By the third inning of Lucas Giolito’s start last night, a pattern emerged. The Pirates would attack him with lefties — they started seven left-handed batters — and Giolito would counter with his changeup. Cole Tucker, for example, faced three straight changeups after falling behind in the count 0-1. He managed to take the first one, but the second and third proved irresistible, and he fruitlessly waved at strike three:

By itself, there’s nothing remarkable about that sequence. Of course righties go to their changeup to combat opposite-handed pitchers — it’s only natural. Giolito has a good changeup, too. Why not use it? But these changeups were indicative of a larger trend, one that you could hardly avoid seeing last night as Giolito rampaged through the Pirates’s lineup on his way to a no-hitter: Giolito’s changeup is his best weapon, and he’s learning to trust it.

If you take a look at our Pitch Values, this is hardly a surprise. Giolito’s changeup is his most valuable on a per-pitch basis. The only year of his career it hasn’t produced better-than-average results was his 2016 cup of coffee in Washington; aside from that, it’s been a trusty companion, even when he wasn’t the pitcher he is today.

This year, however, he’s leaning into the pitch like never before. He threw 78 pitches to left-handed batters last night, and 36 were changeups. That 46.2% changeup rate was the third-highest he’s thrown in a single start. Four of his top five changeup rate starts have come this year:

Changeup%, vs LHB, By Start

| Date |

Lefty CH% |

| 7/6/19 |

50.0% |

| 7/29/20 |

47.5% |

| 8/25/20 |

46.2% |

| 8/4/20 |

41.3% |

| 8/20/20 |

40.8% |

In fact, he’s increased his usage of the pitch every year of his career:

Changeup%, vs LHB, By Year

| Year |

Lefty CH% |

| 2016 |

12.6% |

| 2017 |

20.3% |

| 2018 |

21.2% |

| 2019 |

33.2% |

| 2020 |

38.3% |

Last night, that changeup usage paid off. He drew 13 swinging strikes on the pitch, a career high. He threw high fades, like this pitch to Tucker that ended the eighth:

He worked it below the zone, far too tempting for Jarrod Dyson to hold back:

Even when he left one in the zone, the deception, speed change, and movement were too much for Gregory Polanco:

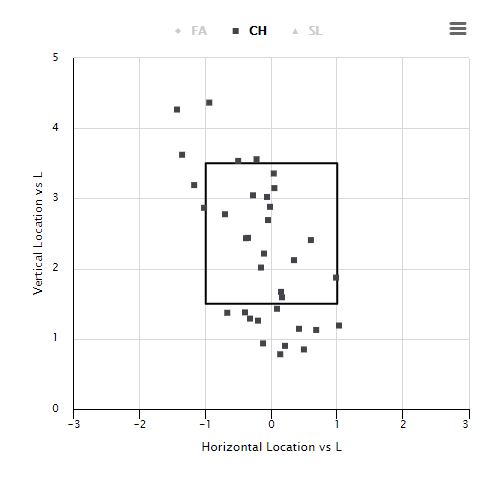

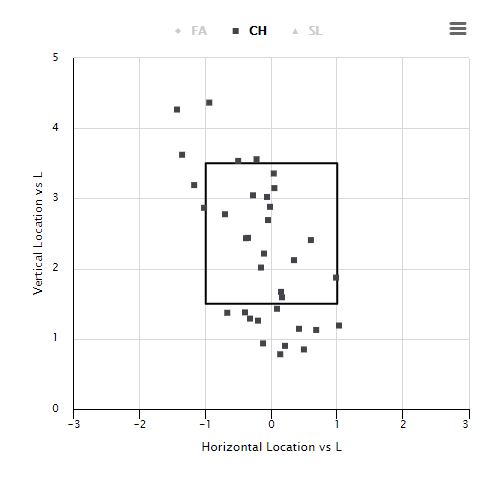

Those three locations — really two locations, because the pitch to Polanco was probably the same rough idea as the one to Tucker — were the plan behind all of his changeups last night. Up and away, below the zone, or misses that drifted over the plate:

While the changeup served to finish lefties off, it also helped set up Giolito’s fastball, and vice versa. Miss a changeup away, as JT Riddle did here:

And you might still be thinking soft-and-away on this hard-and-in fastball:

That was a perfectly-located fastball for the situation. On 1-2, there’s no need to stay in the zone, and the downside isn’t hard contact but simply a ball or potentially a foul. Maybe a batter can make contact with that pitch, but it would take a superhuman effort to drive it to the outfield, much less over the fence.

Better fastball location has been a key to Giolito’s improvement, and he’s taken another step forward in it this year. In 2019, he made significant strides by simply throwing more strikes. He threw his fastball in the zone 57.3% of the time, a career high and four points higher than the overall league average. That aggressive approach put him ahead in counts and kept the pressure on hitters, but it came with a downside: he left 9.1% of his fastballs middle-middle (the league average was 8.2%), and as you might imagine, those pitches got hit hard.

This year, he’s dialed his zone-hunting back; he throws strikes at a roughly average rate. That’s come with a huge benefit; he’s cut his middle-middle percentage by two points, now 7.1%. That doesn’t mean he never misses, but there are fewer opportunities for hitters to take big hacks at centrally located pitches. Batting isn’t easy; you can get a good pitch to hit and still end up like Bryan Reynolds here:

Leave a pitch there often enough and the batter is sure to win eventually. But Giolito gave the Pirates only three such cookies last night. Fail to cash in on those, and you’re looking at a steady diet of unhittable changeups and painted fastballs. It’s simply a numbers game, though the numbers won’t always work out as well as they did against the Pirates. Dropping from 9% to 7% is roughly one fastball per game the opposing team doesn’t get to take a cut at, and in the long run, that adds up.

In fact, that’s my main takeaway from last night. No one has ever been a good enough pitcher that you should expect a no-hitter in a given start. Baseball simply doesn’t work that way. Last night, however, Giolito gave himself a phenomenally good chance to hold the Pirates hitless. He started early; he got behind in the count 1-0 only seven times and got ahead 0-1 17 times.

From there, he mostly gave the Pirates only bad choices. They couldn’t help but comply; they came up empty on 41% of their swings against his fastball, and that’s the easy one to hit. They whiffed on 56.5% of their swings against his changeup, and 72.7% of their swings against his slider when he deigned to throw it. He drew 30 swinging strikes last night, the highest total and percentage of swinging strikes for any starter this year. They’re a bad hitting team, one of the worst in baseball, but he also never gave them much of a chance.

That’s not to say the start was flawless. Thirteen strikeouts in a complete game means at least 14 balls in play, 14 chances for something to fall through. That’s a simple truth of pitching: you can’t avoid rolling the dice on a few balls in play, no matter how dominant you are.

One of the sticking points about sabermetric analysis of baseball is the role of luck in the game. The argument in favor of it is pretty clear: results follow a normal distribution in many cases, and the worst team beats the best team some amount of the time. No one would argue that baseball is deterministic. Thinking of the sport as a series of coin flips, though, robs it of some inherent drama. Is a no-hitter as impressive if it’s not a triumph of pitching but rather a string of 50/50 decisions coming up in Giolito’s favor?

I think people misunderstand what sabermetricians mean by luck. I certainly don’t think of it the way I see it popularly described. Sure, batted balls are inherently a roll of the dice. Microscopic differences in initial contact can be the difference between a liner in the gap and a screamer directly at a fielder:

Think of it this way, however. Have you ever woken up in the morning and felt an extra spring in your step? Ever thrown a ball around and thought “Wow, my arm is accurate today”? Of course you have, because it’s a natural part of the human condition. Do you have any agency over when it happens? Some, perhaps — you’re less likely to wake up bright-eyed and bushy-tailed after a night of partying — but for the most part, it’s simply a feeling you get in the morning at random, waking up on the right side of the bed, so to speak.

Lucas Giolito woke up on the right side of the bed yesterday. The Pirates hitters didn’t. Play that game, in those exact conditions with those players at that exact moment, 100 times, and you wouldn’t get 100 no-hitters. You would, however, get sheer dominance. Giolito wasn’t simply “getting lucky” when he blew fastballs by hapless batters, or went fishing with his changeup and hooked batters 13 times. He was in the zone, executing all three pitches and rarely missing location, he and James McCann divining hitters’ thinking and twisting them into pretzels.

Call it luck if you’d like. It’s clearly not an average day for Giolito. Were he to pitch like this every time out, he’d be the best pitcher in baseball. But in the moment, I think it’s unfair to say he was simply “getting lucky.” On his best days, Giolito is capable of such a display. Those best days don’t happen frequently, of course. They happen far less often than his average days, and the average days are important, because seasons are built on average days.

For me, though, it’s a reminder of why it’s such a joy to watch a great pitcher. In the long run, randomness will prevail. Giolito will have some good starts and some bad starts, and the sum of his efforts will go down into statistical record. The average of those starts is what you can expect to see from him in a random game. But it’s not what you’ll actually get from him on a given night. Any start you watch could be the one where he’s feeling it, where he “deserves” the kind of performance we just saw, and there’s simply no way of knowing if you’ll witness it until you watch.

Last night was a fluke, in a mathematical sense — most of the time, Giolito isn’t that good. And yet, it was no fluke. If he could replicate his true talent level from last night, not all his high and low points but simply his form at that exact moment, he’d break baseball. It won’t last. Next time out, he might be great again or might be average, and there’s no way to know until it happens. That’s the joy of a great pitching performance. It might not be likely, but when it happens, it feels almost inevitable — give or take an assist from Adam Engel.