Every Playoff Home Run Tells a Story, Especially the First One

Getting dropped into a single elimination Wild Card game is like kicking off the postseason with Game Seven of the World Series. Suddenly, everything is on the line. The water is boiling. Alarms are going off. Stephen Strasburg is pitching in relief. There’s always two strikes. The crowd is either deathly silent or ripping off their jerseys.

Often, these games are won with abrupt offense, and in 2019, that means home runs. The league just hit a(nother) record-breaking number of them during the regular season, so last night, the Brewers and Nationals knew it was their jobs to swat as many balls out of the ballpark as they could before time ran out.

Yasmani Grandal hit one on the first pitch he saw, gifting Milwaukee an early lead by punching an inside fastball into the Nationals’ bullpen and celebrating with a seismic slap of his first base coach’s hand.

Eric Thames clubbed the next one on Max Scherzer’s 20th pitch of the evening, a low and away shapeshifter on the corner, and they both turned and watched it sail two or three rows back in right center to make it 3-0. Thames jogged muscularly around the bases, his arm adorned with robot armor from the future.

Trea Turner hit the last one, which gave a spike to the Washington pulse; a 98 mph heater high in the zone, just where he likes ‘em — a spot where, during the regular season, he hit .625. Turner’s bomb (in theory) set off the emergency alert system at Nationals Park, as if to assure people: Don’t worry, we’re still here.

Every home run tells a story: The at-bat that preceded it. The situation that led up to it. The way the batter circles the bases. Who’s waiting for him at home when he gets there. There was once a time when the story of each home run was more memorable, as they didn’t happen very often. Three home runs in a single game would have raised suspicion of some sort of curse or sinister plot by a foreign power. That time was 1903, and it brought us the first postseason home run of all time, as well as the story that came with it.

Outfielder Jimmy Sebring’s first job that season was to convince the people watching that the Pirates’ new acquisition, pitcher Bucky Veil, was quite the acquisition indeed. It was Sebring reporters and fans turned to for confirmation of the young hurler’s skill, as the two had played at Bucknell together, giving him a close-up view on whether or not Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss’ deal would be a success or failure.

Sebring’s next job, in December 1902, was to work through the death of his father. This, as you might have guessed, was much tougher.

There might have been quite the weight around the 20-year-old’s neck when he showed up for spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas in 1903—with Veil in tow, of course. The two had done some light workouts that summer and people couldn’t wait to hear about them. It was 1903, so instead of dozens of guys rolling into camp, it was a more intimate affair, with The Pittsburg Press publishing a column of brief notes on each Pirate to allow fans to reconnect with their favorite players. It read very much like a holiday letter written by a doting parent: Tommy Leach was quiet, but working hard. Kitty Bransfield was fat now. “Roaring Bill” Brickyard Kennedy was “practicing like a two-year-old.”

Sebring’s name was listed at the top. Said the paper, Sebring “is the admiration of the Hot Springs fans. This boy will surprise the loyal rooters at home by his fine work.”

Expectations were high for the kid, and he kept them that way with a keen hitter’s eye at the plate that spring, having sharpened his instincts by playing ping-pong over the winter, he claimed. On the day he turned 21, Sebring made three plays in the outfield with the sun in his eyes and smacked three hits. Everything was coming up Sebring, it seemed, until a little over a week later, when, per Andy Dabilis and Nick Tsiotos in The 1903 World Series: The Boston Americans, the Pittsburg Pirates, and the “First Championship of the United States” a “monster centipede” bit him as he was bathing.

After an impressive pre-season, and with the toxins of an Arkansas centipede surging through his veins, Sebring would be leaned on to produce, but nobody was expecting a startling display of power from him in 1903, largely because startling displays of power did not occur often. He’d been a teenager not too long ago, and hitting home runs was men’s work, with their big burly arms and bodies fueled by 1900s cornmeal. And if home runs weren’t that, then they were the product of a successfully executed superstition; something you did because the gods had smiled upon you that morning, or because you had rubbed a rutabaga from your old family farm on your bat.

We don’t need a deep statistical dive to glean that there were more home runs across baseball in 2019 than there were in 1903. But let’s put the numbers next to each other anyway just for fun.

| 1903 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| League Total | 335 | 6776 |

| Team Average | 21 | 226 |

| Most | Boston (48) | Minnesota (307) |

| Least | St. Louis (8) | Miami (146) |

| Worst team HR/9 | Washington (0.3) | Baltimore (1.9) |

And so nobody got a startling display of power from Sebring in 1903: His four home runs and .107 ISO on the season were fifth and seventh on his own team, respectively. In fact, he wasn’t too big of an offensive threat in general, with a 99 wRC+ and 2.3 WAR. But the Pirates made the World Series that year anyway, which was distinct at the time from the 2019 version in many ways, not the least of which being they didn’t have to play in a Wild Card game to get to it, it wasn’t so much a league-mandated event and more of a handshake agreement between the owners of the Pirates and the Boston Americans, and it was the first series of its kind.

The 2019 postseason has three home runs after one game, but soon, as more games are played, there will just be a whirring blender of bats sending shredded baseballs into the night. It will be hard to parse one from the other, and at the end of it all, we’ll sit back, look at the total from the postseason, and say, “Dang.” Then, MLB’s top investigators can announce that somebody had just been standing on the anti-gravity switch at the baseball factory this whole time, and maybe things will go back to normal, whatever that was.

But when you have fewer home runs, as there were 116 years ago, it makes each of them more memorable—not necessarily better, just easier to recall. Each one has more of a personality. And Sebring’s World Series dinger, the first one ever hit, had a narrative tailing from it a mile long.

Cheating at the time wasn’t as complicated as mistaking a bottle of illegal horse stimulant for a fever reducer. You could just let a fly ball drop in front of you instead of catching it, and some nearby sleaze would hand you a stack of cash. So it became immediately suspicious when Jimmy Sebring, the youngest hitter on both teams, made contact in the top of the seventh and everything that happened… happened.

Sebring knocked Cy Young’s pitch over second base, where it hung in the air long enough to get out of reach. Buck Freeman and Chick Stahl were playing in the outfield and their lackadaisical pace was noted by some of those watching as they pursued Sebring’s hit. By the same they had recovered it, Sebring had been around the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

As Dabilis and Tsiotos note in their account:

“The smell of a fix was ripe in the air. Freeman’s insouciance puzzled everyone. And it looked like Dreyfuss, Clarke, and Leach might be right; the upstart American Leaguers might be the champions of their league, but they couldn’t stay on the same field with the National Leaguers.”

It was an incredible day at the plate for Sebring, who already had two hits and three RBI on the day, including a first-inning single that had scored two runs on what was now an even more suspect error on the Americans. But if there had been a schemer’s ploy in the works, it wasn’t a very good one; 12 days later, the Americans wound up winning the World Series in eight games anyway.

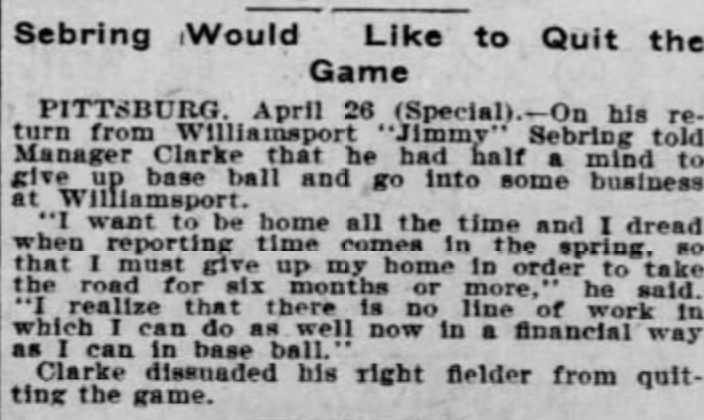

And what became of young Jimmy Sebring? Did his gleeful sprint around the diamond before the Americans could recover the ball spark a lifelong passion for baseball? Per the Philadelphia Inquirer:

No it did not.

So let this be a lesson: You don’t have to hit the ball a mile to score a run that counts. You can rely on slow-moving outfielders or the hitting prowess of a 20-year-old, as the Nationals did in the NL Wild Card game.

Tuesday night, after a brief barrage of long-distance offense, it was Juan Soto’s bases-loaded single and Trent Grisham’s raucous brain fart that sent the Nationals onward into the postseason. That isn’t a home run. But it is a pretty good story in and of itself.

Justin has contributed to FanGraphs and is a contributor to Baseball Prospectus. He is known in his family for jamming free hot dogs in his pockets during an off-season tour of Veterans Stadium and eating them on the car ride home.