Anthony Rizzo, Joe Maddon, and the Dangerous Play

Over the last decade, Major League Baseball has taken steps to make the game safer for players on the field, not only instituting a seven-day disabled list for concussions but also crafting a pair of somewhat nuanced rules in order to avoid unnecessary collisions both on the pivot at second base and also at home plate.

On Monday, Anthony Rizzo seemed possibly to violate those rules, barreling to the plate in order to prevent Pirates catcher Elias Diaz from throwing to first to complete a double play. Rizzo ultimately succeeded: his collision with Diaz caused an errant throw, allowing two runners to score and turning a likely Cubs victory into a sure thing as the team went up 5-0 in eighth inning.

Did Rizzo actually do anything wrong, though? To answer that question, we actually have to consider two separate rules. To begin, let’s go with MLB’s slide rule first. The rule addresses the allowable — or, as they call it, bona fide — slide, which requires that a runner:

- Begins his slide (i.e., makes contact with the ground) before reaching the base;

- is able and attempts to reach the base with his hand or foot;

- is able and attempts to remain on the base (except home plate) after completion of the slide; and

- slides within reach of the base without changing his pathway for the purpose of initiating contact with a fielder.

Here is Rizzo’s slide.

https://gfycat.com/HatefulAgonizingAustralianfreshwatercrocodile

In terms of the rules as stated, Rizzo abides by the first two conditions; as for the third part, that doesn’t apply in this situation, as the play occurs at home. Regarding the fourth condition, one sees that Rizzo does slide within reach of the base; however, he clearly changes his pathway to initiate contact with Diaz. In this case, the league agreed, confirming that a violation occurred. The gif above shows Rizzo running in foul territory down the line for most of the play before jumping into fair territory right before he reaches home plate. The gif below shows Rizzo’s first step into fair territory.

https://gfycat.com/PointedGargantuanCub

Here’s another view from behind the catcher that shows just how far into fair territory Rizzo ventured for the purpose of making contact with Diaz.

https://gfycat.com/FrighteningSophisticatedDuckbillcat

It’s difficult to get a sense of how this play compares to other similar ones, because the circumstances that facilitated it just don’t happen that often. A search of Baseball Savant for this year reveals just three successful bases-loaded double plays that started with a throw to the catcher and just eight force outs at home with the infield in. Also complicating matters is that the rule above is designed mostly to protect fielders at second base. In those situations, the thrower is facing the runner. Here, Diaz doesn’t have the benefit of having Rizzo in front of him. Whatever the case, it is hard to argue that Rizzo didn’t change direction to make contact with the fielder, which is a violation. It might not necessarily be the precise play the league imagined when crafting the slide rule, but Rizzo’s actions are still illegal under the rule as written.

Even absent a violation, it would be difficult to argue — and perhaps disingenuous to say — that the play wasn’t a dangerous one. I looked through the other 10 plays this season similar to Rizzo’s and there was just a single slide, and that one went right into the plate. While not directly applicable here because Rizzo was not trying to score, this play still violates the safety aspect of the Posey/Avila rule designed to avoid collisions. In fact, Rizzo violated the design of the Posey rule in the exact same manner as he did a year ago. Here was the collision with Austin Hedges.

https://gfycat.com/FocusedDisastrousBirdofparadise

Just like Sunday, Rizzo deviated from his course right near home in order to make contact with Hedges. That collision was more violent because Hedges was facing Rizzo with his knees on the ground, but Rizzo’s movement are the same. He didn’t go knee first into Diaz, but his failure to execute a proper slide is notable in both instances. The rule to avoid collisions notes what makes a proper slide.

A slide shall be deemed appropriate, in the case of a feet first slide, if the runner’s buttocks and legs should hit the ground before contact with the catcher.

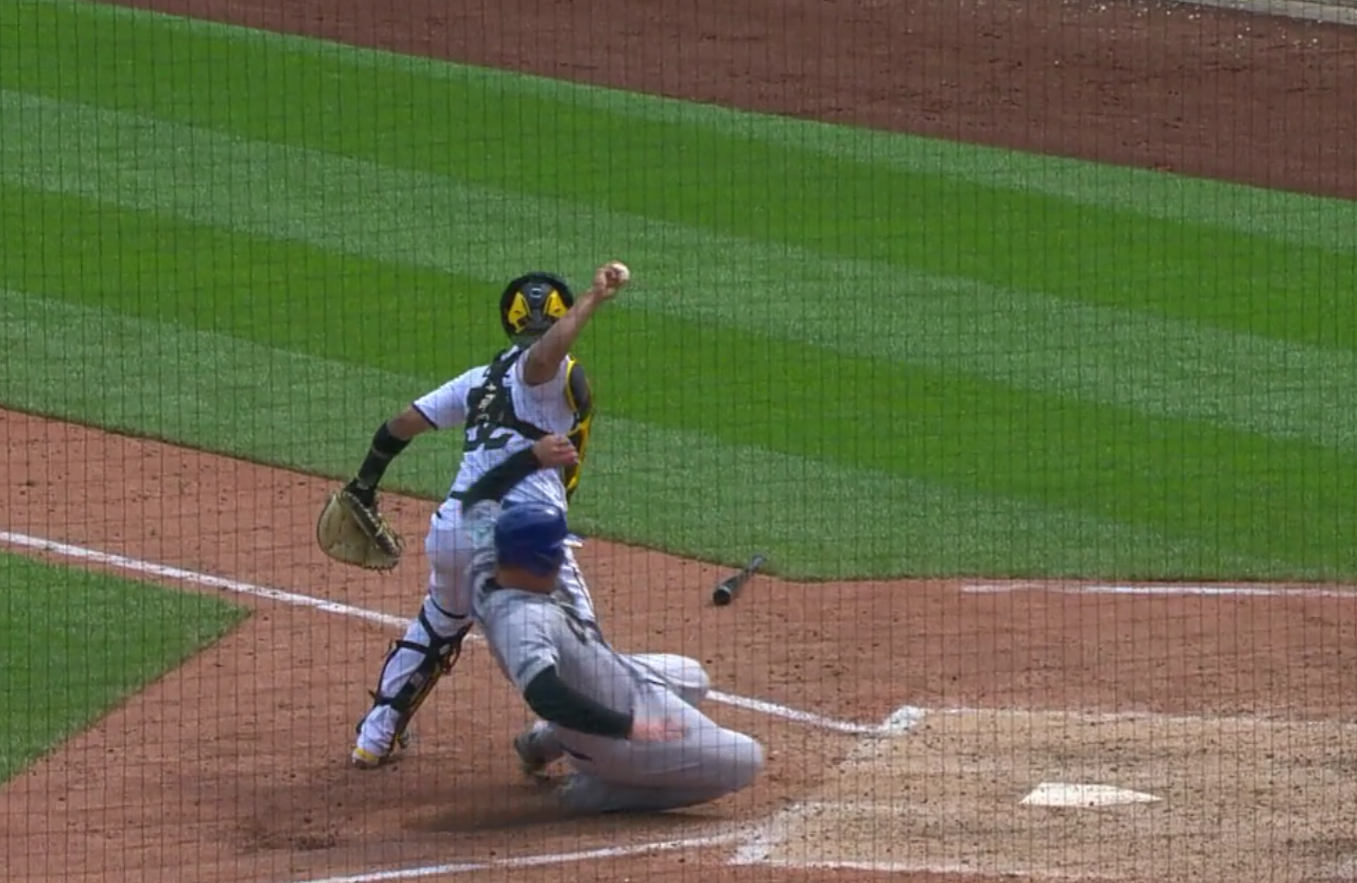

Here’s what Rizzo looked like when he made contact.

Here is the view from another angle.

That’s a dangerous slide and one that would violate the Posey rule if it were applicable. It’s only not applicable because Rizzo was already out and so he instead violated a different rule. MLB, with the help of the players, has tried to make changes to avoid precisely the type of play Rizzo committed. Two plays is hardly a trend or pattern, but given Rizzo’s lack of remorse last season, it can’t be that surprising to see it happen again. Joe Torre indicated Rizzo had violated the rule, but let him off with a warning. After getting that warning last season, here’s what Rizzo said:

“I could have gone in with my shoulder like a linebacker and really took a shot,” Rizzo said. “I went in, kind of last second slide, not really sure where to go, and that’s (Torre’s) understanding of it, too.

Joe Maddon felt the same way.

I’m not going to just concede and just pay lip service to something I don’t believe in. I’m just not going to do it. So I’m really just telling you what I think. That’s what I saw. It was a good baseball play.

Maddon’s comments on the play in question this time seem to reinforce his previous statements on the matter (Full Video from Jesse Rogers at ESPN here).

“That’s how you should teach your kids to slide and break up a double play — the catcher’s gotta clear a path,” Maddon said. “You have to teach proper technique. He’s gotta get out farther, he’s gotta keep his foot on the plate clear because that’s absolutely what can happen. And you know why? Because it happened to me and the same thing happened — the ball went down the right field corner. My concern there was that they were going to attempt to review it in the same way you review it at second base, whereas there’s no base sticking up that you can hold on to.

Just like he was a year ago, Maddon was wrong, and Rizzo again defended his actions immediately after the game in an interview with Jesse Rogers (Full interview here).

“Just playing hard,” Rizzo said. “Never want to try to hurt someone. They’re playing as hard as they can over there, we’re playing as hard as we can over here. You gotta break up a double play. Fortunately, we broke it up, everyone comes out healthy, but I thought it was a good play.”

At this point, why would Rizzo think otherwise? He committed a more egregious offense a year ago, was told by the league what he did was against the rules, and came away not with the sense of having been warned but of having done nothing wrong. The league backed away from enforcing the slide rule almost immediately after implementing it; however, the effect wasn’t that noticeable, as most players simply opted to comply with the rule. Compounding Rizzo’s failure to change, his manager believes the rules that have been enacted to protect players on double plays and at the plate “have no place in our game,” so Maddon likely hasn’t taken Rizzo to task to follow the rules as written.

We now have two similar, dangerous plays committed by the same player in the span of a year. A year ago, the league found Rizzo violated the rules, but ultimately he faced no consequences. While the umpiring crew ruled no violation occurred on the field, the league has said a violation occurred. Rizzo moved at the end of the play to make contact with the catcher and made that contact with the catcher with an unsafe slide that could have been incredibly harmful. The league needs to take action against Rizzo in the form of at least a fine and should probably do the same with Maddon if it wants one of the game’s premier managers to fall in line with reasonable rules to help keep players safe and prevent unnecessary injuries.

Craig Edwards can be found on twitter @craigjedwards.

Here comes Cubs Twitter, y’all.

I’m part of a decently intelligent Cubs group on Facebook. We’ve discussed the play and the vote was split. There’s a decent amount of Cubs fans that will say he’s wrong. I think people are defending Rizzo’s character more than the play… but obviously my fanbase can get pretty protective. I can’t deny it.

Why would anybody defend Rizzo’s character without knowing him personally?

Because Fandom is a strange beast, and an attack on our guys is an attack on ourselves.

Indeed, why would anyone attack it under the same condition?

I’m not sure what you’ve heard of him, but he’s pretty famous locally for spending a lot of time and resources on kids with cancer, he’s known as one of the nicer guys around, etc. I suppose it could be fake, but he comes off as a likable guy, and the fans really like him. I haven’t defended his slide, I’m trying to explain why Cubs fans are defending the guy. He’s got a great reputation in Chicago.

He does have a great reputation in Chicago (rightfully so), but being a good guy off the field has absolutely NOTHING to do with him as a player. He’s developing a much different reputation on the field among fans that don’t have Cubs colored glasses on.

Probably because the dude has helped countless child cancer victims and just won the Roberto Clemente award. An award for the player that “best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to his team”

Great… tiger woods does more charity work than any athlete and he is not exactly the epitome of a role model. Charitable work does not make someone a good person. Cosby did a lot of it to…. Sandusky started a children’s camp etc.

The Cubs cry more than any organization -maddon crying about schedule and travel all year. It’s funny how the Cubs promote “old school” baseball in terms of sliding and hurting a player but when they were thrown at that’s unacceptable. Contreras cried and said he’d ignore the mound visit rule. Lester cried about the nacho fan. This team bitches more than any other and thinks they don’t have to play by the rules. Rizzo is a dirty player. Two years in a row he ignored the rule and could have badly hurt someone because him and Maddon don’t agree with the rule so they chose to ignore it. Disgraceful he wasn’t suspended. A force play makes it even worse. Bush league move by a player who thinks the rules only apply if he agrees with them. Imagine if this happened to Contreras lol. Cubs would be crying non stop

^^^ this guy is a Sox fan… they hate the Cubs more than they like their own team… they’re the most bitter fans in the country

Should I quote all these things I claimed?

Willson saying he’ll ignore the rule because he doesn’t agree with it:

http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-spt-cubs-willson-contreras-mound-visits-notes-20180220-story.html

Lester and Maddon crying about the Slide Rule being properly enforced:

http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/19377486/chicago-cubs-joe-maddon-jon-lester-rip-slide-rule-loss-st-louis-cardinals

Joe Maddon crying about playing a game in weather he didn’t think they should play in:

https://670thescore.radio.com/cubs-joe-maddon-criticize-decision-play-miserable-weather-MLB-office

Joe Maddon crying about the Wrigley Field aspect of scheduling:

https://www.nbcsports.com/chicago/chicago-cubs/cubs-joe-maddons-wrigley-problem-next-years-schedule

Maddon complaining about Memorial Day start time:

http://www.espn.com/chicago/mlb/story/_/id/12950141/chicago-cubs-manager-joe-maddon-unhappy-memorial-day-start

Jon Lester mad about the Nacho Guy who did nothing wrong:

https://deadspin.com/jon-lester-is-not-happy-about-the-nacho-man-1818807336

Anthony Rizzo crying about playing too many games:

https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2018/apr/17/we-play-too-much-chicago-cubs-anthony-rizzo-calls-for-shorter-season

As I said, no team complains more than the Cubs about the rules, scheduling, and emotion/fun of baseball. Pretty hilarious. I could quote 100 more articles.

Growing up in Chicago, I can assure you there’s a lot more complaints coming from the South Side and their miserable fans. There’s a black cloud hanging over the G Spot.

Go ahead and quote any White Sox players complaining about MLB scheduling, and league rule changes stating that they are going to ignore them; I will wait.

This has turned into a Cub love fest in here; defend Rizzo as if you actually knew him. I have no bias in this situation, just knowledge and disdain for an organization that feels they are above the rules of the game.

Also tired of seeing fans point to charitable work as a crutch for kindness when we witness celebrites and athletes time and time again act like POS despite charitable work.

“I have no bias in this situation, just…disdain for an organization” is…well, it’s an interesting statement.

Besides, I don’t think anyone is actually defending Rizzo here.

Uh, there are plenty of people in this chain and the comment section defending Rizzo; hiding behind his “character” that they know nothing about given that they don’t know Anthony Rizzo personally but OK. The Cubs blatantly continue to tell the league they’re going to ignore the rules.

“I’m part of a decently intelligent Cubs group on Facebook. We’ve discussed the play and the vote was split. There’s a decent amount of Cubs fans that will say he’s wrong. I think people are defending Rizzo’s character more than the play… but obviously my fanbase can get pretty protective. I can’t deny it.”

Nobody actually defended Rizzo on the play. Only explaining why other fans like Rizzo and are willing to defend him in this instance because they like him. Do you see the difference?

“We’ve discussed the play and the vote was split.”

Somehow = “Nobody actually defended Rizzo on the play.” Interesting.

Nobody HERE.

well i for one have a brother who tells me that rizzo is a regular at his restaurant and he’s chummy, polite, and classy. something that anyone who works in the industry knows doesn’t apply to sox fans.

baseball history is filled with players known for their ferocity on the field and their congeniality off. As it should be. You want to make this about Rizzo’s character. It’s not; it’s about what he did.

“I have no bias in this situation, just knowledge and disdain for an organization that feels they are above the rules of the game.”

Yes, I’m always looking for more unbiased Cubs opinions from the guy who predicted that Kris Bryant was going to be a bust and that Kyle Schwarber would never recover after his poor start in the 1H of 2017.

thats a lot of crying youre doing about the cubs

The Memorial Day article has this gem from Maddon: Joe Maddon says that “just because something has been done a certain way in the past doesn’t mean it’s right.”

there you go. Joe would be wise to apply this same logic to the plays in question, and recognize the danger his own players could face.

There are indeed other examples, Rational Fan. One that comes to mind is Javy Baez complaining that he flubbed a grounder b/c of white signage behind home plate at Busch Stadium – then he and Chris Bosio claimed that the Cardinals messed with the signage deliberately to hurt the Cubs (which was provably false – the signage was the same for both teams).

assuming he is, you didn’t make even a feeble attempt to argue against his very specific points.

Don’t forget last year when Chris Bosio and John Lackey basically accused Eric Thames of taking PEDs.

Forgot about that one. That after the Cubs whined non-stop when rumblings started to take place surrounding arrieta’s remarkable turnaround and physique. Once again confirming that when the Cubs do it, it is ok

A lot of [people here talking about which fan base cries the most, I wish there was more talk about the play itself. I can see how the HP ump could have missed the call, given his angle, but I can’t see how the folks missed it that do the replay reviews. Unless they somehow didn’t have access to the view from behind HP going up the 3B line (3rd GIF above). I wish I had the audio of the Cubs TV broadcast feed as I would have loved to hear how they described the play and whether they admitted Rizzo’s slide should have been ruled interference or not.

I say this because I saw a replay of Musgrove’s slide into Baez 2 days later and the Cubs announcers were screaming “double play”.. “double play” because they believed that slide was clearly illegal. I was wondering if they were fair on both accounts, or just Cubs homers.

Also, I found Maddon’s comment that Diaz should have cleared a bigger path completely ludicrous. He took a full step forward out of the front of the batter’s box to make the throw. What does Maddon want him to do, run up to the pitcher’s mound and make the throw? He’s trying to make a double play and doesn’t have time to do all that. Diaz did it EXACTLY RIGHT, and Maddon is a moron to suggest otherwise.