Adam Frazier Has Been Interesting So Far

Adam Frazier is a Pittsburgh Pirate. He’s also been good, which means contending teams will look to acquire him at the trade deadline. What organization wouldn’t want an above-average defender who’s also hitting .330/.397/.463? To give that another spin, his 137 wRC+ is third-best among second basemen with 300 or more plate appearances, right behind Max Muncy and Jose Altuve.

But you might have visited his FanGraphs page, scrolled to the numbers, and seen a red flag – that Frazier’s .366 BABIP is abnormal, considering his career before this season. That’s not all: There are significant differences between his actual stats and Baseball Savant’s expected stats, such as slugging percentage and batting average. He’s hit just four barrels so far, none of them surpassing the 110 mph mark.

So yes, it does seem like Frazier is biting off more than he can chew. But I think we can do better than the boy who cried regression because, well, what if he’s doing something new that’s contributing to his higher BABIP? The second baseman has always been one to make consistent contact while minimizing whiffs, so it’s plausible he’s unlocked a new gear. Back in May, I broke down Freddie Freeman’s uncharacteristically low BABIP by batted ball type, so let’s do the same for Frazier. Where is he getting his money’s worth? And compared to the league average, where is he falling behind?

| Batted Ball Type | Frazier BABIP | League BABIP | Diff. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groundball | .304 | .231 | .073 |

| Line Drive | .637 | .678 | -.041 |

| Fly Ball | .173 | .113 | .060 |

These numbers are from our Splits Leaderboards, and they tell an intriguing story. Frazier is worse than average when it comes to line drives, which might be because of his middling power – a weak liner is usually an automatic out. Despite this, he’s making up for lost production via grounders and… fly balls? That’s odd. Somehow, Frazier’s fly balls aren’t leaving the ballpark or being caught by outfielders. Instead, they’re landing for hits.

Even weirder – and this is the one thing he’s been good at – is how he’s picked up those extra points of BABIP. Although Frazier has hit a couple of doubles off the wall, they don’t account for the majority of his fly balls. Besides, how conventional. This right here is more of Frazier’s forte, a blooper that finds a sweet spot in front one outfielder:

Or one that gracefully lands between three outfielders:

And so on. There are many more. Is this additional evidence that confirms Frazier’s first-half luck? Probably. But we’d be remiss to assume this is precisely why his expected stats are lower. If anything, a metric like xwOBA, which incorporates information from prior seasons to estimate the success of a batted ball, appreciates this bloop-fest.

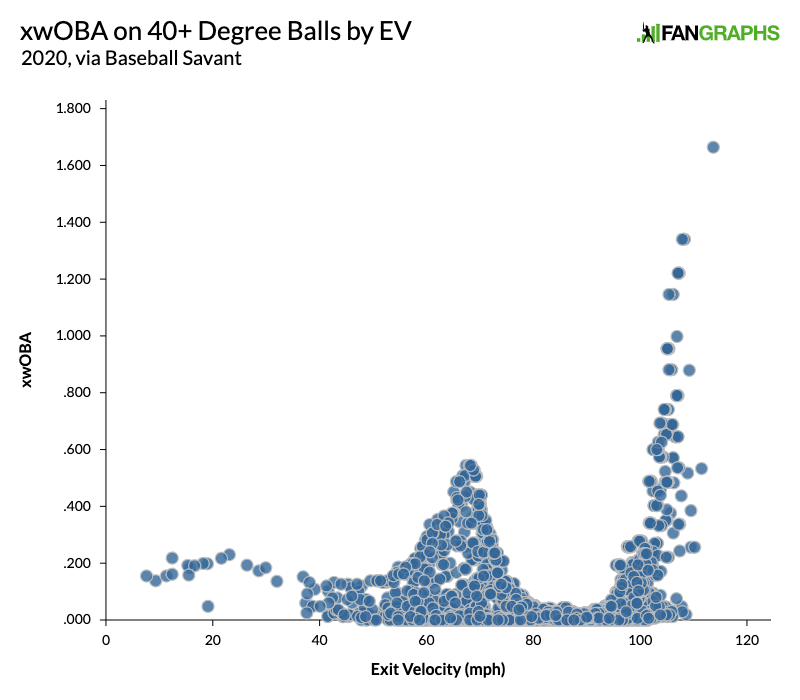

To elaborate, imagine a ball hit at an angle of 40 degrees or more. How can a hitter maximize his production on it? First, there’s the clear option of hitting the ball hard, though he would have to surpass the conventional 95 mph hard-hit threshold, and after a certain launch angle, exit velocity makes no difference. The second option is more obscure, but also works: Hit the ball at just the right combination of exit velocity and launch angle. We can visualize this, too. Here’s every single 40-plus degree ball from 2020, plotted by exit velocity and xwOBA:

As expected, at the tail end are Mike Zunino-esque moonshots that nobody would doubt. But then we arrive at the middle bunch of points that have formed a hill of their own. These are the balls expected to have a moderate amount of success, because they historically have – not too hard, not too weak, and with enough loft. In this case, an exit velocity of 80 mph is more detrimental than an exit velocity of 70 mph, which is downright silly (and awesome).

This was, in fact, my starting point before arriving at Adam Frazier. I began to wonder who had the most fly balls in the second, ideal range, and my search yielded the following results:

| Player | No. of Balls | BABIP |

|---|---|---|

| Nolan Arenado | 17 | .000 |

| Adam Frazier | 17 | .412 |

| Kevin Newman | 16 | .000 |

| Jonathan Schoop | 16 | .125 |

| Jurickson Profar | 15 | .200 |

There’s Frazier on top, close to a teammate, and with by far the highest BABIP of the bunch. He’s been the absolute best at this one specific thing. But that Arenado has no hits while Frazier has seven shows how fickle these types of batted balls are – the plot from earlier features numerous points with near-zero xwOBA – and that expected stats are descriptive rather than predictive. Arenado’s lack of success doesn’t mean his future bloopers are more likely to land for hits. In a similar vein, we can’t say that Frazier’s abundance of success will correct itself. It’s entirely possible his fortune lasts an entire season!

That leaves us with Frazier’s groundballs, which have also maintained a higher-than-usual BABIP. The good news is that at a glance, spray charts suggest he’s making an effort to go the other way, at least more often than before. Though this could have been a happy accident, here’s Frazier making life difficult for the Braves’ infield:

A batted ball like that is a great way to outperform one’s expected stats. Opposing teams seem to have caught on; they applied the shift in 30.6% of Frazier’s plate appearances last season, a rate that’s dwindled to 17.8% this season. But it doesn’t seem to have made much of a difference – there’s a negligible difference between his wOBA against shifts (.360) and against non-shifts (.378). Frazier has also increased his rate of contact, whether that be against pitches inside or outside the zone. He’s setting himself up for success better than in previous seasons.

But if there’s a reason to be pessimistic, it’s because Frazier’s groundballs have benefited from yet another factor. Here’s an example of what I mean:

Attempting to throw out Frazier is utility man Jace Peterson, whose throw is ultimately a little too slow. It’s not a routine play, sure, but I can’t shake the feeling that the outcome would have been different with Kolten Wong involved. Perhaps this is a clearer depiction:

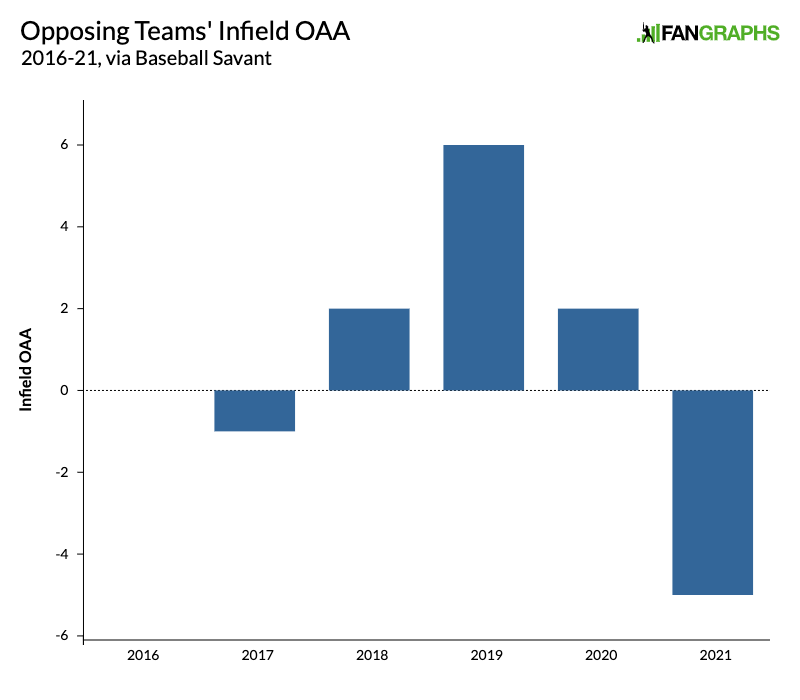

Now, this is on the first baseman – nine times out of 10, he scoops up the ball and flips it to the pitcher covering the bag. Frazier was awarded a hit since technically no error was committed, but no discerning baseball fan would ever believe he deserves all the credit. As you might have guessed, the two clips tie into a bigger trend. Consider the quality of infield defense Frazier has faced in each season of his career:

Per Outs Above Average, a cumulative metric no less, the infield he’s currently hitting into is by far the worst. Assuming that a -5 OAA represents at least a couple of hits that should’ve been outs, it’s safe to assume bad defense has left a notable mark on Frazier’s overall output. There’s undoubtedly some noise baked into a number built on a half-season sample, but it makes one wonder – would a change in scenery negatively impact the second baseman? A different team could mean a different division, which also means a different crop of infielders Frazier will face on a daily basis. It’s a question that matters.

Reading through what I’ve written, I realize there’s no central thesis, which I guess happens when meandering through a lot of tables and observations about an individual (oops). But also, I can’t in good faith claim with certainty whether Frazier will regress towards his career norm or not. Intuitively, he looks like a prime candidate, and there’s a chance none of this matters in the following months.

That being said, he’s a more interesting player than you might think. Thanks to his excellent bat-to-ball skills, Frazier is a pro at sending fly balls to the outfield rather than foul territory, where they become more vulnerable. He uses the entire field, not just the pull side. And in two-strike situations, he’ll defend himself by making contact and putting balls into play; the GIF from earlier against the Braves is an example. Frazier isn’t a 137 wRC+ hitter, of course, but he doesn’t seem like a below-average one, either. It’s up to contending teams to weigh the risks against the rewards, and how they could make the most of an offensive profile like this.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

Just for fun, I looked up infield OAA by team. Here are the worst teams in MLB:

Angels -20 (they lost Simmsons, Rendon has been hurt, this checks out)

Tigers -18 (revolving door at every infield position)

Reds -17 (three third basemen, so this checks out)

Brewers -17 (kind of a surprise but they have been slammed at third base)

Phillies -15 (Ben Clemens wrote an article on them, I think)

Red Sox -14 (Xander Bogaerts at short, Devers at third)

Braves, Dodgers, Orioles, and Blue Jays are next. Overall if you hit the ball on the ground a lot you are definitely best off in the NL Central and worst off in the NL West. The AL West is bad for you too, unless you’re playing the Angels in which case you’re good.

Frazier doesn’t actually hit the ball on the ground that much though–I think he’s pretty close to league average, and he’s actually done better in that department than most of the other Pirates. If we’re going to take this seriously, I would think that this would have an even bigger impact on Ke’Bryan Hayes, Phillip Evans, and Colin Moran. And they’re all outperforming their wOBA too, but not that much–like around .015. Adam Frazier is about twice that, which makes me think that the first issue is the real story.