Adrian Houser Broke the Sinker Mold

“Houser (3-3) picked up the win on Saturday, allowing two runs on five hits over six innings in a 6-2 victory over the Marlins,“ RotoWire News reported. “He struck out ten without walking a batter.”

That’s a straightforward blurb. Nothing really stands out, so I understand if you forgot about it. Adrian Houser himself isn’t a very notable pitcher – his repertoire, which consists primarily of a sinker and an assorted mix of other pitches, doesn’t scream Pitching Ninja material. Against the Marlins a week ago, however, Houser entered uncharted territory in the realm of pitching. Not all outliers are worth mentioning, but this one is:

The graph is messy, but you can still see what happened. Ten strikeouts tied a career-high for Houser, which he reached on August 10, 2019. This time around, though, the journey there was markedly different. For the first time in his career, Houser threw his sinker over 70% of the time. He’d been high-strikeout in some games, high-sinker in others, but the two attributes had never converged so clearly until now. It’s not as if those sinkers were setting up a different pitch, either. Of the 10 strikeouts Houser collected, eight came from the sinker, while the remaining two came from the changeup and the curveball. For the most part, one pitch bookended each plate appearance.

This is remarkable if you know at least a smidgen of pitching. For one, the sinker isn’t a strikeout pitch! Its intended purpose is to induce grounders from hitters, not collect whiffs. Second, unless you’re a reliever, who throws a sinker or any one pitch that often? You’d imagine that hitters would catch on at some point. Yet Houser emerged relatively unscathed. The home run, double, and single that led to two earned runs weren’t even recorded off his sinker.

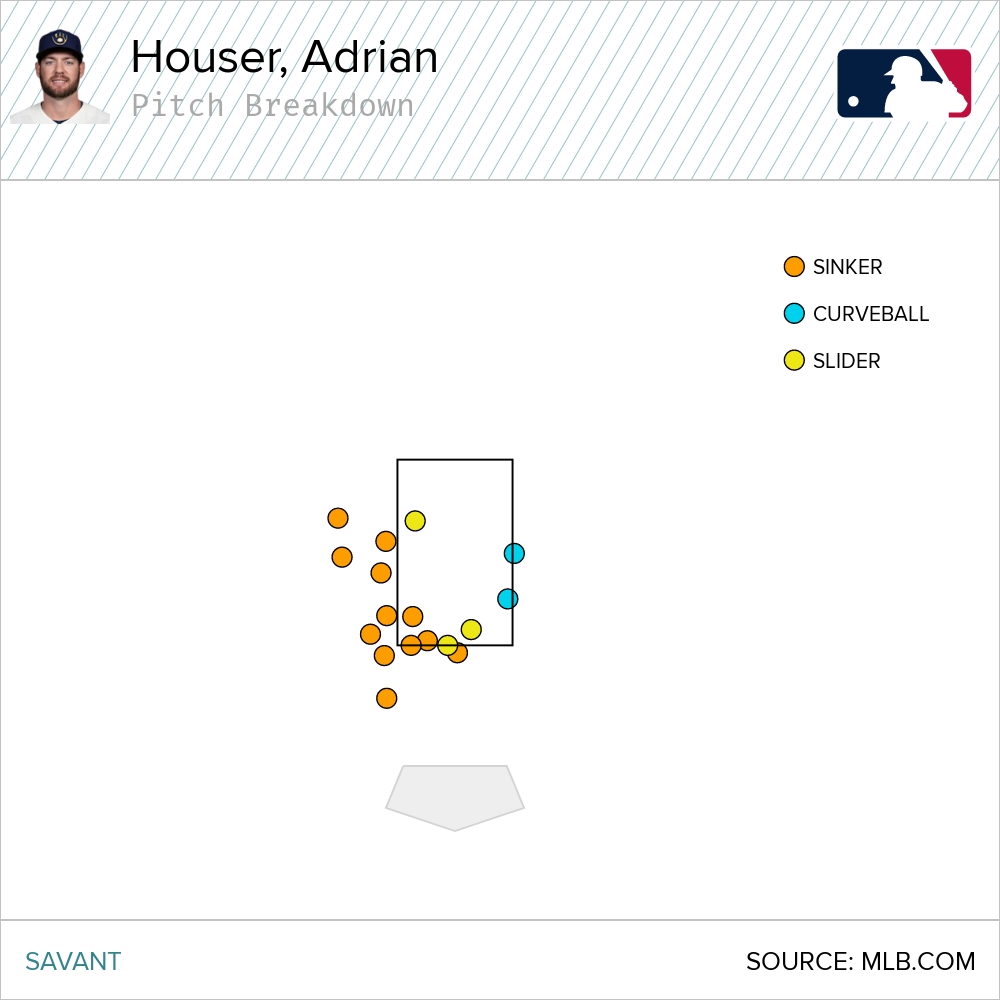

The Marlins’ offense isn’t spectacular, but Houser didn’t merely luck into this. Let’s consult the locations of his whiffs from Baseball Savant:

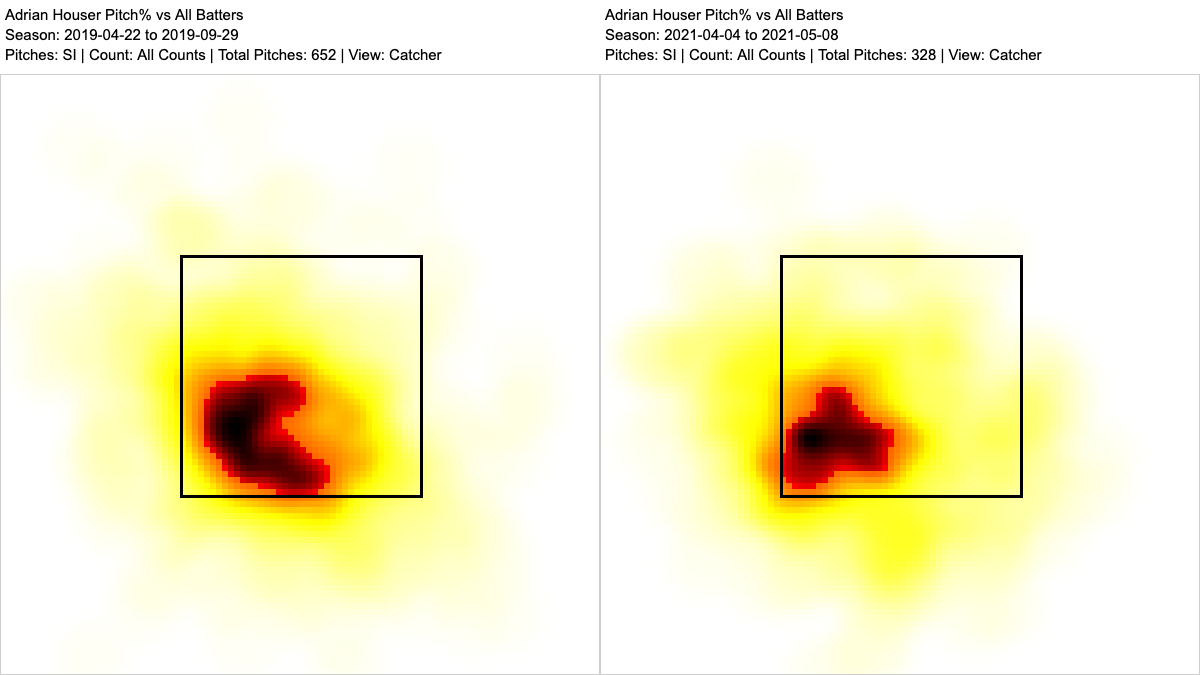

Three sliders, two curveballs, then a whole bunch of down-and-in sinkers to righties. Some are more waist-high, but overall Houser did an exceptional job at avoiding the heart of the zone. Now, unlike high fastballs, throwing sinkers to those locations isn’t a league-wide trend. The percentage of sinkers there has hardly budged over the years. But Houser has made it his own. Using our heat maps, consider the change between 2019 and 2021:

Over time, Houser has shifted his focus from the bottom of the zone to that inside edge. Is there any obvious benefit in doing so? There’s a fine line between a sinker that’s effective and one that isn’t. The way he used to locate, Houser set himself up for potential danger, especially if opposing batters decided to swing. The old location corresponds to zones 5 and 8 of Savant’s Gameday Zone; the new one corresponds to zones 4 and 7. Since 2020, when batters pulled the trigger against sinkers in the former zones, they’ve posted a .378 wOBA. But against sinkers in the latter zones, their collective wOBA decreased to .334.

And in zones 7 and 13, roughly where Houser thrived against the Marlins, that wOBA decreases again to .284. Previously, an issue with the sinker might have been that its users, usually adhering to a pitch-to-contact approach, were lobbing it over the plate. Regardless of how effective one’s sinker is at generating weak contact, hitters have demonstrated their capacity to punish such pitches. Instead, Houser is throwing his with the mindset of a strikeout pitcher, venturing outside the zone to fish for whiffs.

Aiding Houser’s quest is the characteristics of his sinker. Check out how they’ve evolved over time:

| Year | Velo | Hmov | Vmov |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 94.4 | -8.5 | 3.7 |

| 2020 | 93.4 | -8.8 | 3.2 |

| 2021 | 93.5 | -9.3 | 3.1 |

He’s lost a tick of velocity, but that’s no big deal when he’s added nearly an inch of arm-side run. That’s perhaps what allows Houser to befuddle hitters and corner them into uncomfortable counts without having to throw simple strikes. A potential bonus: The spin direction of his sinker deviates as it reaches home plate, suggesting the influence of seam-shifted wake. Not all seam-shifted sinkers gain additional movement – in some cases, an axis shift occurs without it – but it’s plausible in Houser’s case. He got away with throwing his over two-thirds of the time, after all.

Still, everything so far doesn’t quite capture Houser’s success against the Marlins. We need to note that in tandem with recording a career-high 12 whiffs with his sinker, he also recorded a career-high eight strikeouts. The second accomplishment required him to rely on the pitch in two-strike counts.

Why is that interesting? In general, pitchers with sinkers tend to hold back in those counts, opting for a different put-away pitch against hitters. As an example, here are five pitchers who are throwing sinkers about as often as Houser is this season:

| Pitcher | TS% | Non-TS% | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jake Arrieta | 53.1% | 67.5% | 14.4% |

| Zach Davies | 57.6% | 56.7% | -0.9% |

| Sean Manaea | 45.9% | 61.0% | 15.1% |

| Brady Singer | 45.1% | 67.0% | 21.9% |

| José Ureña | 34.4% | 49.3% | 14.9% |

With the exception of Davies, the other four pitchers significantly lower their sinker usage in response to two strikes. Now, you could argue that this sample is flawed because it contains pitchers whose rates are exceptionally high. To check, I randomly selected five pitchers from those who’ve thrown at least 100 sinkers and found that the mean decrease was 7.7 percentage points. The number isn’t as dramatic as before, but there’s enough evidence to say that a general difference exists.

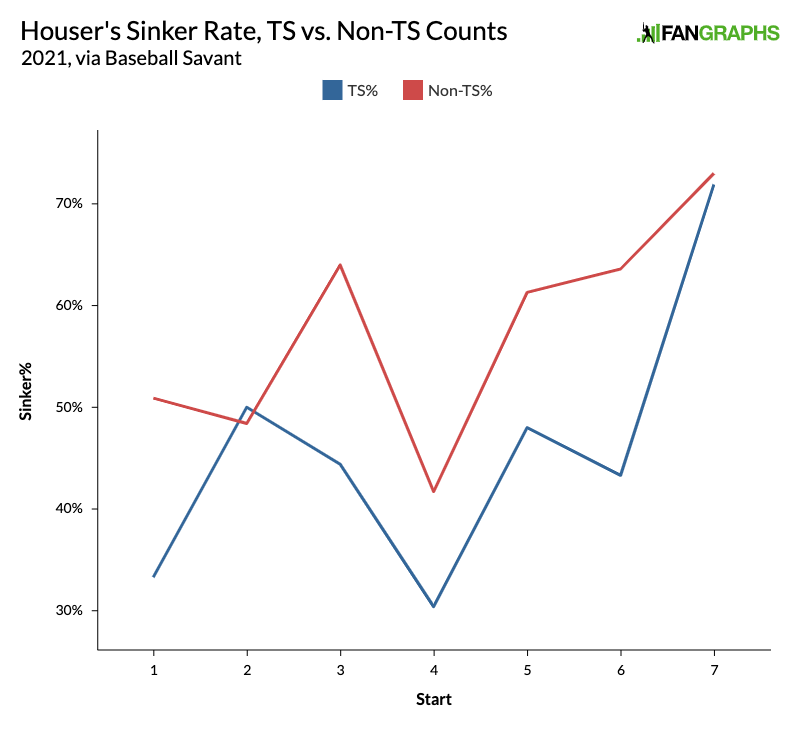

When Houser took the mound on Saturday, he completely flipped this script. I went back to every start he’s made this season and recorded his sinker rate in two-strike counts and non-two-strike counts, then plotted them. The rightmost start is his most recent:

It makes sense that both rates mirror each other. If you’re throwing fewer sinkers in non-two-strike counts, you’re probably throwing fewer sinkers in two-strike counts, and vice-versa. But a gap between those rates has always existed for Houser this season; save for his second start, the two-strike rate has been lower. Saturday against the Marlins, however, Houser responded with unexpected volume and aggression. That seems significant, at least somewhat.

I’m afraid I’ve gone too long without actually showing Houser’s sinker in action. To make up for that, here are some glorious GIFs. How do you demoralize a hitter with just three sinkers? By starting with one that’s perfectly placed, of course:

Not much Chad Wallach can do. Here’s strike two:

Houser misses his down-and-in target, but the pitch’s movement is so nasty that it elicits a big whiff anyways. At this point, you’d think Houser wants to change speeds and/or location. But nope, he goes right back to the sinker for strike three:

Same vicinity, same result. It’s about a hair lower than the first pitch, completely fooling Wallach. That’s the gist of how Houser carved through the Marlins. His confidence in his best pitch was backed up by near-perfect command and a willingness to use it in situations other pitchers might shy away from, such as two-strike counts. He’s thrown plenty of sinkers before, but never to this extent.

Moving forward, it’s a mystery how Houser will use his sinker. Maybe his start against the Marlins is nothing more than an outlier. Or maybe it’s an opponent-specific adjustment, as he’d already faced them once on April 27. But this could also be a watershed moment. Baseball Prospectus analyst Matthew Trueblood once wrote that the sinker doesn’t play (i.e. tunnel) well with other pitches. Maybe the solution is to just throw your good sinkers over and over again!

In a rotation with Brandon Woodruff, Corbin Burnes, and Freddy Peralta, it’s easy to overlook Adrian Houser. A 10 strikeout outing is no 49 strikeouts without a single walk. But during an otherwise normal game, Houser showed his potential by seemingly defying what it means to throw a sinker. He’s been a good pitcher, but never a serious part of our discourse regarding the Brewers’ pitching. Depending on his next few starts, though, that is subject to change.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

You mentioned it may be a team specific approach – any chance that the Marlins are just notably bad against sinkers specifically?