The Good and Bad News About Freddie Freeman

On Wednesday, Ben Clemens investigated Francisco Lindor’s struggles as a New York Met. The answer was complicated, as in most cases, though he did treat us to a series of tables and graphs. Inspired by the endeavor, I wanted to take a crack at a different NL East superstar: Braves’ first baseman Freddie Freeman.

To be fair, his predicament is hardly as lamentable as Lindor’s. As of writing, Freddie Freeman has a 115 wRC+. There have been stretches where he put up similar levels of production. Nothing seems out of the ordinary – just a good hitter in a dry spell. It’s not like he was going to replicate his abbreviated MVP campaign, anyways.

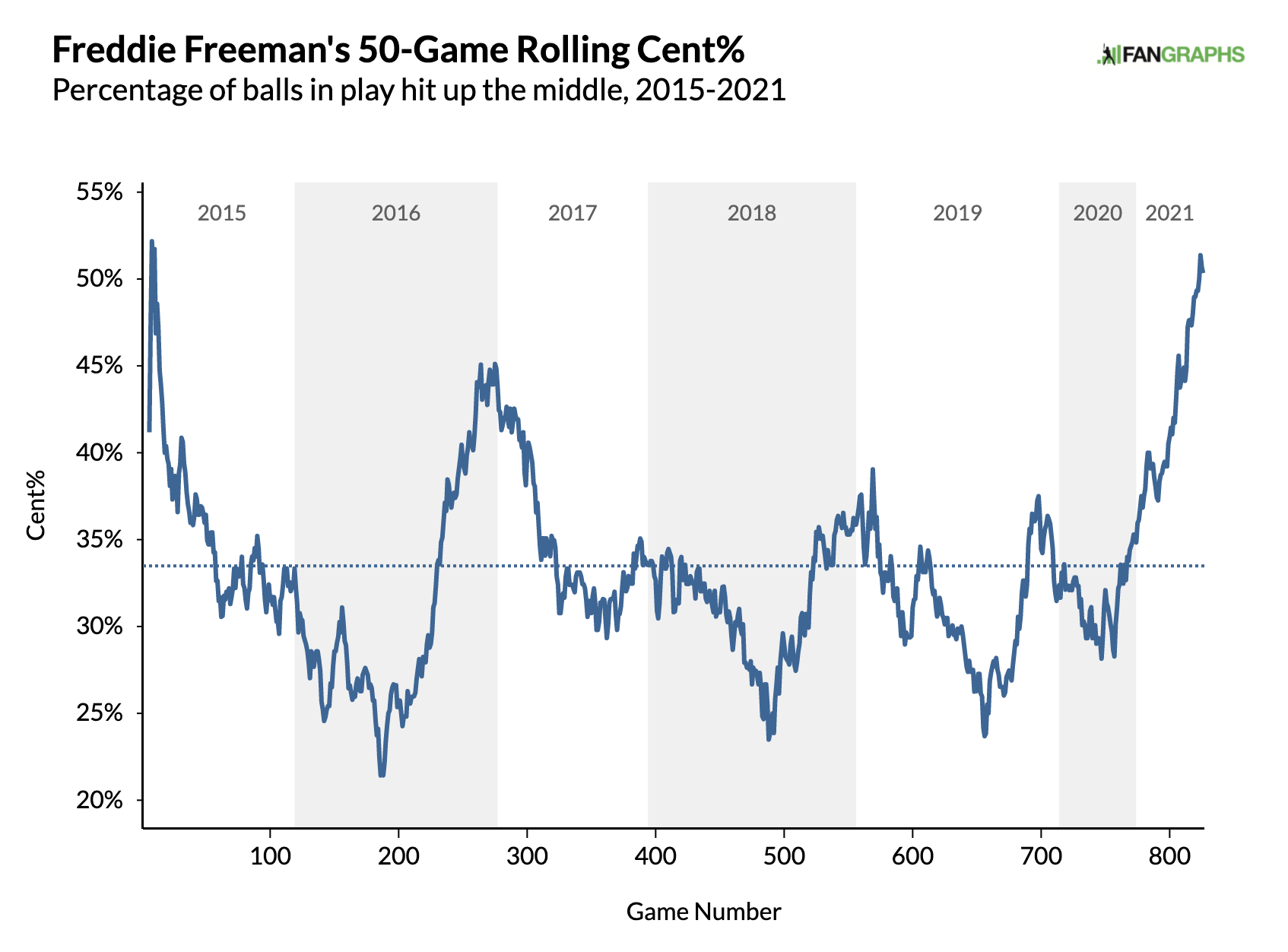

What is uncharacteristic, however, is his .224 BABIP. It surprised me, considering that he’d sustained a BABIP of .341 from 2010-20, a feat that required a decade of hard-hit line drives and an above-average contact rate. Gary Sánchez, he usually is not. But it’s been an odd year for the first baseman so far, which we can see for ourselves. Below is his 50-game rolling BABIP, stretching back to a few years ago:

At first, the explanation for this seems simple. Freeman currently carries a line drive rate of 24.5%, his lowest since 2011. His groundball rate, in contrast, is the highest since then. Fewer line drives and more grounders is a terrible combo for a hitter’s BABIP – the former land for a hit over half the time; the latter are snagged by infielders. But this raises a question. If Freeman’s current batted ball distribution resembles his in 2011, how did he achieve a .339 BABIP that year?

With that in mind, let’s switch gears for a minute. We can look at Freeman’s BABIP this season by batted ball type to narrow in on the source of his troubles. In addition, including data from previous seasons gives us a better picture of where he’s at relative to his career. Here’s all that, Statcast era onwards:

| Year | Line Drive | Groundball | Fly Ball |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | .592 | .223 | .130 |

| 2016 | .734 | .244 | .067 |

| 2017 | .589 | .262 | .205 |

| 2018 | .659 | .192 | .188 |

| 2019 | .604 | .206 | .141 |

| 2020 | .615 | .224 | .233 |

| 2021 | .590 | .097 | .056 |

Good news! The takeaway is that Freeman’s low BABIP seems more like a fluke than the result of a serious problem. I’d have been concerned if the drop came from line drives, but he’s been as consistent as ever. Instead, Freeman is losing hits from grounders and fly balls, which are subject to greater variance. Whether or not a grounder ends up a hit can depend on factors outside the batter’s control, such as the infield defense. As for fly balls, maybe the deadened ball has stolen would-be doubles off the wall. But again, Freeman isn’t responsible for that. And by definition, BABIP ignores that all 12 of his home runs this season were fly balls.

Is Freeman off the hook? Not so fast. This season is not just uncharted territory in terms of BABIP, but also batted ball direction. Freeman is sending balls up the middle at a rate that hasn’t been seen since the start of 2015:

The upward trend has significant implications for his offensive output. An abundance of line drives is a big part of it, sure, but so is a knack for pulling the ball. Freeman’s pull rate in 2021 is the lowest of his career, while his up-the-middle rate is the highest of his career and by a whole lot – it sits at 50.7%, to be exact.

Suddenly, what was once natural to him has disappeared. And it matters because pulled line drives outperform their non-pulled counterparts. Using last season as an example, when batters hit a pulled line drive, they mustered an .862 wOBA. On straightaway and opposite line drives, that figure plummets:

| BB Direction | wOBA | xwOBA | wOBA – xwOBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pull | .862 | .793 | .069 |

| Straightaway | .646 | .732 | -.086 |

| Opposite | .654 | .633 | .021 |

Expected stats don’t take batted ball direction into account, however, so they mask that truth. Consider the gap in xwOBA between pulled (.793) and straightaway liners (.739), which is smaller than the gap in regular wOBA. The discrepancy is caused by hitters generating higher exit velocities on pulled balls, but nothing else. Over on Baseball Savant, Freddie Freeman’s page is awash in a sea of red. Although I do think he has been a victim of some batted ball luck, it’s clear that his production is being overestimated to some extent. The bottom line: Freeman hasn’t been his usual, pull-happy self, and it’s limiting what he can accomplish.

More importantly, though, why is Freeman struggling to pull the ball? Two ideas come to mind. First, maybe this isn’t an accident. Maybe he’s become cognizant of how often teams are shifting against him, so all those up-the-middle balls are an attempt to beat them. It’s worked so far, at least. Freeman’s wOBA against the shift is 43 points higher than his wOBA with no shift in place, though the small sample warning is applicable here.

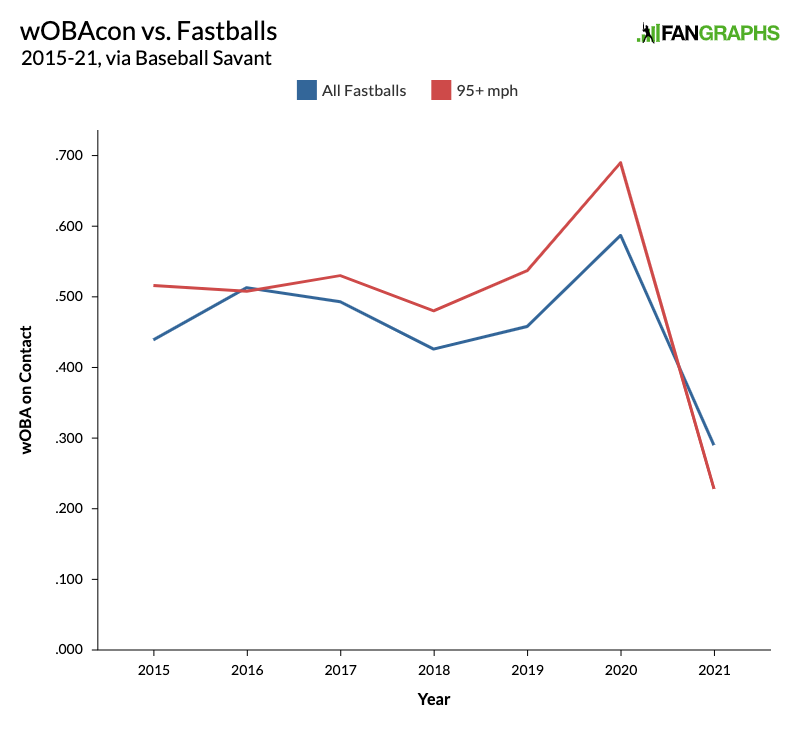

Second, Freeman’s bat speed might have declined. This is a strong claim to make, so I’ll be careful. Yes, I don’t have access to bat speed data, and yes, I’m unaware of his physical condition. But something caught my eye recently, and it seems relevant to the discussion. Now, Freeman has always demolished fastballs. Not just four-seamers, mind you, but the whole package. In 2020, he posted a .587 wOBA against them on contact. That’s great, but what if we add in a velocity requirement, say, at least 95 mph? Sure, that’ll be a .690 wOBA. What about his other, non-MVP seasons? Freeman’s wOBAcon on all fastballs was .537 the year prior. You get the point. But then we consider 2021, and well:

It’s baffling, especially the precipitous drop versus high velocity. Freeman does have a higher xwOBA, but it’s still far lower compared to previous seasons. The culprit could be age. It could also be a mechanical issue. He’s been healthy all season, so it’s likely not related to injuries. If it’s true that his bat speed is down, though, his problems make a whole lot more sense. Without a fast bat, it’s harder to yank pitches. The bat seemingly drags through the zone instead, sending the ball the other way or towards second base.

In April of 2016, SB Nation’s MLB Daily Dish published an article about Freddie Freeman’s cold start. Up to that point, he’d been hitting .203/.329/.275 with a low BABIP. Here’s a revealing excerpt:

“According to a report from David O’Brien of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Freeman had begun working on some minor adjustments with Braves’ hitting coach Kevin Seitzer back on Friday. Freeman specifically cited that his ‘bat speed is just not there.’”

Of course, he ended that season with a .302/.400/.569 line. It’s important that Freeman had bat speed issues before and managed to overcome them, which bodes well for his future this season. Together with the BABIP data, they constitute the good news about Freddie Freeman. His line drives have continued to land for hits at the same rate as before, and there’s little he can do about his other batted balls. They’ll turn in his favor at some point, though we can’t say when. His plate discipline has been stellar – he’s walking just as often as he’s striking out – which provides him a safe floor, no matter how wildly his contact quality fluctuates. The home runs are still there, contributing to a .216 ISO.

The bad news, though, is that his actual problems lie elsewhere. Freeman’s output has long been buoyed by pulling the ball, but so far, that skill has been absent on many occasions. Among the myriad of potential reasons behind it, his atypical struggles to damage fastballs stand out. Pitchers have noticed, too, and are taking advantage. Last season, they offered Freeman a fastball 52% of the time, a rate that’s climbed to 58.5% this season. Maybe this is a temporary lapse. But it could also signify a decline in bat speed, a problem that could worsen further down his career if not resolved soon.

The new baseball is having an influence, no doubt. Freddie Freeman appeared in Dan Syzmborski’s article regarding BABIP outliers, in which he surmised that “we’re seeing the effects of the slightly deadened ball.” But this is a report on what I could put in terms of concrete numbers. A 115 wRC+ isn’t bad, but for Freeman to return to his status as a perennial MVP candidate, he needs to re-discover the approach that made him successful. This isn’t the first time he’s faced adversity, so I assume he’ll figure it out. It’s merely taking longer than usual – and that’s okay.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

Good article and one can only hope that if it is bat speed, FF can make an adjustment like he did in 2016. Also, how good is FF that when he is “struggling” he is still 15% better than the league avg, just amazing.

It’s like Yelich’s self-proclaimed “terrible” 2020 with a 113 wRC+. Makes you appreciate the extent to which some of these guys are just operating on another level.

Sorry to make it about fantasy, but it feels terrible when you invested a first round pick in the guy