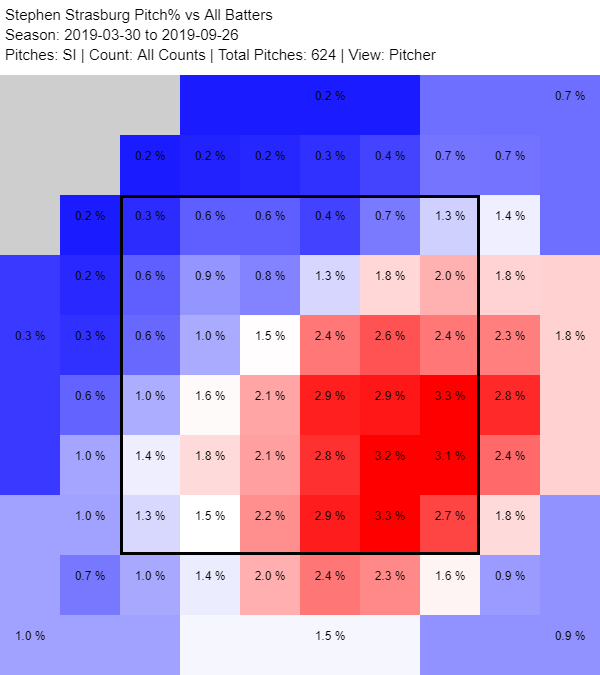

Strasburg has been keeping the two-seamer and curveball low at opposite ends of the strike zone:

Is there anything wrong with this approach? Well, yes and no. Strasburg has been arguably the most dominant pitcher this October, so he has to be doing something right. His two-seam wOBA is .352, which is high, but is right around league average. On the other hand, his curveball wOBA (.159) is much lower than the league average of .280.

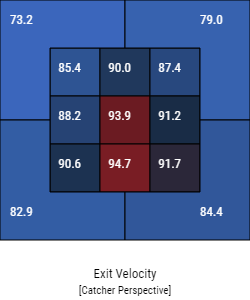

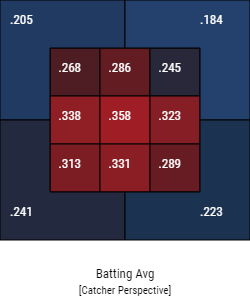

That makes for a pretty decent combo, but it could be even better. Take a look at both the league-wide average exit velocity and batting average, based on location, for the two-seam fastball across the regular and postseason. You can see hitters have been more effective hitting the pitch low in the zone.

Strasburg’s two-seam numbers are generally in line with these charts, so it stands to reason he’d be more effective keeping the pitch up in the zone. Why might he want to do that?

In a piece for The Athletic, Joe Schwarz discussed the concept of two pitches playing off of each other based on spin axis, a concept he called “pitch mirroring.” As Schwarz described it:

(In the simplest of terms, think of “mirroring” as a pitch with backspin tilted down and to the left sequenced after a pitch, with top spin tilted up and to the right). In theory, pitches with perfectly mirrored spin axes, if starting on or at least near the same path, should trace their way up to the hitter’s decision-making point only to diverge and ultimately land in very different quadrants of the hitting zone.

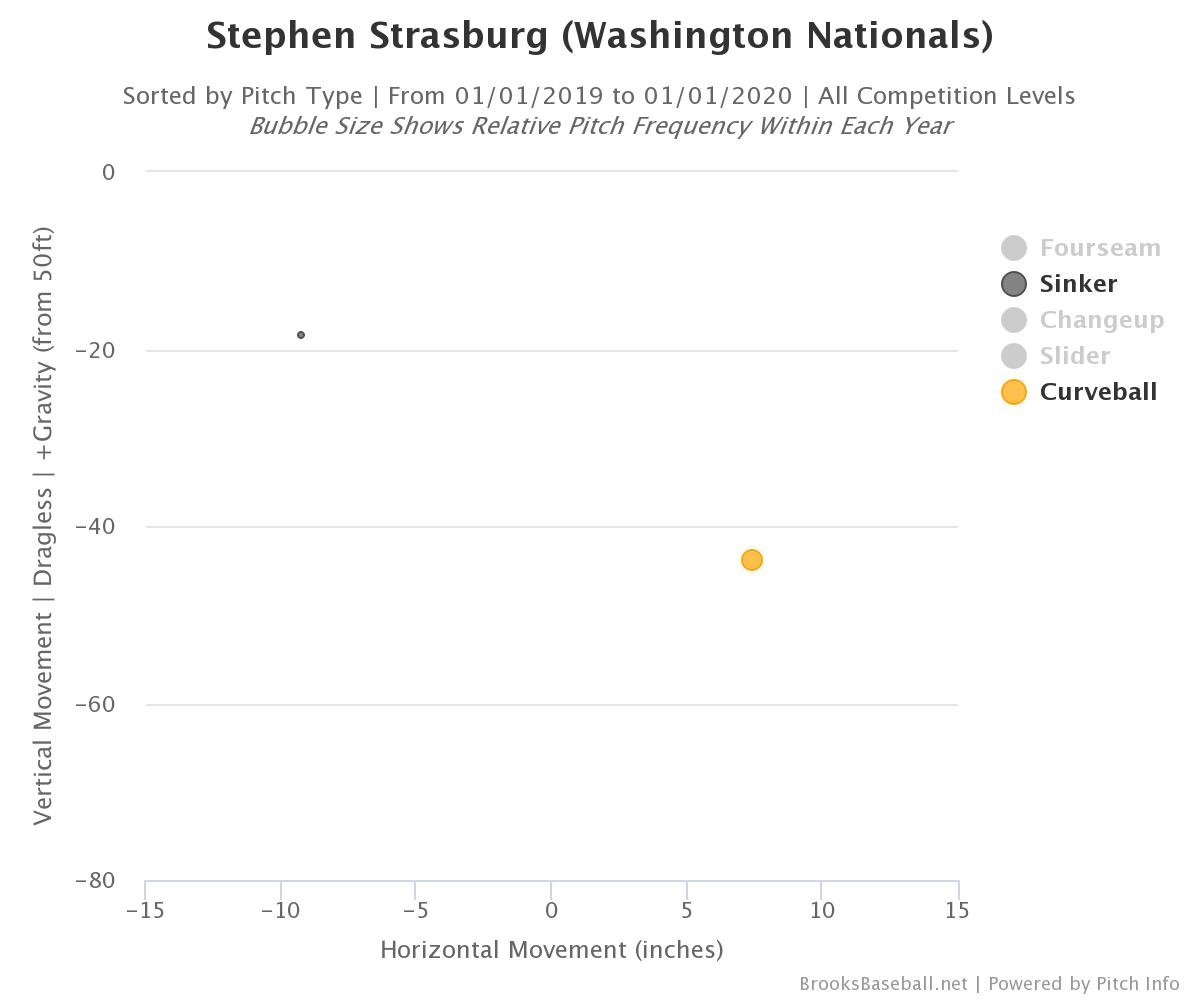

This typically works best with repelling axes around 180, 45, or 90-degrees. Strasburg’s spin axis on the two-seam is 237-degrees, while his curveball sits at around 57-degrees. That spread equals out to 180-degrees, which is ideal. The chart below shows how these two pitches can work off each other.

Think of it like a safety in football, positioned behind the rest of the defense. He’s responsible for covering two receivers lined up next to each other. If both break in similar directions, he can potentially account for both receivers. However, if they break in opposite directions soon after they cross the line of scrimmage, the safety has to decide where he thinks the quarterback will go with the ball. It’s incredibly difficult to split the difference, so the safety, who is basically guessing, likely has to commit to one or the other.

In baseball, a hitter would see back-to-back pitches coming from a similar release point (the WRs). First, he may get the fastball, then have the second pitch in the sequence coming at him from the same tunnel. Most of the time, if a pitcher doesn’t have a large movement spread between the two, it’s a bit easier for the hitter to make contact. But when a pitcher has two pitches break off from each other, in the manner Strasburg’s two-seamer and curve have the potential to do, it makes the hitter’s job much harder.

This works most effectively if you can tunnel the combo. Strasburg’s tunneling metrics on his two-seam and curve appear much better for left-handed hitters than for right-handed hitters, as the commit point spread is a bit tighter and the ratio between that and the actual location where the they cross the plate is almost twice as large. (You can find more on the hitter’s perspective on tunneling in this piece I wrote for the community blog here, as well as in Jeff Long, Harry Pavlidis, and Martin Alonso’s research for Baseball Prospectus.)

Observe, in this extreme case, how Strasburg’s pitches create this mirroring effect.

During the playoffs, Strasburg has kept both his two-seam and curve down in the zone much the same way he has during the regular season. That being the case, it would be pretty difficult to accomplish this attack without elevating the two-seamer, thereby allowing the two pitches to play off of each other on a much larger (and imposing) scale. Have a look at this overlay that demonstrates how he’s been using his two-seam and curve. You’ll see there is no tunnel; the pitch pops out of the combined trajectories soon after the release point.

With the kind of success Strasburg has had both during the regular season and in the playoffs, an change in approach isn’t required, and Strasburg’s World Series work is done anyhow. But elevating his two-seamer so that it can be more successfully mirrored off his curveball might make Strasburg an even more effective pitcher in 2020. Now that’s a scary thought.

Pitching strategist. Driveline Baseball pitch design-certified. Systems Administrator for a high school by day, I also provide ESPN with pitching visuals and am the site manager for SB Nation's Bucs Dugout.

When going curveball down and fastball up I don’t understand why the fastball would not be four seam.

For the arm side run, I think.

Because this is more about the spin axis and the contrasting spin direction. The four-seam does not have that.