Brandon Workman Won’t Let You Beat Him

Last Saturday, Boston Red Sox right-hander Brandon Workman authored an outing that was fairly representative of his 2019 season. He entered the game in the ninth inning, with the Red Sox ahead of the host San Diego Padres by a score of 5-4. At just 6.4% playoff odds according to our own calculations, Boston remained in the American League playoff hunt only on the periphery, but even that could take a significant blow with a loss in a game like this. Workman’s job, then, was an important one.

He began the inning with three straight curveballs to Austin Allen. The first one was called a strike, while the next two eluded Allen’s swinging bat:

He attacked the next hitter, Ty France, in a similar fashion. He threw three straight curveballs, but instead of throwing them at the knees, he aimed them up in the zone. All three missed their target high, and another high fastball gave France a free base. Next up was Josh Naylor, who saw seven curveballs in a row. The first was taken for a strike, followed by three balls and two foul balls. The final pitch of the at-bat froze Naylor in place for the second out:

Next came Manny Machado, who saw five pitches, four of which missed outside, resulting in Workman’s second walk of the inning. That set up the tying run at second and winning run at first for Eric Hosmer, who fouled off a cutter and a four-seam fastball in on the hands to fall behind 0-2. The next pitch was impossible:

Workman isn’t the pitcher who Boston expected to be relying upon to close games this season, but there’s a good reason he has that responsibility now: He’s been incredibly difficult to hit. In 59 innings out of the bullpen, Workman has allowed just 24 hits, just one of which was a homer. He’s walked a lot of batters (35) but he’s also struck out 85. Those numbers have culminated in a 1.98 ERA, a 2.38 FIP, and 1.7 WAR for the 31-year-old this year. In a Red Sox bullpen that has been among baseball’s best — ninth in ERA, fourth in FIP — Workman has probably been the best of the bunch.

Those are surprising results from someone who pitched in the minors for half of each of the previous two seasons. Workman, Boston’s second round pick in 2010, broke into the big leagues for the first time in 2013, and pitched back-to-back partial seasons in which his ERA (5.11) looked much uglier than his FIP (4.12). Before he got a chance to close that gap in 2015, though, he was sidelined with an elbow strain in the spring, and eventually underwent Tommy John surgery in June. That caused Workman to go two full seasons without an appearance in the majors. He did well when he returned in 2017 (3.18 ERA, 4.49 FIP), and after spending the first two months of 2018 in the minors, continued to produce solid numbers (3.27 ERA, 4.49 FIP) in the team’s championship season.

This season, however, his performance has taken off, and it’s because he’s been a different pitcher. The first three seasons Workman pitched in the majors, he used over half his offerings on a low-90s fastball, and split the other half of his pitches between a cutter and a curveball. Two years later, his four-seamer and his curveball have completely switched places.

Workman throws his curveball with about 47% of his pitches. Just two relievers in baseball have thrown curves as a greater percentage of their offerings, one of whom is his teammate Matt Barnes. No one, however, has gotten better results. According to our pitch weights, Workman has a wCB of 11.5 this season, the best mark out of all relievers in baseball. In 134 plate appearances ending with the curve, hitters are hitting just .130/.246/.200 with 47 strikeouts against Workman, good for just a 37 wRC+. The batted ball data is no kinder to hitters — the curve has generated a .190 xBA, and a .267 xSLG. It’s a dominant pitch, and Workman uses it with abandon.

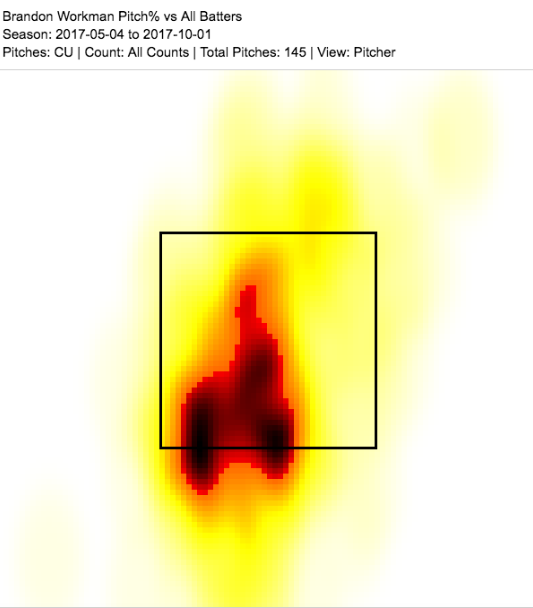

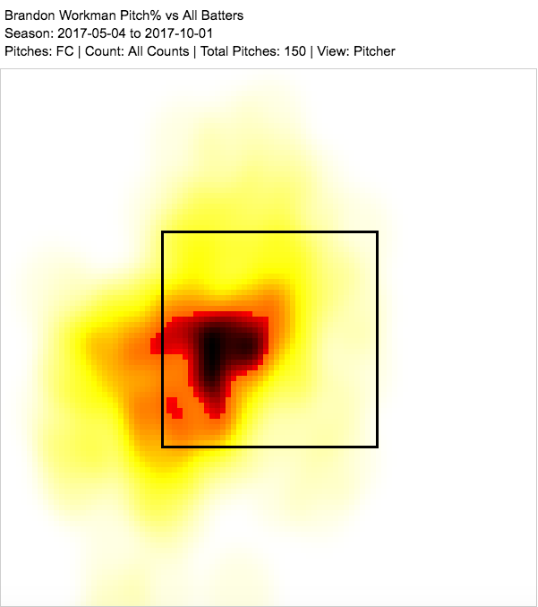

The secret to the curve’s success has been its location. The pitch itself is a good one, with 5.1 more inches of vertical drop than average and a spin rate that ranks in the 66th percentile. But it had similar spin and drop in 2017, when opposing hitters recorded a 140 wRC+ against it. The difference is comes in where Workman has thrown it. Here’s where he threw the curve in 2017:

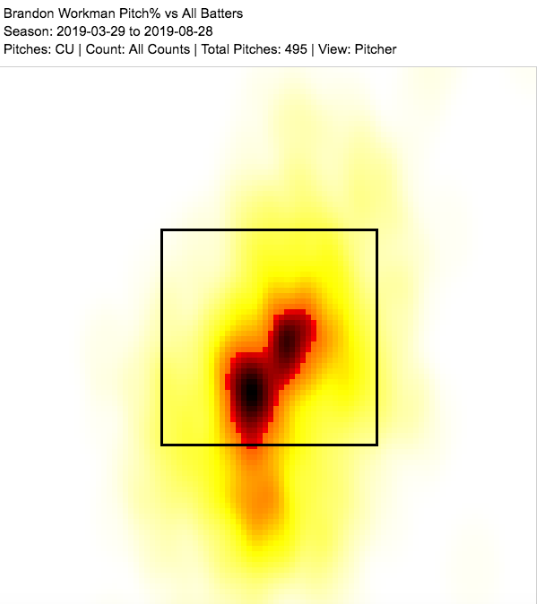

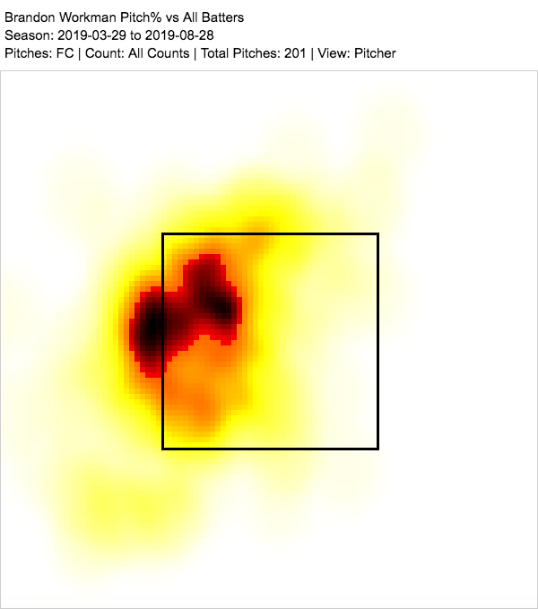

And here’s where he’s located it this season:

He’s still throwing the curveball over the middle of the plate some, but he’s doing so with less frequency than he used to. Meanwhile, he’s throwing a ton of curveballs over the middle and below the knees, allowing the 12-6 motion of the pitch to start off looking like a meatball and finish out of the batter’s reach.

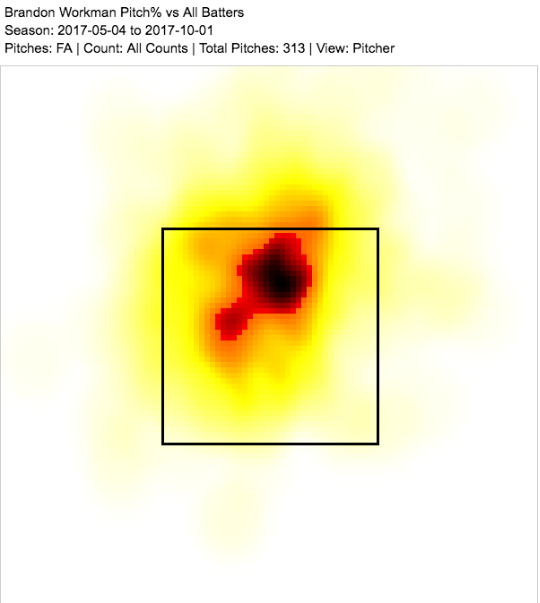

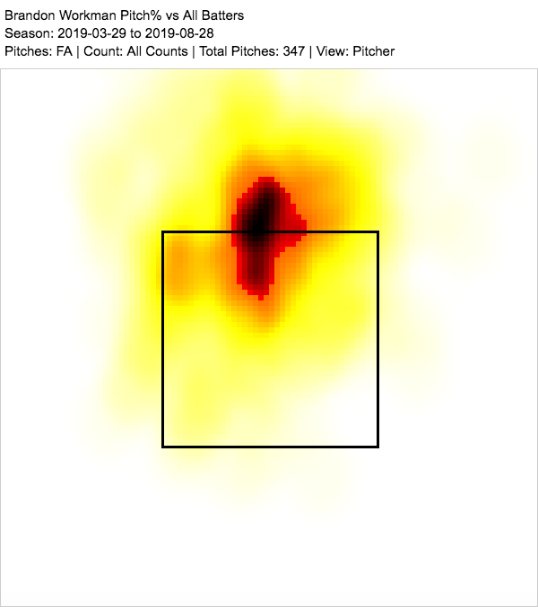

Workman hasn’t become dominant with just one overpowering pitch, though. He’s done it with three overpowering pitches. While opposing hitters are producing a wOBA of .212 against his curveball, they have just a .177 wOBA against his four-seamer, and his cutter has generated an opponent’s wOBA of .242. Those results are indicative of truly unhittable pitches, but that doesn’t necessarily describe Workman’s harder stuff. His fastball velocity and spin are quite mediocre, with both ranking in the bottom 25% of baseball. But like he does with the curveball, Workman simply throws hard stuff where hitters can’t reach it.

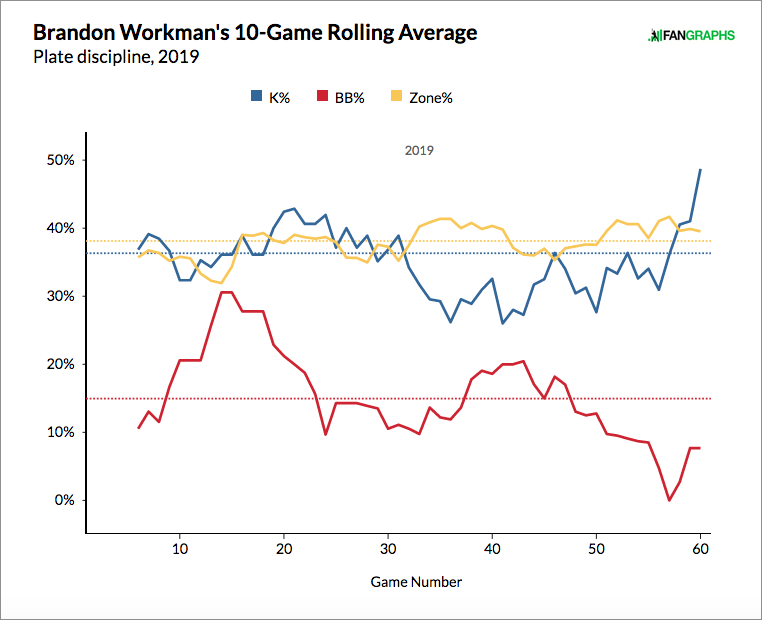

With all of his pitches, Workman has simply been unafraid to force hitters to chase him out of the zone. After throwing 44.9% of his pitches in the strike zone last season, he’s thrown just 38.1% of his pitches in the zone this year. Despite that change, hitters are swinging at about the same number of pitches they did a year ago, with the overall swing rate falling just 1.2%. That’s because Workman has converted a shocking number of his zone swings into chases — his zone swing rate is down 7.3%, while his chase rate is up 7.6%. Unsurprisingly, those swings are missing more than ever, with his 68% contact rate down nearly seven points from a year ago.

One would think this shouldn’t be sustainable. If a pitcher is throwing out of the strike zone this often without elite velocity, it seems like hitters should be able to simply begin waiting him out, refusing to give in to the neck-high fastball or the tempting curve. The way this season has been going for Workman, however, the opposite seems true. Throughout the year, Workman’s zone percentage has remained consistently low. But after 60 games, his walk rate has recently hit its lowest point of the year, while his strikeout rate is higher than ever.

The minuscule hit rate against Workman seems sustainable, too. His .205 BABIP — the fourth-lowest mark of all relievers — is bound to come up some, but not necessarily to a problematic degree. His xBA is in the 98th percentile in all of baseball, and his xSLG is in the 100th percentile. According to Statcast, out of 113 batted balls against Workman this season, just one was a barrel. He consistently generates bad contact, because he’s almost never offering good pitches to hit. His new repertoire has turned him from a fringe bullpen arm into a legitimately dominant late inning guy. If you’re a batter facing Workman, and you’re patient enough, you might be able to work a walk against him. But you’re probably not beating him with a hit. He just won’t give you the chance.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

So who was the one guy to barrel him up and when did it happen?

Charlie Blackmon, May 14. It was Workman’s only HR allowed so far.

https://baseballsavant.mlb.com/sporty-videos?playId=aff1a3b1-4aae-4370-acf2-3a85cadb028e

And that still wasn’t a bad pitch! Impressive hitting.