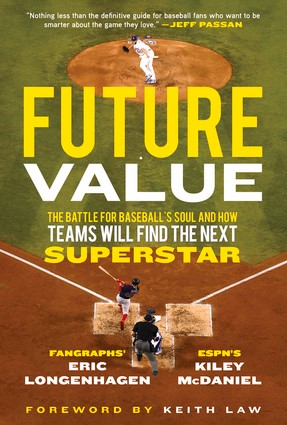

Book Excerpt: Future Value: The Battle for Baseball’s Soul and How Teams Will Find the Next Superstar

Earlier this week, FanGraphs’ lead prospect analyst Eric Longenhagen and former FanGraphs prospect writer Kiley McDaniel released their book Future Value: The Battle for Baseball’s Soul and How Teams Will Find the Next Superstar.

In this excerpt from the chapter “Everybody Wants a Job in Baseball (But Nobody Wants to Die),” presented with permission from Triumph Books, Eric and Kiley discuss the different paths to working in baseball, and how to become a scout – from the tools and skills you’ll need to the people who can help clear the way.

…

Plotting a Path

Depending on what your career goals and timetable are, and despite the fact that everyone in baseball took a unique path, there are lanes to place yourself in to increase your odds at success.

If your goal is to be a GM (this is the most common dream), then you need to figure out what your separating skill will be (you don’t have one right now) and go down the path to be an expert in that area. Increasingly, being an ace scout isn’t a recipe to run a team, so that’s not the smartest way to position yourself for a move up the ladder to GM. You can come up in scouting departments or player development, but be based in the office so you have a management point of view, are getting face time around those people, and are in those meetings. You may need to be a coach or scout as a first step, but know that your path needs to get you into the office sooner than later.

More commonly, GMs come from people who are office-lifer types, who come up as assistants in baseball operations (general contributors across departments), a step up to coordinator or assistant director (managing schedules and interns or entry-level employees, introduced to decision-making meetings), then becoming director of baseball operations (in charge of budgets, rules, running the office day-to-day, pitching in on hiring and higher-level decisions) then assistant GM, where your specialty (running the office, rules, overseeing a scouting or player dev department) is the flavor that your job takes, along with the thing that can headline your résumé for GM.

A sitting GM once described to us that he and his three AGMs are in charge of servicing the various departments (analytics, big league operations, international scouting, domestic scouting, pro scouting, player development). There’s more departments than the four of them, so they’re playing a zone coverage, constantly going between all the areas, making sure each department has what they need to succeed and, ideally, not needing further direction or correction.

Things get a little simpler if your goal is simply to be that director of baseball ops or the rules-focused, behind-the-scenes AGM, as you can focus on being good at your job, networking, and waiting for merit to dictate when the job comes along. GM is tougher because, like head football coaches or CEOs, you can get stagnant, age out, or lose the momentum you had, even though you’re technically getting more qualified every day. Getting a job as someone in a GM’s cabinet is more based on your relationship with them and how good you are at your job, while there’s much more public résumé-building and political machinery behind GM jobs. Every team has three or more people qualified for a GM interview in some way, but the same dozen or so people across the league keep getting interviewed.

This advice also goes for coaches who want to get to the upper levels or big leagues, scouts that want to be the director of the department, or lower-level execs that want to be the farm director. If you want a decision-making role that’s office-based, it’s better to get into the office as early as possible, since you can always be fast-tracked there and play a hybrid role. Many assistant directors of amateur scouting were area scouts or regional crosscheckers. They take the assistant director job to play the role of national crosschecker, which also has an administrative element to get them trained to run a department one day. Keeping personal growth in mind is something you should do, but any good boss will also ask you what you want to do and put you in positions to succeed. In reality, this is rarer than you may think, as people tend to focus on themselves when put in positions of power.

The first job you get to set you on this course isn’t that important, since getting in the door and starting the process of networking and building a track record is more important than having the perfect first step. The one area that’s a little tricky in many organizations is video internships. For more progressive organizations, this could mean being at a minor league affiliate, organizing the video for coaches and players and also playing the part of junior analyst, using development tech like TrackMan, Rapsodo, and Blast Motion and making suggestions in the areas where you’re given latitude to do so. This isn’t a bad first step, as it gets you experience in a clubhouse, working with players and coaches on the development side, a chance to prove/improve your analysis chops, and experience working with widely-used analytics tech that you have to get a job to be around.

With less progressive clubs, this can be more of an eyewash position laden with menial daily tasks, no analysis element, no structure to allow you to shine, nor contribute in view of the front office, and there’s no path to full-time employment unless the video coordinator is leaving their spot. Do well at this sort of job and you may not have learned skills that are transferable into an office or networked with the office types that can help you find your next spot. Paradoxically, succeeding at this job means you might be offered it again, then you’re forced to take it due to lack of superior options and you’re further pigeon-holed without adding diversity of skills, experience, or network to your resume.

Knowing the level of structure around an affiliate video internship and the track record of previous interns getting full-time jobs in an area you’re interested in is key to knowing if that makes sense for you. If it’s more of a wheel-spinning type role, learning coding, publishing research, going to industry events, and working a part-time job to make ends meet is a much better use of your time.

Again, this applies to more traditional clubs. Milwaukee and Houston have made huge use of video and it might be a smart place to start with a team that thinks like them.

Becoming a Scout

As we mentioned earlier, if you want to be a scout, the advice is pretty simple: go scout games. This allows you to both build your library, but also to network and get used to the grind and little details that come with the job. It’s not really fair, but dressing a certain way (performance-material polo and pants), standing in certain places (down the open side for notable hitters at amateur games, behind home otherwise), having the right things in your bag (Accusplit stop watch, decent-looking notebook like a Moleskine), and how you chat with scouts are all indicators to them if you’re the type to either help them or to recommend to their club or rival teams looking for scouts. Remember that you’re surrounded by people who are observant and traffic in gossip for a living. Helping scouts is most often done as a “bird-dog scout,” or a lightly-to-unpaid scout that lets the area scout know about games they aren’t able to attend. This could be as simple as cheating off the radar guns and reporting velocities to the area scout, or a retired scout that sees second-tier players to stay busy.

As we mentioned above, writing reports is a key part of this process. The process of taking notes is a step up from just watching, as it obviously forces you to be critical the whole game. It’s hard to fully explain, but writing a report that formally combines the notes with a full opinion and a projection for the player forces you to think even more critically about what you saw and then project years into the future and pass official judgment (with a Future Value, or something like it) that can later easily be proven to be right or wrong. This may be the most important aspect of the process for aspiring scouts, along with making sure that scouts are seeing these reports. It can be hard to do this without having seen a layer of players age from their teens into their physical primes, and that takes time.

Scouts and executives seeing these reports is key because you’ll get feedback both on how good the reports are and how to fix the ticks that give away that you’re still a beginner, while also expanding and deepening your network for when a job comes along that fits you. This is tricky, because scouts don’t start their day hoping to find an aspiring scout with nothing on their résumé and give a few hours to this kid. You have to be dogged but also not annoying.

Kiley found it served him well to not initiate conversation with any scouts when he started out, just go to games, stand around where the scouts stood, and wait for one to get curious and ask him why they’ve seen him four times this week. One scout said they saw Kiley more than their wife that week, so they had to know why he was following them. This is a bit of a long-term play, but it paid off because most of the scouts in Florida knew Kiley within a year or so and there wasn’t a basket of cringe-worthy stories going around to make other scouts hesitant to talk to him. Stories were going around about many of the other aspiring scouts in the area; these awkward times are common, but the key is to not let them last too long.

…

For more information on Future Value or to order a copy please visit Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Bookshop.org or Triumph Books

The book is a great read. It provides a ton of insider information that the average fan would not even think about. It inspired me to pre-order the new book written by this publication’s foreword, Keith Law, “The Inside Game”.