Brian McCann’s Great Career and Fascinating Hall of Fame Case

Atlanta’s Game 5 loss to St. Louis last week marked not only the end of a season, but also the end of an era, as Braves catcher Brian McCann announced his retirement after the contest. It came without much warning: McCann hadn’t tipped his hand publicly and he certainly could have found work in 2020 had he wanted to play. For a man who mostly kept quiet away from the diamond, his understated goodbye was a fitting conclusion to a great and perhaps under-appreciated career. While at times overshadowed by others at the position, McCann was one of the game’s premier catchers for more than a decade. His steady production at the plate and prowess with the glove made him a star — and an intriguing test case for Cooperstown.

McCann was Atlanta’s second-round pick out of Duluth High School in Georgia in 2002, a prequel of sorts to the club’s strategy of locking down home-state talent in the draft later that decade. High school backstops are a notoriously risky player pool, but McCann bucked the odds and blossomed into one of Atlanta’s top prospects almost immediately. He was one of the best players in the Sally League as a 19-year-old, and he slugged nearly .500 in the pitcher-friendly Florida State League a year later. He then proved equal to the Double-A test in 2005. Fifty games into the season, he’d walked nearly as often as he’d struck out and with good power to boot. Stuck in third place and receiving little production from their catchers, Atlanta summoned him to the big leagues that June. (The minor league skipper who delivered the good news? None other than Brian Snitker.)

McCann made his debut at 21 years old and homered in his second game. True to form, he circled the bases quickly and unemotively, not even cracking a smile until he’d reached the dugout. By mid-August, he’d claimed the starter’s job. He finished his first campaign with a respectable .279/.345/.400 line (93 wRC+) and clubbed two more home runs in the NLDS that fall. His quick success prompted the Braves to anoint him their catcher of the future and dispatch Johnny Estrada, an All-Star the previous year, to Arizona for bullpen help.

McCann immediately rewarded Atlanta’s show of faith. In 130 games, he hit .333/.338/.572 (142 wRC+) and led all National League catchers with 4.3 WAR. That kicked off a 12-year run in which he was one of the league’s best-hitting backstops. Over that span, he made seven All-Star teams and won six Silver Slugger Awards. We didn’t realize it at the time, but McCann was legitimately one of the best and most consistent players in baseball at his peak:

| Year | BA | OBP | Slugging | wRC+ | DRS | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | .301 | .373 | .523 | 135 | 47.1 | 8.6 |

| 2009 | .281 | .349 | .486 | 119 | 36.9 | 6.3 |

| 2010 | .269 | .375 | .453 | 123 | 38.0 | 6.7 |

| 2011 | .270 | .351 | .466 | 122 | 40.3 | 6.9 |

Why didn’t we realize it? If you look closely at McCann’s defensive statistics, you’ll notice that his production behind the plate jumps dramatically starting in 2008, the first year in which we have detailed framing metrics. A good blocker with a serviceable arm, McCann was always considered a decent defender, particularly given his beefy frame and lack of speed. Rudimentary catching statistics confirmed as much, but it was the emergence of reliable framing data that solidified just how valuable he was behind the plate — information that we didn’t have until earlier this decade.

Retroactively, we learned that he led all of baseball in framing runs saved in 2008 and 2009, and he remained among the league leaders well into his career. By our metrics, he’s the third-best defensive catcher over the last 12 years and the second-best framer — just a fraction behind Russell Martin, and better on a per inning basis.

| Name | Framing Runs Saved |

|---|---|

| Russell Martin | 165.7 |

| Brian McCann | 165.6 |

| Yadier Molina | 146.3 |

| Jose Molina | 143.5 |

| Yasmani Grandal | 134.1 |

On both sides of the ball, McCann’s production dipped after he left Atlanta. He signed with the Yankees in 2014, and between New York’s small right field and the increased prevalence of the shift, his batting average plummeted.

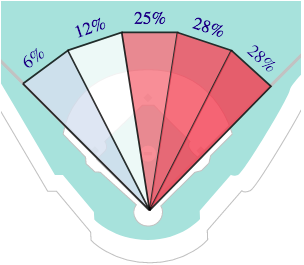

(Image courtesy of Baseball Savant)

A .300 hitter early in his career, McCann never reached .250 after leaving the Braves, and his BABIP never crested .270 after the 2011 season. He still walked plenty and hit for enough power to remain a good hitter through 2017, if not a noticeably diminished one.

The inevitable wear and tear catchers accumulate over time also contributed to his decline. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who either fully or partially moved out from behind the plate to save their legs or keep their bats fresh, McCann spent virtually his entire career in the bucket. Across 15 years and nearly 1,800 games, McCann only started 69 anywhere besides catcher. That he remained an above-average hitter through the age of 33 is notable, particularly as offense at the position atrophied throughout the league.

In 2017, McCann finally earned the ring he’d chased for 13 years. He’d been traded to the Astros prior to the season, and despite missing more than 50 games with injuries, he chipped in 2.6 WAR and a 103 wRC+ for the American League’s best team. He didn’t hit particularly well in October, though he did play an important role in Game 5 of the World Series. His solo homer in the eighth provided a crucial insurance tally, as Los Angeles would rally for three runs in the ninth to tie the game. With two outs in the 10th, Kenley Jansen hit McCann; that too proved important, as pinch runner Derek Fisher lumbered home with the game’s winning run two batters later.

After another injury-plagued year in Houston, McCann returned to Atlanta in 2019. He offered reliable defense and an adequate bat in what amounted to a job-share with Tyler Flowers. McCann emerged as the first-stringer down the stretch, and he started all five of Atlanta’s Division Series games. He played nine innings of Atlanta’s Game 5 clunker, singling in his penultimate at-bat before Snitker lifted him for a pinch-hitter in the ninth to close out his career.

Inevitably, some fans will remember McCann as a curmudgeon, thanks to a few incidents late in the 2013 season. That September 11th, José Fernández ripped his first career homer and, as he was known to do, celebrated the accomplishment. Atlanta’s third basemen, Chris Johnson, jawed at Fernández a little, but it was McCann’s yelling that sparked a benches-clearing confrontation.

His behavior was even more pronounced two weeks later. Carlos Gómez belted a first-inning homer and gave his bat a dramatic flip before he strolled out of the box. After plenty of chatter between Gómez and the Braves on his home run trot, McCann blocked his path to the plate and started a screaming match as Gómez approached; this too emptied the benches.

Reaction from the baseball world was mixed and broke down along the lines you’d expect. Many of the Braves were undoubtedly annoyed at Gómez, who had started yelling at pitcher Paul Maholm as soon as he left the box, and McCann earned kudos for sticking up for his pitcher. On the internet, McCann became a laughingstock, appearing in a number of memes and articles that lampooned his brand of hostile sensitivity. In neither incident was McCann the first to chirp at his opponent, but in each case his demonstrative yelling made him a focal point of any subsequent discussion. Fairly or not, in some quarters McCann’s angry scowl became the face of the conservatives in baseball’s Culture Wars, the embodiment of a group of staid, tradition-minded, mostly white players seeking to police a more expressive group of their mostly brown contemporaries.

But yesterday’s storm has a way of becoming today’s water under the bridge, and the image of McCann as baseball’s fun cop faded. It helped that he reportedly cleared the air with both Fernández and Gómez: He notably exchanged a hug and shared a few nice words about the latter, and he was reportedly near tears upon learning of the former’s passing. Over time, his veteran leadership and steady clubhouse presence took on more resonance than those heated confrontations. In a postgame interview last week, Dansby Swanson called him one of the best teammates he’s ever had, a sentiment echoed by a number of other Braves past and present, including Chipper Jones.

Might McCann’s career be worthy of induction to the Hall of Fame? That’s a question best answered in detail at another time. Jay Jaffe looked more closely at McCann (and Martin) back in April, and JAWS will have much more to say on the subject five years from now.

At the moment though, McCann’s record presents a novel test for the BBWAA. By conventional metrics, McCann looks ticketed for the Hall of Very Good. His raw numbers, while impressive, are well shy of the Gary Carters and Carlton Fisks of the world. He didn’t quite reach 300 homers, his wRC+ slipped to 110 by the end of his career, and you can reasonably argue that his peak wasn’t long enough to justify the first two parts of this sentence. Per Baseball Reference, which doesn’t credit catchers for their framing contributions, he accrued 31.8 bWAR — well short of the typical standard for the position.

The framing has to count for something, though. As an elite defender at a time when many teams were content to let seemingly anyone flop around behind the dish, McCann’s steady hand and nimble glovework stole hundreds of strikes and dozens of runs from his opponents. If anything, our metrics likely sell his contributions short, as they only date back to 2008. It stands to reason that McCann was probably an adept framer in the first 2 1/2 years of his career as well.

On the other hand, you could argue that McCann’s enormous framing numbers are as much the product of mediocre peers as his own considerable skill. The delta in framing production from the best to the worst catcher is much smaller these days than in an era when teams didn’t know how to properly weigh that particular contribution. It’s fair to wonder whether McCann should get full credit for winning a race that few others entered.

Regardless of how the writers interpret that slice of his career, his defensive performance should be enough to merit serious Hall of Fame consideration. How the BBWAA chooses to evaluate framing will be an intriguing subplot in an exercise that has become somewhat rote in recent years, particularly since McCann’s case will have repercussions for guys like Molina and Martin.

Whether he makes it or not, McCann’s accomplishments are worthy of celebration. He had a a long stint with the hometown nine and he leaves with a ring, 54.5 WAR, several awards and accolades, a healthy chunk of change, and hopefully a long life ahead. It would be hard to want much else.

Fine player, not necessarily of HOF caliber, and there’s no shame in that. Nice article.