Brady Singer Is the Last Man Standing in Kansas City

Very few things have gone according to plan in Kansas City this season. Yes, Bobby Witt Jr. made his major league debut alongside a number of other promising young position players, but the team is still on track to lose 97 games, their sixth consecutive losing season. After investing in a number of free agents prior to the 2021 season and taking a few small steps forward, the franchise has taken one giant leap backwards this year.

Their inability to break out of a rebuilding cycle that began after their 2015 World Series victory led to the dismissal of president of baseball operations Dayton Moore earlier this month. After guiding the franchise for 16 years, the Royals decided new leadership was required to push the team back into relevance. While Moore was sometimes ridiculed for his adherence to old school methods of roster construction and strategy, his track record should speak for itself. After taking the helm in 2006, he slowly rebuilt the entire organization, culminating in their championship season. Unfortunately, that success was short lived and the team slipped into another rebuilding cycle soon afterwards.

Last week, R.J. Anderson wrote about what’s next for the Royals as the franchise navigates this inflection point. He identified one glaring issue that has really sunk the team during its rebuild: an inability to draft and develop high-quality pitching. Since 2014, Kansas City has drafted 10 pitchers in the first round – two-thirds of their first round picks in that period were spent on hurlers. That’s an enviable amount of talent but thus far, almost all of it has been squandered:

| Player | Draft Year, Round, Pick | Highest Level | MLB Seasons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brandon Finnegan | 2014, 1, 17 | MLB | 2014-18 |

| Foster Griffin | 2014, 1, 28 | MLB | 2020-22 |

| Ashe Russell | 2015, 1, 21 | R | — |

| Nolan Watson | 2015, 1, 33 | AA | — |

| Brady Singer | 2018, 1, 18 | MLB | 2020-22 |

| Jackson Kowar | 2018, 1, 33 | MLB | 2021-22 |

| Daniel Lynch | 2018, 1, 34 | MLB | 2021-22 |

| Kris Bubic | 2018, 1, 40 | MLB | 2020-22 |

| Asa Lacy | 2020, 1, 4 | AA | — |

| Frank Mozzicato | 2021, 1, 7 | A | — |

A year after being drafted, Brandon Finnegan was traded to the Reds in the big Johnny Cueto swap; he has been out of the majors since 2018. Foster Griffin made his major league debut with the Royals in 2020 and was traded to the Blue Jays in July after pitching just six big league innings for Kansas City. Both Ashe Russell and Nolan Watson stalled out in the low minors, with injuries affecting the career of the former and a 6.32 career minor league ERA holding back the latter.

The 2018 draft class stands out as a particularly egregious example of unfulfilled potential. That year, the Royals drafted Brady Singer, Jackson Kowar, Daniel Lynch, and Kris Bubic in the first round. At the time, it was lauded as a draft class that could drastically change the fortunes of the franchise. Four years later, all four have made their major league debuts — an exceptional graduation rate — but just one has made a true impact in Kansas City:

| Player | Age | IP | K-BB% | ERA | FIP | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brady Singer | 25 | 340.1 | 15.7% | 3.91 | 3.84 | 5.9 |

| Jackson Kowar | 25 | 46.0 | 6.4% | 10.76 | 6.41 | -0.6 |

| Daniel Lynch | 25 | 195.0 | 10.6% | 5.22 | 4.64 | 1.3 |

| Kris Bubic | 24 | 304.0 | 9.1% | 4.97 | 5.00 | 1.0 |

Kowar has looked particularly lost in the big leagues, and both Lynch and Bubic have floundered in their limited time at the highest level. It’s still probably a little too early to call it quits on those three — particularly the latter two — but thank goodness Singer has found some success this year.

Singer made his major league debut two years after being drafted and put up some pretty solid numbers across his first two seasons in the big leagues. He posted nearly identical 4.08 and 4.04 FIPs in 2020 and ‘21, though his ERA ballooned to 4.91 last year, a result of some poor BABIP luck and an extremely low strand rate. Despite that modest success, Singer was relegated to the bullpen to start the 2022 season. He made three appearances as a long reliever before being sent down to Triple-A to reset and build back up to a starter’s workload. He was recalled on May 17 and hurled a seven inning scoreless gem against the White Sox, striking out nine, a new career-high for him. He then held the Twins scoreless over another seven innings in his next start. All told, he has compiled a fantastic 2.85 ERA and a 3.52 FIP in 23 starts since returning to the majors.

Earlier this year, The Athletic’s Eno Sarris and Alex Lewis investigated what seemed to be an organizational problem with fastball quality. They identified numerous issues with shape, location, and velocity that were present throughout the Royals pitching staff.

“Since the beginning of 2021, the Royals’ starters have the smallest vertical difference between the movement on their four-seamers and sinkers. They’re trying to throw better four-seamers but, right now, it’s hard to tell which type of fastball they’re even throwing. … Overall, it appears as if optimal mixes of location, shape, and velocity are lacking for the Royals’ starters right now. Whether it’s in the scouting department or the coaching department — or a combination — it’s clear something has to change for their fortunes to improve.”

It’s important to note that Singer was demoted to the minors just a few days after that article was published and wasn’t mentioned in it at all. That’s key because since being recalled, the shape of Singer’s sinker has improved dramatically. During his 2020 rookie season, his sinker averaged around 19.1 inches of raw vertical break. That amount of movement sits in the dreaded middle zone between a four-seamer and a sinker, close enough to both pitch types to be ineffective. A slightly higher release point last year affected the pitch’s spin axis and resulted in a pitch that didn’t drop as much. Batters jumped all over it, knocking it around to the tune of a .384 wOBA and a .385 expected wOBA on contact. The pitch did generate a few more swings and misses, but even a 22.3% whiff rate couldn’t offset all that loud contact.

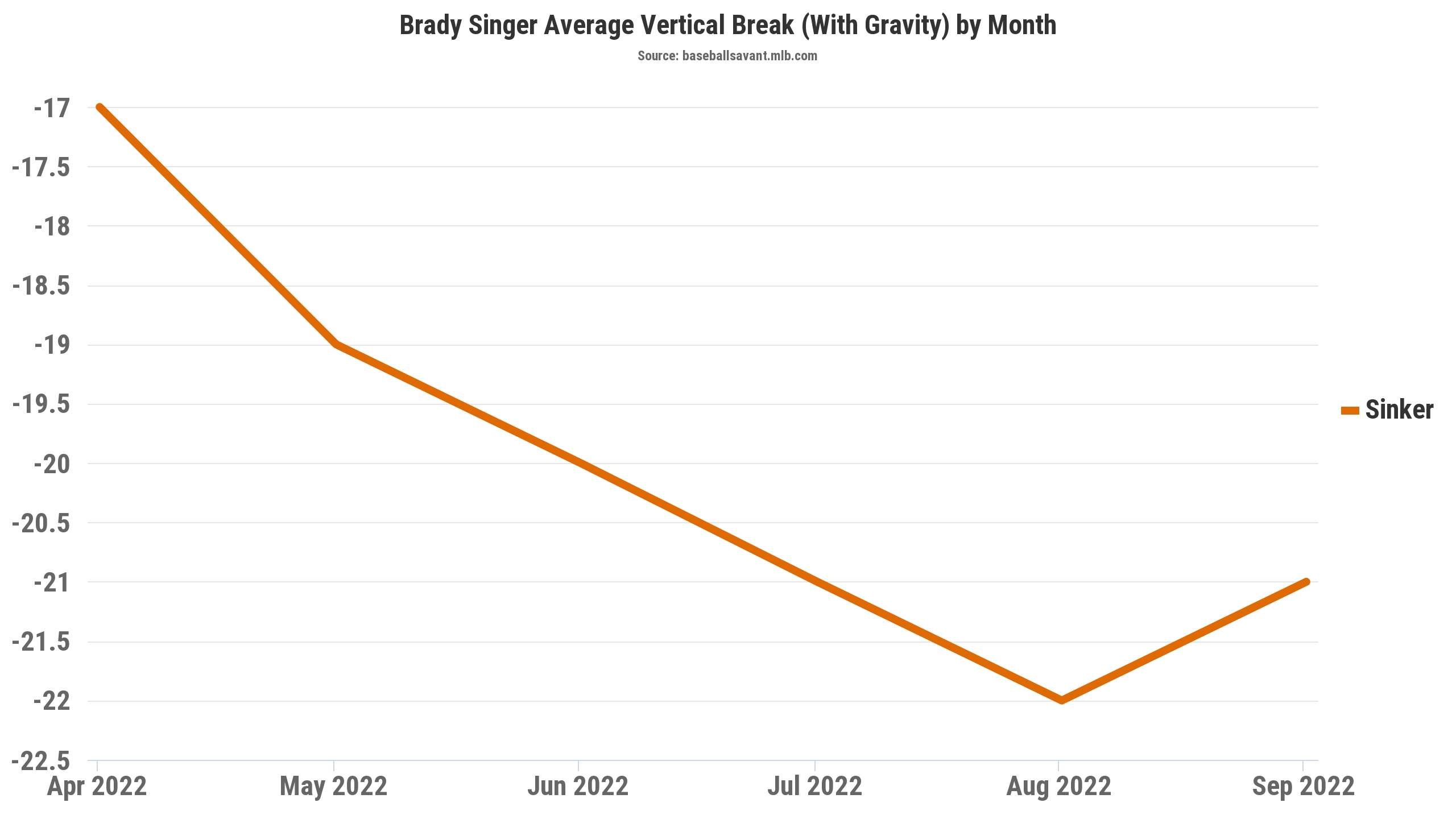

Singer’s release point has dropped this season, below where it was in 2020, and the shape of his sinker has definitely benefited:

After averaging 17.7 inches of raw vertical movement last year, he’s added three inches of drop to the pitch and has improved the shape of it each month as the season has worn on. The pitch still doesn’t stand out when compared to other sinkers around the league, but its effectiveness has definitely returned. He’s allowed a .314 wOBA and a .356 expected wOBA on contact with the pitch, both marks slightly better than league average for the pitch type. The pitch’s whiff rate has dropped to 14.1%, decent for a sinker but well below what he was generating last year.

When he needs a swing-and-miss, Singer turns to his slider. That pitch has always been a weapon for him and its whiff rate currently sits at a career-high 33.7%. The biggest difference with his breaking ball is where he’s locating it. He’s throwing his slider in the zone far more often this year (48.4% of the time, up from 44.6% last year), and despite catching more of the plate, the pitch has been as effective as ever. In the zone, opposing batters are still whiffing 19.9% of the time they swing at the pitch, the highest in-zone whiff rate of Singer’s career and well above league average for the pitch type.

It’s not just his slider either. Singer is throwing his sinker in the zone nearly 60% of the time, a huge jump from what he was doing previously. While piping sinkers over the plate might not be the most ideal approach, it has worked well for him due to the aforementioned improvements in contact management. And by locating in the zone so much more often, Singer has reduced his walk rate from 9.0% to just 5.7%. He’s reduced the number of baserunners he has to work around, which means the contact he does allow isn’t as likely to result in a run scoring. A BABIP that’s fallen back to league average and a strand rate that’s greatly improved has led to an ERA that’s outpaced his FIP by more than half a run.

If there’s one concern worth monitoring, it’s Singer’s lack of a third pitch. He’s thrown a changeup around 7.8% of the time this year, a career-high, and nearly all of them have been thrown to left-handed batters. It’s not a particularly effective pitch, but it does give him something to keep opposite handed batters in check. The other problem that comes with Singer’s shallow repertoire is a significant penalty when facing a lineup more than twice; his wOBA allowed when working through a lineup for the third time jumps up to .354. Continuing to develop his changeup could help solve those issues, but his sinker and slider provide a solid foundation that’s been working for him this year.

It’s unclear whether the Royals will look to overhaul their entire development staff when Moore’s permanent replacement is named. With plenty of raw pitching talent languishing in the organization, improving their pitching pipeline should be a top priority for whoever takes over baseball operations. Defying the downward trend of his fellow draft class, Singer has made the right adjustments and improved his outlook. He might not be a frontline starter for the next great Royals team, but he can be a solid contributor in the meantime. That’s more than can be said for the rest of the Royals staff right now.

Jake Mailhot is a contributor to FanGraphs. A long-suffering Mariners fan, he also writes about them for Lookout Landing. Follow him on BlueSky @jakemailhot.

I realize that the author starting his analysis with the 2014 draft doesn’t mean he’s unaware of the prior 8 years, but I think it’s worth pointing out that the inability to develop starting pitching is a defining theme of Dayton Moore’s tenure from 2006 to the present. The postseason rotations in 2014 & 2015 featured precisely 1 (one) homegrown starter in Yordano Ventura (RIP), an international signing. Danny Duffy is the only other clearcut success story of Moore’s first decade or so. That is a staggering degree of ineptitude. One might expect four or five league-average starters to come through any team’s system in that time, if only due to the volume of draftees/international signings and a normal distribution of luck.

As a Royals fan, I am extremely grateful for those glorious years and the flags Dayton Moore helped bring to KC. But looking back, it is hard to wrap my mind around that many years of digging for starting pitchers and finding the well nearly bone-dry.

I should add and addendum to point out that Sean Manaea became productive, but was traded before he made it to The Show and found success. Credit should go to Dayton for drafting and developing him into the cornerstone piece of an important deadline deal for Zobrist.

They also had Odorizzi as well (and Mike Montgomery) but dealt them in the trade for Shields. And some of it was also pretty bad luck with Zimmer’s arm falling off and the aforementioned Ventura tragedy.

I’m not defending the Royals pitching development because its clearly not great but its also not quite as bad as you paint either.

Yeah, I almost included Odorizzi in the addendum, but he was drafted by Milwaukee, was in their system for 3 years, then spent two minor league seasons in the Royals system, and was traded after two starts with the big league club. So maybe partial credit there.

I don’t think Montgomery got particularly close to the “league-average starter” criterion. He did put up 3 seasons between 1 and 1.5 fWAR, but he topped out at 19 Games Started in 2018 (along with 19 games in relief that year). He was a productive swing man for a few years.

It seems to further the point that the Royals pitching development stinks that we’d debate Mike Montgomery as a potential success…

It is pretty embarrassing but one thing I’ve noticed when we start looking at “homegrown pitchers” is that it becomes really hard to assign credit. If you look starting pitchers from 2017-2022 at the very top you have a lot of cases where someone was clearly developed by one org (Sale, deGrom, Burnes, McClanahan, Verlander, Bieber, Kershaw, Nola, Woodruff). But there are some where it’s harder to really pin down or where it’s not clear any team should be getting “credit” (Ohtani, Cole, Scherzer) and the moment you get down from the top tier you start getting a whole lot of guys where the credit gets complicated (Giolito, Glasnow, Darvish, Bauer, Ray, Fried, Eovaldi, Castillo, Gausman, Gallen, etc).

I think it’s pretty clear there are some teams that are legitimately good and finding and developing starting pitching. The Guardians, Brewers, Mets, and Dodgers fall into that category. The Giants and Rays historically were in this bucket too, not sure if they still are. The Mariners and Marlins look like they are maybe that kind of team now, but it’s too soon to be sure; the Astros seem like they’re especially good at developing groundball specialists like Keuchel and Framber but beyond that it’s hard to say for sure. But there are something like 12-15 teams that have records that are more like the Royals than not. Over the Dayton Moore era, how do the D-Backs, A’s, Cubs, Pirates, Rangers, Orioles, Padres, Tigers, Twins, Reds, Nationals, and Angels do in terms of obviously homegrown pitching? Not good!

I’m not sure how much credit a team might get for identifying and drafting future ML pitchers.

Some players get traded early so their original team can be credited with identifying them but it is the the latter team that actually developed them.

And then there’s the players drafted as “can’t miss” that do miss versus lower round picks who exceed all expectations. In the latter category we have a team like Cleveland that has a track record of drafting good but not imposing young college pitchers who quickly bloom into prospects: do they see something everybody else undervalues, do tbey have a “secret” program that might work on most everybody, or are they just lucky? (I suspect it’s a bit of all three but they do have something going on that lets them get more out of fifth rounders than most teams get out of first rounders.)

It may be that focusing on outliers like Cleveland and Los Angeles distorts expectations. There might be a study to be made of identifying what the “normal” success rate might be for different buckets of draftees. Then we could figure out who is good, bad, or just average.

Yeah I think the probably correct answer here is that its a little bit Royals and a lot of pitching is super hard to evaluate/develop. Very few teams are able to consistently do it.

I think the bigger issue is that the Royals need to be better and evaluating and developing players across the board. Their previous good team featured Hosmer (#3 pick in the draft), Gordon (#2 pick in the draft), and Moustakas (#2 pick in the draft), coupled with two roughly ready-made guys they got from the Brewers in the Greinke trade.

There are a lot of high draft picks that bust so they do deserve some credit. But when almost all of your success on the position player side comes from only 5 guys who have 650+ PAs a year and all of them were consensus top guys or already developed by other teams you do not have a robust development system on the position player side. It’s better than the pitching development but it’s not that great either.

I think the only guys who were net positive contributors who don’t fit that definition from 2012-2017 were Salvador Perez, Jarrod Dyson, Billy Butler, and Whit Merrifield.

In any case, once you couple the position player development with the pitching development, you start to see that this is just something they need to get better at across the board.

Yeah, it does become difficult to assign credit, especially when players are traded while in the minors. Just looking at your first example, the Diamondbacks have some successes, to varying degrees, from the drafts after 2006 with guys like Bauer, Miley, Anderson, and Collmenter. My bar is low here — I’m looking at guys who put up more than 1.5 bWAR as a starter in multiple seasons — but that’s the bar I used for the Royals, also. (I’m using a b-ref because it’s easier for me to navigate for this sort of thing.) Then the D-Backs have 2 guys they traded for one year after they were drafted by other teams: Corbin and Godley. So some degree of partial credit for them, and probably more than KC deserves for Odorizzi. Of course, as you alluded to, they traded Bauer after 4 starts. He was excellent in the upper minors that year, so they at least drafted him and didn’t screw him up before trading him in what would become a terrible move in hindsight, at least w/r/t on-the-field impact.

I don’t have the interest in going through all the teams you listed, but I find it hard to imagine more than a handful of teams got fewer league-average starters from the draft/intl. signings from 2006 to present than the Royals.

I think there’s some truth in what you said below about offensive player development being an issue, too. I just think that failure pales in comparison to the pitching in the Dayton Moore era. Developing starters is hard — TINSTAAPP and all that — but I think the thesis that Moore’s Royals were among the worst in baseball at this (highly difficult!) task is essentially correct.