An Investigation Into the Dinger-Filled Rampage of a Reborn Andrew Vaughn

Since July 1, three major league offenses have been head and shoulders above the rest of the field. First, the Toronto Blue Jays, who have benefited not only from a white-hot Bo Bichette, but from having the opportunity to slather a hapless Rockies pitching staff in runs this week. Third in wRC+ but second on this list for editorial purposes: The Athletics, whose offensive run is mostly Nick Kurtz. That’s an exaggeration, but not by much; Kurtz alone is responsible for 2.6 of the vagabonds’ 6.7 position player WAR since July 1, and 39 of their 165 weighted runs created.

The other member of this trio is the Milwaukee Brewers, a team with limited name recognition, whose offense has been propped up by (among other things) a 28-year-old rookie who got cut loose from the Rockies’ minor league system in 2022.

Here’s one of those other things propping up Milwaukee’s offense: Andrew Vaughn, one of the greatest college hitters of the 2010s and a former top-three pick, but also a legendary draft bust as of eight weeks ago.

On June 13, the Brewers traded pitcher Aaron Civale to the White Sox in exchange for Vaughn. At the time, Vaughn was 1.4 wins below replacement level. By that standard, he was literally the least valuable player in the major leagues over the first two and a half months of the season. Behold.

| Season | Team | G | PA | HR | BB% | K% | AVG | OBP | SLG | wOBA | wRC+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | CHW | 48 | 193 | 5 | 3.6% | 22.3% | .189 | .218 | .314 | .231 | 42 | -1.4 |

| 2025 | MIL | 22 | 90 | 7 | 11.1% | 13.3% | .377 | .444 | .701 | .476 | 215 | 1.4 |

That’s like two different hitters. Vaughn was the worst player in baseball for two and a half months, and in just 90 plate appearances, he’s gotten back up to scratch. It’s incredible.

I wasn’t a huge Vaughn guy when he was in his draft year, mostly because if I were running a baseball team I’d rather saw off one of my own nipples with a bread knife than spend the no. 3 overall pick on a short, right-handed-hitting college first baseman. Nevertheless, I thought Vaughn would hit at least a little. What we saw over his four and a half years with the White Sox, though, didn’t even measure up to my realistic worst-case scenario for the former Cal standout.

But 22 games and 90 plate appearances represent just a single frame in this great zoetrope of baseball time in which we spin. To declare Vaughn fixed — or to draw conclusions of any kind, really — from such a small sample of results would be foolish in the extreme. Even so, we can peer into his process and see if anything has changed.

The first thing is that while Vaughn isn’t seeing more (or fewer) pitches in the zone, and hasn’t altered his chase or contact rates to a meaningful extent, he is facing more left-handed pitching. Before the trade, 17.3% of the pitches Vaughn saw came from lefties, against whom he has a 115 wRC+ for his career, compared to 96 against righties. Since the trade, 38.9% of the pitches he’s seen have been with the platoon advantage.

That’ll help, but it doesn’t explain why Vaughn’s wOBA against lefties was .214 this year with the White Sox, and exploded to .510 with the Brewers. Obviously there’s some small-sample flukiness here, but Vaughn’s xwOBA against lefties was .270 before the trade and is .454 after.

One side effect of this newly lefty-heavy diet is that the percentage of four-seamers Vaughn is seeing has nearly doubled after the trade. That certainly helps; you know who hits fastballs better than offspeed and breaking pitches? Basically everyone. Vaughn isn’t making more contact, but he’s making higher-quality contact, perversely, by lowering his average launch angle.

| Season | Team | EV90 | maxEV | LA | Barrel% | HardHit% | GB/FB | LD% | Pull Air% | xwOBACON |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | CHW | 105.3 | 110.5 | 15.4 | 13.3% | 48.3% | 0.98 | 16.8% | 13.8% | .399 |

| 2025 | MIL | 106.5 | 108.8 | 9.6 | 14.9% | 56.7% | 1.43 | 23.9% | 20.9% | .477 |

The seven home runs in 22 games get most of the attention, but Vaughn has hit only 21 fly balls of any kind since the trade. (That 1-in-3 HR/FB ratio, by the way, suggests that there will be some regression coming, but I’m not going to rain on anyone’s parade more than I have to.) What we’re seeing here is more consistent hard line drives and fewer popups. Last year in particular that was a problem: Vaughn popped up 31 times, which placed him in the top 10% of the league for IFFB%. He’s popped up only once in a Brewers uniform so far.

The big difference I can identify with Vaughn on either side of his relocation up the shore of Lake Michigan is that he’s swinging the bat harder.

If there are changes to his stance and approach, they’re very subtle. According to Baseball Savant, his stance was perfectly level with the White Sox and has gone to four degrees open with the Brewers. I’ll be honest, I would never have noticed just by looking. It does seem like he’s holding his hands higher than before, but he’s always waved the bat around pre-swing, and he still has a funky leg kick that looks like Elaine Benes dancing.

He’s standing farther back in the box and closer to the plate, with his feet spread farther apart, but only by an inch or two in all directions, and it is making almost zero difference as to where he’s intercepting the ball.

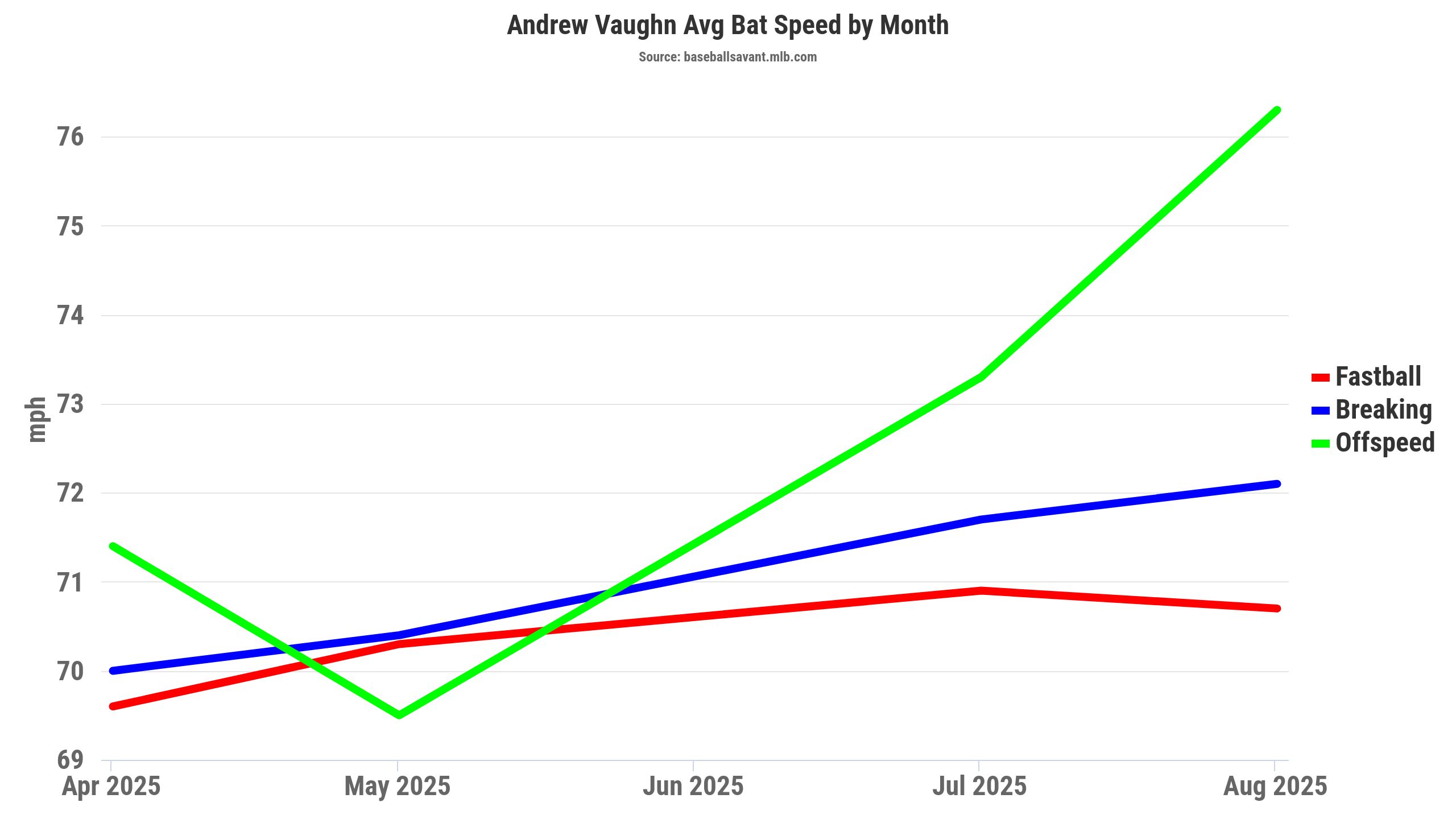

But since the trade, Vaughn has shortened his average swing length from 7.4 feet to 7.2 and increased his average bat speed from 70.0 mph to 71.5. And if you look at his bat speed broken down by month and pitch type, you can see that those gains are coming against breaking balls and changeups.

Don’t get too carried away with the green line; he’s only seen five offspeed pitches in August, and he came out of his shoes the only time he put one in play. This was a ringing 106.9-mph line drive single off Brad Lord on August 3. Though it bears mentioning that on Wednesday night he turned on a 2-0 changeup by Raisel Iglesias and yanked it foul. If that pitch had stayed fair it would’ve been, first, a home run, as well as Vaughn’s hardest-hit ball in play in a Brewers uniform.

Whatever adjustments Vaughn has made, he’s swinging with more force and confidence against secondary stuff. Or the causal arrow is going the other way, and whatever tweaks he’s made have given him the ability to wait a nanosecond longer to identify those pitches and therefore make better contact.

And once that contact comes, it’s more productive; Vaughn hit 27.3% of his batted balls to the opposite field during his last few months with the White Sox. In his time with Milwaukee, he’s cut that mark nearly in half, to 14.9%. More balls to the pull side mean more cheap homers and doubles down the line.

In summary: If I had to propose a grand unified theory of the resurrection of Andrew Vaughn, after 90 plate appearances, I’d say there are three things at work here. First, some small-sample weirdness. While Vaughn has made massive gains in his walk and strikeout rates, and made real gains in his quality of contact, he was neither as bad as he looked on the White Sox nor as Ruthian as he seems now.

Second, the Brewers are feeding him more flattering matchups than the White Sox were. This is what good teams and good managers do: Figure out how to put their players in a position to succeed. Platooning and matchup-hunting have been signature features of the Brewers’ lineup construction for the better part of a decade now, and it’s a big part of why they consistently punch above their weight.

And third, Vaughn has actually sped up and flattened out his swing, which has led to real gains in quality of contact. And while I don’t think he’s going to be a true-talent .700 SLG guy going forward, there’s enough noise here that I feel good about him being a serious offensive contributor to a playoff team. Which was definitely not the case two months ago.

Some guys just need a change of scenery, and while the scenery changes very little between Chicago and Milwaukee, every little bit helps, I guess.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

This is the year that all of the Brewers’ long-shot lottery tickets resulted in powerball – level wins. If you had Dan run ZiPS for Priester, Vaughn, and Collins before this season what they are doing now is probably above their 99th percentile projections.

The Brewers take on a fair number of reclamation projects every year so they have more chances to win but I don’t know that we have seen three hits of this magnitude from them or anyone else for quite a while.

Also interesting to look at where those players are coming from. Pirates (with a brief stop at the Red Sox where Priester already started to look better), White Sox, and Rockies.

The Brewers market inefficiency is fixing players from bad development orgs apparently.

I guess, but they take on so many other ones we don’t think of because they don’t hit this big. Maybe there is more to uncover when they come from these organizations, like Gavin Sheets suddenly being a useful player again but I don’t remember a huge raft of players from the Rockies or Pirates lighting it up in other organizations (although for the Rockies pitchers a lot of that would probably just be not pitching at altitude)

Brewers also acquired Caleb Durbin from NYY. Blake Perkins wasn’t a Yankees draft pick, but the Brewers plucked him from their system with a guaranteed 40 man spot.

They’ve got Anthony Seigler and Brandon Lockridge now too.

Blake Perkins is what it looks like when it works, Vinny Capra is what it looks like when it doesn’t. Pretty much all reclamation projects fall into that range, most of them winding up at about replacement level. Even for the Brewers.

You’re not supposed to get Bip Roberts, AJ Burnett, and Jeff Bagwell from getting players other teams gave up on, and basically no one ever does. (I also don’t think they will continue to play like Roberts, Burnett, and Bagwell but this is how they are playing *now*). This is totally nuts, and it’s too good to be true.

I was today years old when I learned that Anthony Seigler had made the show.

Fair play to the young man!

Bad hitter development orgs, in the case of the White Sox. They can’t do much, but they can develop pitching.

There are reasons for cautious optimism that they’ve made some strides in that department with this year’s crop of rookies: Colson Montgomery, Teel, Quero, and Meidroth. But their track record over the past 15+ years is brutal.

Yeah, let’s not forget Shane Smith on the other side of this equation.

very few look at zips anymore. Its lagging indicator. I’m surprised fan sites haven’t caught up to teams models yet. I know a handful of teams still use reversion to mean zips type models currently but they are few and far between and getting phased out.

Steamer is basically just an aging curve based on initial player performance, but ZiPS uses more granular inputs. Typically MLB teams have access to more stuff than Dan does, and teams have paid Dan to run things for them as a consultant. Most of the stuff they do is more advanced but it’s also not the fault of ZiPS that it is.

Genuinely curious here: what are the models based on if not statistical regression or similarity scores of some type? Have swing decision and bat tracking metrics reached the point of being more predictive (or more rapidly accurate in their prediction) than performance?

They should be more predictive. They are process driven.

In all fairness they identified Priester as someone they liked who was surplus with the org he was with and they gave up what it took to get him the number 33 draft pick and a lottery ticket position player. At the time a number of people thought that overpayed put of desperation. Fangraphs was more neutral than most saying :

“Is that enough to cough up a late first round pick, which is essentially what Milwaukee did here? There are somewhat disparate opinions about the upcoming draft class. I think it’s slightly better than average in the 50-75 range; the tier of player you’d find in a typical second round extends into the third. That sort of depth doesn’t really have an impact on pick 33, but the Brewers’ draft picks are valuable to them because they’re in a smaller market and need to grow their own talent, and their dev group is good at doing exactly that. That’s also part of why this trade should excite Red Sox fans.”

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/prospect-notes-giants-list-updates-the-quinn-priester-trade-and-more/

I thought that deal was a foolish move for the Brewers at the time and I was wrong.

You were not alone. I’m a Red Sox fan and I thought they overpayed (I would stop short of foolish). Most other publications thought that the Brewers gave up far too much but they get the last laugh now.

I felt he was potentially valuable and was surprised the Sox dealt him between injuries and ineffectiveness of other starters. I wanted them to give him an opportunity after what he had shown since being acquired for York. Can’t say it’s like trading an arm to the Rays because the Sox had done a lot of work with him but if he improves in the future look out.

All and all I’m glad for Priester that he was dealt hopefully this is the start of a long career for him after being lost with the Pirates. If the Sox had kept him he probably would have been and up and down guy this season when clearly he deserves more innings and security. The package the Sox got is still a nice package and is better than many of the trade deadline packages for starters. Brewers also made out really well with all of the years of control and how good their pitching program is it will be interesting to see how Priester evolves, he was a mid first round pick for a reason.

The whole series of trades probably is good for the Red Sox since they turned Nick Yorke (whose career seems to have stalled) into a better prospect (Marcus Phillips), plus a couple other vaguely interesting prospects. And I don’t think the Red Sox were any closer to unlocking Priester than the Pirates were, so they didn’t exactly miss out.

But as a pure starter he’s now K’ing 8 per nine innings, walking less than 3 per nine, and still getting a 56% ground ball rate, and when you add it all up you’ve got a guy with 1.5 fWAR in 88 innings (so, probably about 3 fWAR over a full season). And he’s beating his FIP by nearly a run. Which can’t possibly continue but gives you a sense how good a fit he is for a team that runs two shortstops out behind him instead of one (or in the Red Sox’s case in 2024, zero). He’s not the peak version of AJ Burnett but he’s definitely like AJ Burnett, an outcome that would have seemed unthinkable at the time of the trade.

I remember getting downvoted back then for saying I’d rather have Vaughn than Civale. They’ve both done surprisingly well but I still prefer AV.

Vaughn’s time in Chicago had expired.