Andy Pages Is a Perfect Fit

You know Shohei and Clayton and Freddie and Mookie. Teo and Will Smith and Blake Snell and Roki. But do you recall the least heralded Dodger of all? Well, that’s not exactly fair, and I didn’t even name all the famous Dodgers, but here’s the point: I’m writing about a Dodger who isn’t one of the guys who seem to steal every headline.

Meet Andy Pages, the Dodgers’ everyday center fielder. A year ago, Pages was just another hopeful, the latest in a line of plus-bat, where-can-he-play-defense-though options cycling through the corners in Chavez Ravine. Pages’ prospect reports paint a clear picture: a swing built for lift, plenty of swing-and-miss, and sneaky athleticism that exploded after Pages returned from shoulder surgery. In 116 games of big league play, he took over center field (mostly out of necessity — he looked stretched there at times) and posted a league average batting line, though without the home run power that evaluators expected from him.

If you could freeze time there and give the Dodgers the option of having exactly that Pages for the next five years, I think they would have begrudgingly accepted it. Teams as full of stars as Los Angeles’ current squad need role players to fill the cracks in the roster, and outfielders who can handle center and hit at least okay are always in high demand. That isn’t to say that there weren’t encouraging signs – Pages’ athleticism was better than advertised and he showed plus bat speed – but a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and he was already an excellent cog in the machine even without fully unlocking his power.

Flash-forward to this season. Pages started the year playing center and batting ninth. That’s the lineup spot for a complementary piece, a defensive specialist or fourth outfielder. He started slow, with a 70 wRC+ over his first month of play. The Dodgers didn’t have better options defensively, and in fact, Pages looked downright smooth out there, both to my eyes and to defensive model grades. When your team posts a collective 126 wRC+ for the months of March and April (for the months of May and June so far, too — this team is pretty good!), you can live with a below-average hitter playing a tough defensive position, so the Dodgers kept running Pages out there, slow start and all. And that brings us to April 22, when Pages got hot and didn’t stop.

Is that an arbitrary endpoint? No doubt. I don’t think there was anything special about that particular day, but Pages cranked a homer and followed it with another the next day, the start of a molten seven-game stretch good for a 384 wRC+, four bombs, and three doubles. Dave Roberts took note, moving Pages up in the lineup; he hasn’t batted lower than seventh since that offensive outburst.

Now’s the part where we zoom out to the full-season level and see what Pages has become. He’s third among Dodgers in WAR this year and second in homers. His production is almost a dead ringer for Mookie Betts, in fact: similar number of games, similar production at the plate, both at premium defensive positions. The question, to me at least, is whether he can possibly keep this going. Is Pages going to be the first Dodger hitting prospect since Will Smith to carve out an everyday role on this roster of superstars?

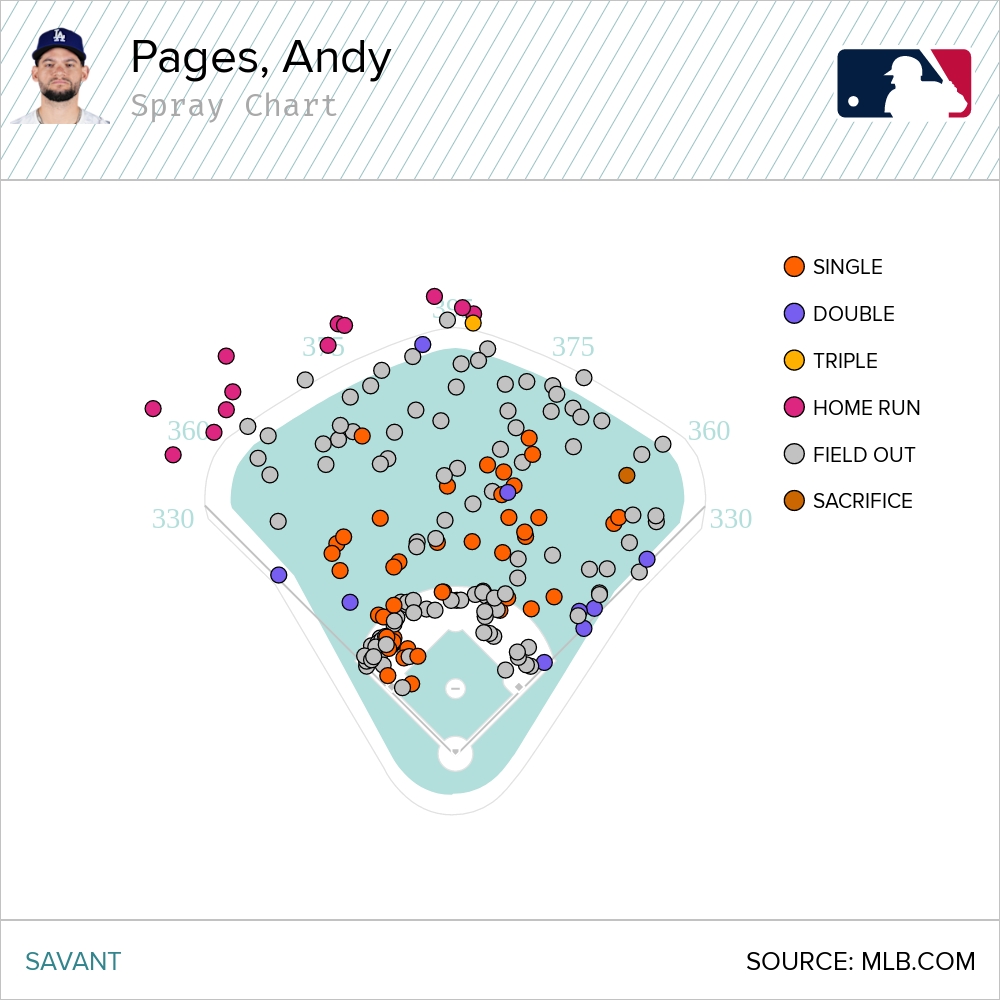

One skill stands out on every dispatch about Pages from his prospect days: his talent for lifting the ball, particularly to the pull side. His swing is designed for it, with a deep tilt that helps him elevate even low pitches. He’s getting the ball in the air a ton, and a quick look at his hit spray chart shows the pull-side element of the equation:

So Pages is one of the pull-happiest hitters in the majors, right? Believe it or not, no! When I look at pull rate, I remove grounders. “Pull power” isn’t about whether you roll over your bad contact or tap it weakly the other way; it’s about what happens when you might actually do damage. Pages pulls 29.9% of his fly balls and line drives. That’s actually below the league average (32.5%), and well below Pages’s mark in 2024 (35.5%). It’s early enough in the season that I’m not particularly concerned with the exact number – a weekend of data could move this around a few percentage points – but Pages certainly doesn’t seem to be an extreme pull hitter.

Maybe he just does a ton of damage on those pulled balls, then. As an instructive example, Shohei Ohtani isn’t particularly pull-happy, but when he does pull the ball in the air, he obliterates it, with an average exit velocity above 100 mph and a hard-hit rate approaching 90%. Only nope, that’s not Pages’ skill either. He’s roughly league average no matter how you slice it – exit velo, hard-hit rate, barrel rate, they’re all saying the same thing.

This is confusing! The normal markers for power aren’t here. Pages doesn’t stand out in any category I look into when I’m trying to hunt for hitters with an approach optimized for home runs. He doesn’t crush his contact, doesn’t go full Isaac Paredes (full Cal Raleigh?) and try to wrap balls around the foul pole. Why is he on pace for a 30-homer season, mostly to the pull side, even without any of the usual statistical signifiers?

The first part of the answer is a surprising one for me – or at least a surprising one for the part of my brain that has been following baseball since I was a kid. I think of Dodger Stadium as a cavernous expanse where offense goes to die, the combination of outfield dimensions and coastal(ish) weather knocking balls down before they can reach the fence and leading to pitchers’ duels left and right. That’s a dead accurate description… for 1996, when Dodger Stadium was the least offense-friendly park in the majors. Today, it plays close to neutral overall, and it’s actually one of the easiest places for righties to hit homers.

You can take your pick between the FanGraphs park factors or the Statcast ones. Take a look at how those two systems have seen Dodger Stadium, both overall and for right-handed homers, over the past decade. Remember, 100 is league average; I’ve highlighted any year where Dodger Stadium was a top five overall park in that category:

| Year | FG Overall | FG RHH HR | Statcast Overall | Statcast RHH HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 96 | 96 | 97 | 104 |

| 2016 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 99 |

| 2017 | 96 | 99 | 95 | 93 |

| 2018 | 95 | 101 | 95 | 96 |

| 2019 | 97 | 107 | 96 | 103 |

| 2020 | 98 | 110 | 98 | 116 |

| 2021 | 97 | 113 | 98 | 125 |

| 2022 | 98 | 111 | 100 | 133 |

| 2023 | 98 | 111 | 99 | 126 |

| 2024 | 98 | 111 | 100 | 126 |

We regress our park factors by more than Statcast does, but the direction of the move is evident no matter which one you prefer to use. Dodger Stadium isn’t a hitter’s park overall, but it absolutely is when it comes to home runs by righties. Chalk it up to wind patterns, climate change affecting the marine layer, interactions between the baseball’s composition and the exact outfield dimensions. Whatever the culprit, there are few parks where it’s better to play as a righty capable of threatening the outfield fences.

With that in mind, we can look at Pages’ season in a new light. It’s not so much that he’s created a devastating bat path that annihilates baseballs to the pull side. He’s just getting the ball in the air early and often, in a park that rewards that very skill. Even better than that, he’s getting the ball in the air without a ton of infield fly balls.

The big benefit of putting the ball in the air is doubles and homers. The big downside – assuming you’ve made contact already – is weak pop flies. When Pages hits the ball at a launch angle of 40 degrees or higher – towering fly balls and popups fit that bill, basically – he has one hit, a bloop single, in 29 batted balls. But those 29 batted balls represent a small subset of his elevated contact. Let’s call those “wasted fly balls” – 80% of hitters in baseball waste a higher percentage of their fly balls than Pages does.

Even that is misleading. The hitter who wastes the fewest fly balls with unprofitably high launch angles is Brendan Donovan, with Luis Arraez close behind. Those guys do it because they don’t hit many fly balls at all. Their preferred contact is a low line drive, so their mishits are high line drives or low fly balls. Donovan’s average launch angle is 9.5 degrees; Pages’ is nearly double that. It follows that he’d naturally hit more popups.

Compare him to the 40 hitters with the closest GB/FB ratios to account for his natural swing loft, and he truly stands out. In this 41-hitter group, only four guys waste their contact less frequently: Bryce Harper, Aaron Judge, Bobby Witt Jr., and Michael Busch. Three of those guys are among the unquestioned best hitters in baseball, while the fourth is off to a splendid start on the back of excellent production on contact. Pages is generating lift without sacrificing a huge chunk of his batted balls to the popup gods. Hitters who can do this generally rock.

Just so we’re all clear, Pages isn’t a right-handed Harper clone. He doesn’t have the same batting eye, the same vicious swing, the same pile of barrels. But he’s a perfect match of player and stadium. He plays in a place where righties can excel by putting the ball in the air. He does that without the biggest weakness of fly ball hitters. Either of the biggest weaknesses, really – his 18.8% strikeout rate is an asset, not a liability.

Oh yeah, and that early-season defensive improvement looks real. With a second year in center, Pages looks natural out there, and his athleticism helps him make up for the occasional bad read or late jump. He’s not Kevin Kiermaier, but he’s at least average in my eyes – maybe better than that, too. At the very least, he’s a young and dynamic defender on a team that increasingly pays older players for their monumental offensive output. Having some defensive flexibility is going to matter more and more for Los Angeles, and Pages is a perfect fit in that sense.

In fact, he’s a perfect fit in a lot of ways. He has a swing built for his home park. He’s a righty who can help balance a lineup with plenty of lefty thump. He plays the position the team needs most. The top of the lineup has a ton of on-base in it; Pages can clean up the bases with some fly balls to left. It’ll probably always come with streakiness, because hitters who get a ton of their value from home runs are prone to long stretches of no production, but that’s just part of the deal when you try to hit home runs.

Is that a star-level player? I mean, it definitely can be. I also don’t think it matters to the Dodgers. “Star” is a definition without meaning. You don’t win because you have more stars, you win because you have more production. Pages fits this team perfectly, raising both its ceiling and its floor. It’s unreasonable to expect a farm system to crank out the likes of Ohtani, Betts, or Freeman with any regularity. The Dodgers have solved that problem by simply trading for or signing those guys. But Pages? He’s home grown all the way, and he’s the kind of player championship teams frequently cultivate.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

As long as he can play center field defense at a league average level–and it looks like he can do that–he could hit like he did last year and play every day, no problem. That allows Edman to handle the middle infield somewhere.

The everyday player setup is excellent and super deep everywhere at six positions, everywhere except shortstop, third base, and center field. While I have some real questions about Betts at shortstop and Muncy at third base defensively Pages looks like he’s made enough improvements to stick in center for a while.

Betts is looking better and better at shortstop at least. Muncy is miscast as a third baseman, but he’s blocked everywhere else so it is what it is.

Muncy needs to get a job somewhere as a first baseman.

I know this is all feels but something about Muncy when it matters just feels right. Stuff that doesn’t show up in a stat sheet. A hitter in the postseason who spits on balls one inch off the plate isn’t something that war can calculate. The ability to take balls I’d imagine is more important in postseason than ever because you don’t ever see the 4-5 guys

I think his postseason wRC+ is virtually indistinguishable from his regular-season wRC+ as a Dodger. Which is really good, because in the playoffs you’re facing Gerrit Cole, Dylan Cease, and Michael King almost a third of the time.

How long are you going to question Betts at shortstop? You bring this up all the time. His defensive numbers have been good to great this year. He is probably only a 1-2 more year solution there but I think everyone but you is pretty happy with Betts currently.

Muncy however is bad and getting worse. He is close to unplayable at 3rd right now.

Betts this season is basically playing like not quite peak Lindor – 122wRC+, 3.7 defensive runs. He needs a bit more power, a few more strikeouts and better base running, and then he’s replicating Lindor. (Oh, and he’s got a broken toe, and lost lots of weight after getting a nasty virus)

It really is quite amazing.

I was shocked to see he had a positive OAA this year when I checked it a couple of weeks ago, although it looks like it was higher then and it’s gone down since I checked it first.

I didn’t buy it last year and I still don’t buy it. If he’s still has a positive FRV (or at least not negative FRV) at the end of the year I’ll buy that at the minimum he can fake it there, maybe more. He’s not making throwing errors like last year and maybe he’ll keep it that way, but he has a really thin margin for error because neither his range nor arm are great there.

Although who knows, maybe he finishes the year at exactly zero, they declare victory and turn it over to Alex Freeland while bumping Betts back to second base.

I’m with you. I love Betts and think it’s incredible that he’s even passable at short. But I doubt that at age 32 he’s actually plus there after being poor last year.

I think a lot of Betts being poor there last year was he moved there halfway through spring training because Lux was so bad that the Dodgers had to move him off short (and the Dodgers have a high tolerance for bad infield defence. See Muncy, M.). This season, that was the plan going in, Betts was on board, and had been using the off-season and spring to get prepared.

I’d imagine that he’ll end the season as an average to a bit below average SS with a wRC+ of 120 or better, which which is a very good season for most players. Just amazing that he’s managed to do this at age 32 and not be a complete embarrassment.

As weird as this is to agree with, I think you are right for the wrong reasons. Betts is slow. To be fair I don’t think statcast calculates speeds correctly. He’s on a no sprint unless it matters order, assuredly. Like he isn’t gonna run out a ground ball. I don’t like it, but smarter men than me thought this up. Do I think he’s 34% percentile in speed? No. Fuck no. But he’s also not fast, probably 60th percentile.

He can get to a peak speed that is above average but he’s a very slow starter. What I have seen from his splits is he is starting faster this year. Almost like the sickness and lost weight made him start faster. But like dollars to donuts he’s faster than yuli gurriel who’s ahead of him.

Brings me back to my favorite so don’t run hard guy. Altuve. Slow as betts. But 8 bolts! No one below him has 1. Yet one of the slowest runners in the game, but top 15 most likely to get to 30f per second. It’s why running stats are all nonsense. Altuve top speed this year is his fastest since 2019. Actually cracks top 8 in peak speed which no one would have guessed. Simpson 1, Buxton 2 etc. I was as surprised as any to see Buxton 2.

An interesting hypothesis. I’m very curious to see how he holds up playing shortstop in August after he’s been charging forward all year.

It’s just not that hard to play shortstop in 2025, especially for a team like the Dodgers who are maybe the best team in the league at shifting. You dont need an Ozzie Smith clone to cover balls hit up the middle when your team can just tell you stand an inch to the side of 2B against hitters who hit the ball up the middle

3/4 of the guys playing SS now would be 3B, 2B or OFs 20 years ago but WAR still give you 2 WAR for standing there for free…credit to Mookie for figuring that out

He and whoever he worked with this offseason figured out that he was going to be best charging forward so he didn’t have to backpedal and that covers up a lot of the things that would normally mess him up, but it also cuts down on his margin for error.

It’s not something I’ve seen a lot of commentary on, but it looks to me like the Dodgers are hanging on to the guys they think will stick higher on the defensive spectrum. They’ve been willing to part with young players who can hit (eg McKinstry or Vargas, who are hitting enough to play elsewhere) but can’t play premium positions.

I think that’s sort of right, but not entirely. The Dodgers and Rays and maybe some other teams believe that if you can play one non-1B infield spot then you can play all of them if you give them enough reps there. Both of them are constantly pushing their infielders to other spots, and sometimes it even works, and when it doesn’t they often just shrug their shoulders and keep doing it anyway (Max Muncy at third base). They just don’t care that much about infield defense.

I imagine the reason why they were willing to move on from Vargas was that he doesn’t hit well enough to justify playing him every day considering that he doesn’t have a position.

I think those teams also like the added versatility as a hedge against injuries or to keep good bats in the lineup while still resting players. It’s definitely valuing offense over defense, which maybe works okay if you also generally start high-K, non-groundball pitchers.

While I agree that the Dodgers care about offense over defense, they also don’t care about individual defense because they’re elite at defensive positioning. And it seems to work, despite the occasional ugly error. They’ve been one of the best teams in baseball by DRS since 2015.

Shortstop is just fine with Betts getting most of the time, then Kim and Edman filling in when needed.

It is left field that is the big problem.