Brad Hand, Fly Ball Enthusiast

If you don’t look too closely, it’s easy to see Brad Hand at the top of the ERA and WAR leaderboards for relievers and shrug. He’s an excellent reliever, of course; he hasn’t had an ERA above three since adding a slider after the 2015 season. When Cleveland traded Francisco Mejia for him (and Adam Cimber) last summer, they weren’t adding two generic middle relievers; Hand was the hottest commodity on the relief-pitching market for a reason.

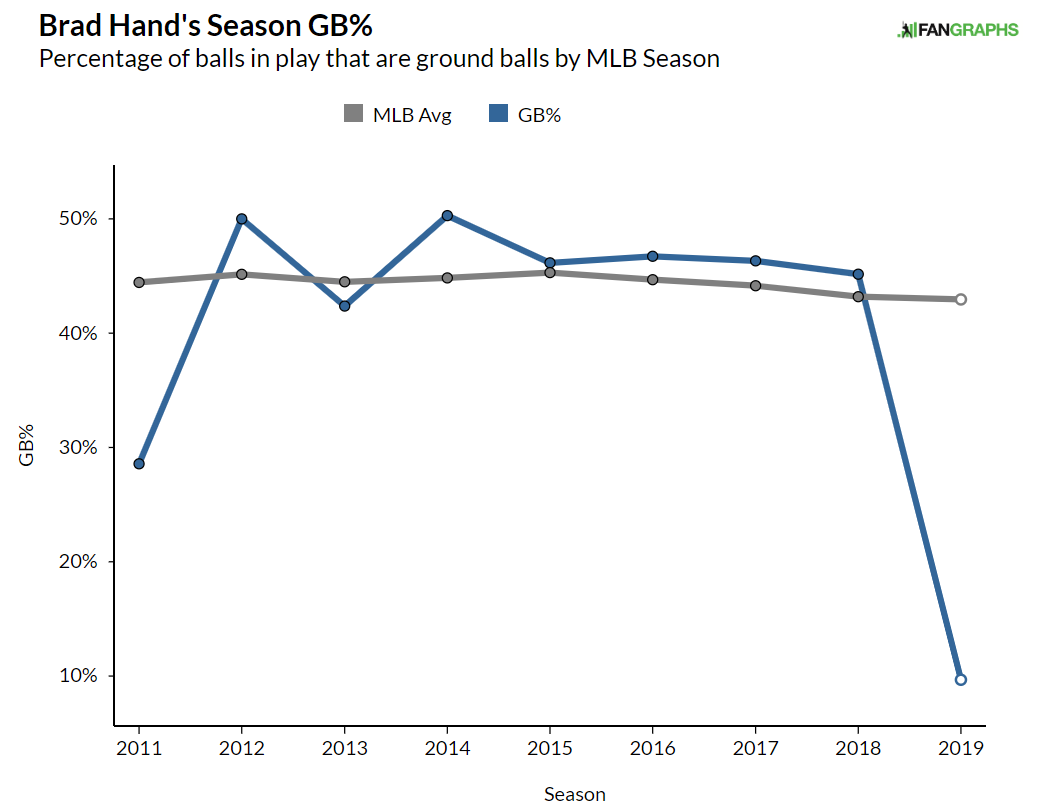

There’s nothing too surprising about a good reliever continuing to be good. Hand struck out 35% of the batters he faced last year; he’s up to 39% this year, which is better but not obscenely so. If you don’t look at Hand’s batted ball data, in fact, you might think nothing has changed. The fact that I wrote that, though, means that you should look at his batted ball data; something jumps out immediately there. Take a look at this graph of Hand’s groundball rate by year:

What the… Brad Hand has the lowest GB% in baseball this year, and it’s the lowest by a lot. His 9.7% mark is less than half the next-lowest rate. The distance between Hand and second-place Jeffrey Springs is the same as that between Springs and 23rd-place Roenis Elias. That’s quite a change for a pitcher who had run a higher-than-average groundball rate the last three years.

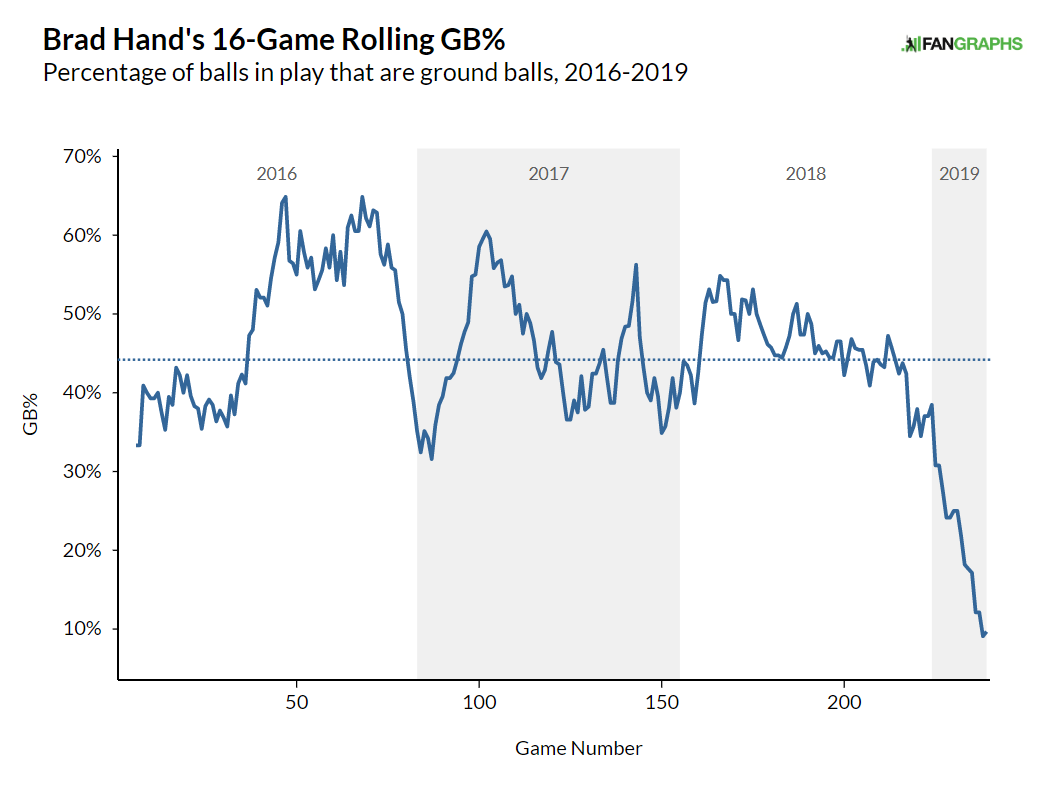

The first thing to ask when seeing a split as extreme as this is “Is it April?” Now, while it’s not April, it’s still early in the season, particularly for a reliever. Hand has appeared in 16 games this year, so let’s take a look at his groundball rate over every 16-game stretch since 2016:

Yeah, okay, something’s up.

The first thing I look for when someone’s underlying statistics change this much is a pitch usage change. Switching from a two-seam to a four-seam fastball is a good way to induce fewer groundballs, and it has the added benefit, for an analyst, of being easy to explain. Sinkers sink, four-seamers rise, my work here is done, let’s grab a drink. That, at least, is how it goes in my head. Indeed, Hand has cut back on his two-seamer this year:

| Year | FF% | FT% | SL% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 27.7 | 33.2 | 30.5 |

| 2017 | 26.9 | 24.0 | 45.0 |

| 2018 | 30.0 | 15.8 | 54.3 |

| 2019 | 49.0 | 4.1 | 46.9 |

Case closed! Wait, though. Hand barely changed 10% of his pitches from sinking to four-seam fastballs. How can that drop his groundball rate by 35%? Well, it can’t. Hand’s two-seam fastball produced 25 groundballs last year. Pro-rate that down for how many pitches Hand has thrown this year, and that would be four extra groundballs (against the zero his much-reduced two-seamer has generated). Add those “missing” groundballs back, and Hand would still be one of the least grounder-happy relievers in baseball.

In fact, the fastball mix is only part of the story. Take a look at Hand’s groundball rate, only this time, I’ve separated it out by pitch type:

| Year | FF | FT | SL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 32.8 | 60.2 | 43.5 |

| 2017 | 37.7 | 50.6 | 46.4 |

| 2018 | 28.0 | 65.8 | 47.8 |

| 2019 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 |

Sigh — looks like it’s not as simple as junking one pitch. Hand’s other two pitches are both getting fewer grounders, too. In fact, their declining groundball rate has contributed more to his fly-happy ways than his fastball usage change. Let’s handle these one by one.

First, let’s look at Hand’s four-seam fastball. Here are some relevant metrics on the pitch in 2018 and 2019:

| Year | V Movement (in) | H Movement (in) | V. Rel Point (ft) | Velo (mph) | Spin (rpm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 8.2 | -6 | 6 | 94.2 | 2476 |

| 2019 | 8.9 | -6.5 | 6.2 | 92.6 | 2405 |

Now, I’m not a physicist. I can’t describe to you exactly what Hand is doing differently to the ball. I can say with certainty, however, that he’s getting more rise and fade on his fastball this year, and he’s doing that by throwing it from a higher arm slot. Now, is he improving his spin efficiency by changing his release point? Again, not a physicist, but Hand is getting more movement out of less rpm, so that seems like a reasonable conclusion to reach.

Looking at players with similar horizontal and vertical break on their fastballs is enlightening. First, the list of pitchers who have thrown 100 four-seamers in 2019 and have more break on both axes than Hand:

| Player | V. Movement (in) | H. Movement (in) | GB% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caleb Smith | 8.98 | -8.12 | 29 |

| Hansel Robles | 9.3 | -7.26 | 27 |

| Joe Harvey | 9.32 | -7.14 | 32 |

| Thomas Pannone | 9.06 | -6.85 | 24 |

| Jeffrey Springs | 9.03 | -6.57 | 17 |

Every single one of them has a GB% lower than league average for four-seam fastballs (35%). Take a look at 2018, and it’s more of the same:

| Player | V. Movement (in) | H. Movement (in) | GB% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caleb Smith | 9.27 | -7.56 | 16 |

| Hansel Robles | 9.02 | -7.46 | 30 |

| Danny Barnes | 9.16 | -7.08 | 26 |

| James Paxton | 9.07 | -6.71 | 30 |

| Chasen Shreve | 9.87 | -6.57 | 23 |

Now, this isn’t close to anything definitive, and no one is running the crazy-low rates that Hand is. It’s reasonable to expect Hand’s fastball to generate more grounders the balance of the year than it has so far. Still, though, the new shape of his fastball (greatest vertical and second-greatest horizontal break of his career) is a shape that generally induces fly balls.

Okay, so Hand scrapped his sinking fastball and retooled his four-seam fastball to generate fewer grounders. That’s a start. Heck, for most players, that would be a solid answer. There’s still the matter of Hand’s slider, though. It’s not quite the outlier-to-end-all-outliers that his fastball is, but the drop-off in groundball rate is still extreme.

On this one, I confess that I’m stumped. Hand throws a sweeping, frisbee-action slider that generates a ton of whiffs, but it hasn’t previously demonstrated strong fly ball tendencies. Among sliders with Hand-level or higher horizontal break, we’re looking at a complete mixed bag — anything from Adam Ottavino’s 17% groundball rate to Sonny Gray’s 57%. Trying to apply a rule of thumb here is nearly impossible.

Still, there are some clues in what Hand has done to change his slider. It has more horizontal break than ever, and less vertical drop than ever. Not only that, but in a small sample this year, he’s locating it around the bottom of the zone less. We’re looking at 100-ish sliders here, so this is very much prone to change, but he’s thrown 5% fewer sliders below the zone (league 56% GB rate) and moved those off the plate wide (45% GB rate). It’s a small change, but it’s there.

As hard as it is to tease out the cause of all these fly balls, the result of them is pretty straightforward — Hand hasn’t allowed a home run all year. As you might expect from a homer-free pitcher in the year of the home run, he’s been getting a little lucky — his xwOBA allowed on fly balls, line drives, and pop-ups is .347, which is nearly a hundred points higher than his actual wOBA allowed (.255). Even then, though, that’s pretty phenomenal. League-average wOBA on balls hit in the air is .495 this year. Hitters are putting Hand’s pitches in the air, but they’re doing so without much force.

Want some specifics? Well, only two hitters have hit a ball 100 mph or harder in the air off of Hand this year — Alex Gordon and Hunter Dozier each singled off of him in the same game. The furthest a ball has traveled against him on the fly is 344 feet, so it’s not like he’s relying on the big part of the ballpark to prevent home runs. In fact, Hand hasn’t been barreled up all year (in the Statcast sense of the word).

So, this is Brad Hand right now. He tweaked his pitch mix to de-emphasize groundball pitches. He changed the way he throws his fastball, also in a way that leads to more fly balls. His slider has more run and less drop than before, which might contribute to his fly ball ways. In the midst of all of that, though, batters are making incredibly poor contact against him.

As is often the case for such an extreme outlier, predicting what comes next is a study in guesswork. Some of the groundball decline is real, intended — scrap a two-seamer and add rise to your fastball, and you’re going to get more balls in the air. Some of it is luck — his fastball probably isn’t the least likely of all time to be hit for a groundball, and he barely changed his slider.

Some of it is complex — will he keep having such tremendous success on batted balls when hitters adjust to his new pitches? He hasn’t faced any hitters more than twice yet this year, and with a re-imagined arsenal of pitches, that surely helps. One thing I can say more or less for certain is that Hand won’t end the year with a groundball rate so extreme. Aside from that, though, it’s as clear as mud. Hand is different, shockingly and effectively so, and yet it seems that he’s accomplished it through tinkering at the margins. In a strange year for baseball so far, this stands out as one of the most weirdest pitching performances to me.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

The ball is just juiced and is rising higher out of his hand.