Author Archive

Imagining a Socially-Distanced Baseball

Last Friday on Effectively Wild, Meg and Ben (Not me! Curse you, Lindbergh, for your recognizable Ben-ness!) answered a question that several readers had asked. How, the readers wondered, might baseball exist if everyone involved in the game were required to remain at least six feet apart at all times?

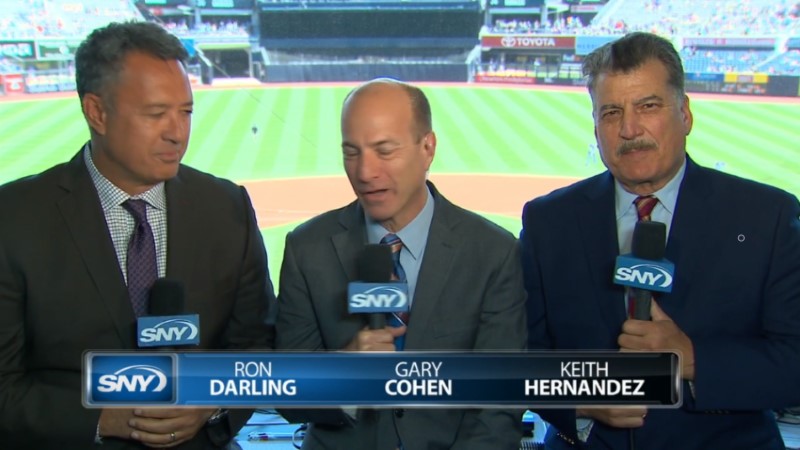

It’s a silly question, really; they’re not going to play baseball with social distancing. But a question being silly has never stopped me even when there was baseball to write about, so let’s brainstorm. To figure out what would need to change if baseball wanted to be compliant with the new COVID-19 world we’re living in, I decided to choose a game from last year and watch for what we’d need to change. I picked a random date — June 11, 2019 — and selected the first game available, the first game of a Mets-Yankees doubleheader.

As a recap, Meg and Ben took their best shot at figuring out what might happen. They considered ghost runners or Statcast-estimated speed splits to each base. They considered eliminating the running game entirely. They noted that an automatic strike zone would likely be necessary to remove the umpire from his current position. Additionally, they covered some easier spacing dilemmas — only one reliever up in the bullpen at a time, a mostly-empty dugout with players remaining in the locker room until needed, and automatic reviews that would allow an umpire to stay further from the action.

With those ideas in mind, I started watching my random game. Some of the personal contact would be easy to fix. For example:

We’re Managing the (Fake) Brewers!

Good news, everyone! Our crowd-managed Brewers have started the season. Not well! Not well at all! But they’ve started the season. Game 1 was an absolute blowout; the Cubs put up 14 on the Brewers, including five runs against Josh Hader (on three walks, a hit by pitch, and a grand slam by Javy Báez). Our batters weren’t up to the task, scoring only three runs. Yu Darvish went eight innings and struck out 10 Brewers.

One game isn’t enough to say anything about this team, but it was an ugly one. Christian Yelich, Justin Smoak, and Avisaíl García all went hitless, and the team didn’t put enough pressure on Darvish to even make any interesting baserunning decisions. The pitching staff walked 10 and hit three while striking out only four Cubs, a desultory performance to match the offense’s slow start.

But it’s just one game. It’s time to start thinking about the rest of the season. First, let’s review the decisions we made last time. We had a few management sliders to move. You voted for aggressive baserunning, frequent infield shifts, and quick pitching hooks. The only place where there was a confusing result was on pinch hitting, where slightly aggressive pinch hitting was first, slightly conservative pinch hitting was a narrow second, and neutral tendencies came in third. I decided to resolve this by leaving pinch hitting pretty much middle of the road. Read the rest of this entry »

An “Opening Day” Viewing Guide

It’s Opening Day! Or, well, it would have been Opening Day. It was Opening Day? The semantics are still unsettled. In any case, today is a day when I’d normally block off my entire calendar and watch baseball — glorious meaningful baseball — all day long. The global pandemic hasn’t stopped my yearning for that yearly ritual; if anything, the grim reality of our current predicament has made me long for baseball more.

Luckily for me and you, MLB is doing its best to make it feel like baseball is still here. The league has assembled a broad slate of games across several platforms that will let you watch all the baseball you can handle. There are 35 broadcasts in all:

Tomorrow MLB presents #OpeningDayAtHome – a full slate of 30 games nationally available across various platforms, including digital streaming and social media, creating a full-day event on what would have been Opening Day. pic.twitter.com/NGd39zk883

— MLB Communications (@MLB_PR) March 25, 2020

There are so many games, in fact, that you can choose your own adventure. Or, if you’re so inclined, you can let me choose your adventure. Here are a few slates for various types of fan.

World Series Drama

If you want to watch the highest-stakes games available, you’re in luck. Start your morning off with an appetizer: the 2013 Pirates/Reds Cueto game, which I wrote about here, in Spanish on Twitter. It’ll be early, so brew a coffee, eat some cereal, and listen to awesome announcing and echoing Cueto chants. There are no World Series stakes in this game, but it’s the best of a thin 8:30 ET slate if you want drama.

From there, it’s nothing but the hits. Head to Facebook for Cardinals/Rangers Game 6 (2011 World Series) at 11:00. Knowing what happened doesn’t make it any less ridiculous that the Cardinals were down to their final strike twice — in consecutive innings! — and stormed back to win in 11 innings. The level of play wasn’t pristine — the teams combined for five errors, and that doesn’t count Nelson Cruz’s Family Circus routes in right. But you’re not here for crisp play, you’re here for drama, and this game delivers. Read the rest of this entry »

Noah Syndergaard Tore His UCL, and It Sucks

Baseball news is coming in drips and drabs these days, which makes sense — we’ve all got bigger things to deal with at the moment than contract extensions and teams with unsettled rotations. Unfortunately, that means that when there is baseball news, it’s likely to be bad, and yesterday was no exception: per Jeff Passan, Noah Syndergaard has been diagnosed with a torn UCL and will undergo Tommy John surgery tomorrow.

Regardless of when or if the season starts, this is obviously terrible news for the Mets. The NL East is nasty and brutish, and the 2020 season, should it happen, will be short. Every win is — well, baseball is never a matter of life and death, and that’s never been more clear than in recent weeks. But every win is monumentally important. Over a full season, replacing Syndergaard’s 4.6 WAR projection with Michael Wacha’s 0.6 WAR projection would be a tough blow, and that’s before considering which minor leaguer will be picking up Wacha’s innings.

Those four wins hurt; over the full year, they drop the Mets from roughly even with Atlanta and Washington to roughly even with the Phillies, turning the division into a two-tiered race. In fact, now that the Mets are without Thor’s services, they’d prefer a shorter season, because they’re decidedly underdogs at this point. As Dan Szymborski recently illustrated, a half-season gives underdogs a fighting chance.

Whatever your feelings towards the Mets, this is a disastrous stroke of bad luck. The team is built to win in 2020; Marcus Stroman will hit free agency after this year, Syndergaard will follow him the year after, and many of the team’s veterans are most useful in 2020. Robinson Canó isn’t getting any younger, Rick Porcello and Wacha are only in the fold this season, and Jacob deGrom is only invulnerable to decline until he isn’t. Without a stacked farm system, this might be the team’s best chance for another World Series berth in the near future. Read the rest of this entry »

Let’s Manage the Brewers!

There’s no baseball right now. Heck, there’s no anything right now; Joe Buck is offering to do play-by-play of domestic chores:

I have good news for you –

While we’re all quarantined right now without any sports, I’d love to get some practice reps in. Send me videos of what you’re doing at home and I’ll work on my play-by-play. Seriously! https://t.co/txAGBLPBGz— Joe Buck (@Buck) March 22, 2020

But if you’re in the mood for some baseball, you’re in luck. Brad Johnson of RotoGraphs has organized a 30-person Out Of The Park league with human managers for every team. Partially, some of the fun will be providing updates and talking about team strategy. Candidly, we’re all looking for something to write about, and describing the machinations of our very own team is too good to pass up.

But we can do more. I’m managing the Milwaukee Brewers. Rather than simply tell readers what my team is doing, I’m opening it up to the crowd. We, as a FanGraphs community, will be running the Brewers. Maybe it will work well. Maybe it’ll be a disaster. Either way, though, I think it’ll be a lot of fun.

I’m going to lay out a few ground rules. You’re not getting to vote on whether we should trade Christian Yelich for a bag of nickels. We shouldn’t. There’s no point in taking a vote on that. And we’re not going to legislate the overall direction of the team — we, the Brewers front office, are going to operate under budget constraints while attempting to make the playoffs in a competitive NL Central. Read the rest of this entry »

First Pitch Follies

One of the joys of baseball, and sports in general, is that the narrative arc of the game isn’t preordained. You can’t know when the most important pitch of the game will be before the game starts. This isn’t a TV procedural, where nothing decisive can happen in the first 20 minutes. The visiting team might go up 3-0 in the first inning and never relinquish the lead, or they might rally furiously from down five only to lose in the bottom of the ninth.

Even though the most exciting pitch of the game isn’t a given, one thing more or less is: the first pitch of a game won’t be the most exciting one. That’s partially due to the rules of baseball — no one is on base, and most at-bats take more than one pitch — but the first pitch is unique in its own way. For one, no one swings. Combining the first pitches thrown by each starter in a game, batters swing at 23% of offerings, significantly lower than the 29% overall swing rate on 0-0 counts.

Secondly, it’s almost always a fastball. Sam Miller delved into the thinking behind game-opening fastballs, and pretty much everything from his piece still holds. Pitchers throw fastballs because batters don’t swing, and batters don’t swing because they already don’t swing much on 0-0, and particularly so when they haven’t seen the pitcher throw anything yet.

But batters aren’t static opponents. In 2010, they swung at 25.1% of 0-0 pitches. In 2019, that number was a meaty 29.4%. Strikeouts are rising, pitchers are fastball-happy on 0-0 counts, and batters increasingly can’t afford to hang around waiting for something to hit given the decline in overall fastball usage. Read the rest of this entry »

A Dubious Distinction for Yuli Gurriel

The worst thing you can do when you put a ball in play is hit a popup. That’s the worst thing usually, at least: right now, the worst thing you can do is be playing baseball at all, because you plus the opposing team makes 10 people, you jerk. But most times, it’s hitting a popup.

You’ve seen the reasoning for this before, but I’ll quickly lay it out again. When you hit a popup, you don’t reach base. Per Baseball Savant, balls hit with a launch angle of 50 degrees or higher produced a wOBA of .016 in 2019. Given that an out is worth 0 and league-average wOBA is .324, that’s pretty close to being an automatic out. Want it in a triple slash line? If you hit the ball at a 50 degree angle or higher, you bat .015/.015/.022. That’s ugly.

There’s good news, however. Want to avoid popping up and slamming your bat to the ground in disgust? There’s a simple solution: avoid swinging at high pitches. I’m no physicist, but the relationship between high pitches and popups seems straightforward. Your bat is likely to contact the ball from below, there’s some angle-of-incidence angle-of-reflection magic, and bam, Eric Hosmer is camping under the ball. Either that or you get some Alex Bregman magic:

COVID-19 Roundup: Shortened Seasons

This is the second installment of a daily series in which the FanGraphs staff rounds up the latest developments regarding the COVID-19 virus’ effect on baseball.

Given the speed with which national guidelines on COVID-19 are changing, you could be forgiven for not keeping up with its implications for baseball. Since last Friday, the CDC has recommended avoiding gatherings of 50 or more people for the next eight weeks and the White House asked the country to avoid groups of 10 or more, keep kids home where possible, and avoid eating and drinking in public for the next 15 days.

Meanwhile, major metropolitan areas are settling in for the long haul. The Bay Area announced a Shelter In Place policy on Monday, and New York closed restaurants, bars, and schools until at least April 20; Washington state has announced similar closures of gathering places, with schools set to remain closed until at least April 24. The state of Ohio did the same on Sunday, and Oregon has already followed suit.

So what’s a roundup of baseball news items against that backdrop? It’s insignificant, really. But here we are, on a baseball website, and COVID-19 continues to affect the game. Here are the baseball-related coronavirus stories from the past day. Read the rest of this entry »