Gary Sánchez Takes a Knee

While it was understandably overshadowed by Gerrit Cole’s pinstriped premiere, Gary Sánchez made his Grapefruit League debut on Monday. In doing so, he showed off a new stance behind the plate, one that’s intended to shore up the defensive inconsistencies that have cut into his value while making him the brunt of so much criticism during his tenure with the Yankees.

The game wasn’t televised, and the only video I could find was rather rough, shot from the press box and thus showing the catcher’s back, but here you can see what’s going on:

Sánchez now sets up in his crouch with his right knee on the ground, a stance whose purpose the New York Post’s George King III explained succinctly earlier this month:

The lower setup is designed to improve Sánchez’s ability to frame borderline pitches in the bottom of the strike zone but not interfere with his improved blocking skills or take anything away from an above-average throwing arm. It also may reduce the stress on Sánchez’s legs, which have suffered muscle injuries the past two seasons that landed him on the injured list a combined four times.

Wednesday’s game against the Nationals, which was televised, offered a much better view of the 27-year-old backstop’s new style:

Sánchez’s new stance is the brainchild of Tanner Swanson, a catching coordinator who’s in his first year with the Yankees after spending the two previous seasons in the Twins’ organization. Via our pitch framing metrics, Minnesota was nearly nine runs better than the Yankees in the pitch framing department last year (+3.4 runs versus -5.3), with Sánchez (-6.8) considerably worse than either catcher in the Twins’ tandem, namely Jason Castro (+3.2) and Mitch Garver (+0.8) — the later of whom improved by a full 10 runs relative to 2018. Via Baseball Prospectus‘ more elaborate catching metrics, the Twins were over 15 runs better than the Yankees (+10.0 runs versus -5.4) in framing, with the former ranking 11th in the majors and the latter 19th. Castro (+6.1) and Garver (+4.2, up from -8.2 in 2019) were again both much better than Sánchez (-5.1).

Garver spent the winter of 2017-18 working with Swanson, adopted a one-knee stance, and things clicked. Upon being named the team’s most improved player after last season, he credited the coordinator, telling The Athletic’s Dan Hayes, “I had to be a suitable defender and without the help that Tanner gave me I don’t think I would have put myself into position to really be a true option for a starting catcher. I needed to improve on a lot of things and he helped me do that.”

Though he didn’t break in until the final third of the 2016 season and ranks just 22nd in innings caught over the past four seasons, Sánchez has been charged with more passed balls (47) than any other catcher in that span. He led the AL in passed balls in both 2017 (16) and ’18 (18), the latter while catching just 76 games, though he cut his total to seven in 90 games last year.

Keep in mind that the passed ball/wild pitch distinction can be a blurry one, and that like any official scorer’s decision, a player’s reputation can be a factor in those judgment calls. Sánchez’s batterymates have thrown the sixth-highest total of wild pitches (143) on his watch, and so his rate of missed pitches — passed balls plus wild pitches per nine innings — is among the majors’ highest. Here are the best and worst catchers in that area over the 2016-19 span, prorated to 800 innings:

| Rk | Catcher | Innings | PB | WP | MP/800 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61 | Josh Phegley | 1665.2 | 32 | 91 | 59.1 |

| 60 | Omar Narvaez | 2386.1 | 22 | 153 | 58.7 |

| 59 | Gary Sánchez | 2592.2 | 47 | 143 | 58.6 |

| 58 | Jonathan Lucroy | 3746.1 | 31 | 212 | 51.9 |

| 57 | Rene Rivera | 1283.0 | 12 | 71 | 51.8 |

| 56 | Tyler Flowers | 2727.0 | 40 | 134 | 51.0 |

| 55 | Welington Castillo | 2427.2 | 29 | 125 | 50.7 |

| 54 | Elias Diaz | 1672.1 | 11 | 95 | 50.7 |

| 53 | Andrew Knapp | 1138.1 | 12 | 59 | 49.9 |

| 52 | Jorge Alfaro | 2116.1 | 25 | 107 | 49.9 |

| MLB Average | 40.2 | ||||

| 10 | Manny Pina | 1998.0 | 8 | 65 | 29.2 |

| 9 | Tucker Barnhart | 3622.0 | 18 | 114 | 29.2 |

| 8 | Carson Kelly | 1083.2 | 4 | 35 | 28.8 |

| 7 | Matt Wieters | 2930.0 | 10 | 89 | 27.0 |

| 6 | Roberto Perez | 2502.2 | 11 | 73 | 26.9 |

| 5 | Robinson Chirinos | 2949.1 | 16 | 73 | 24.1 |

| 4 | Bobby Wilson | 1138.1 | 7 | 27 | 23.9 |

| 3 | Kevin Plawecki | 1580.1 | 4 | 42 | 23.3 |

| 2 | Austin Barnes | 1447.2 | 6 | 36 | 23.2 |

| 1 | Buster Posey | 3501.2 | 7 | 93 | 22.8 |

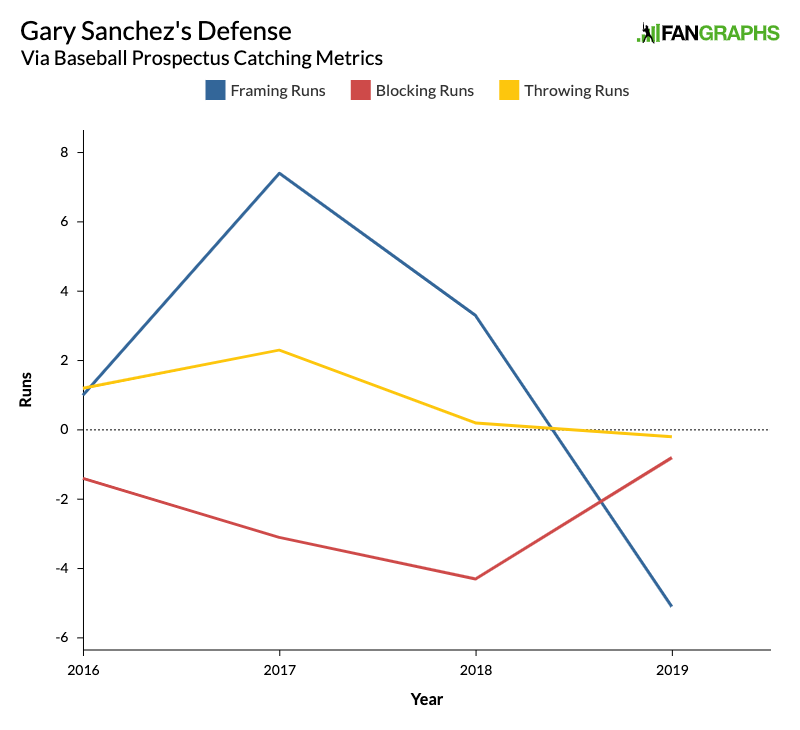

Sánchez’s rate of missed pitches over that span was 46% above the major league average, though last year’s rate (39.9 per 800 innings) was just 1% above average. Baseball Prospectus‘ metrics confirm his improvement in blocking; he went from 3.1 runs below average in 2017 and 4.3 below in ’18 to just 0.8 below in ’19. However, that improvement was offset by measurable declines in other areas:

Ever since putting Jorge Posada out to pasture following the 2010 season, Cashman and the Yankees have been ahead of the pitch-framing curve. Russell Martin, the team’s regular catcher in 2011-12, and Brian McCann, the regular from 2014-16, rank first and second in FanGraphs’ version of framing runs, which dates back to 2008, while Francisco Cervelli (the regular in 2010) and Chris Stewart (likewise in 2013) are among the top quintile for the period as well. Sánchez has only once been above average per our version of framing runs, but in BP’s version, he ranked 16th out of 62 catchers with at least 2,000 called strike chances with 7.4 runs in 2017; last year, however, he sank to 50th out of 64.

Likewise, Sánchez’s success rate at thwarting the running game has eroded, with his caught stealing rate declining annually since he broke in by nabbing 41% in 2016; he was down to 23% in 2019. Some of that may be a function of the pitchers he’s working with; via Statcast, his pop times have climbed from 1.90 seconds in 2016 to 1.95 in ’19, but that decline represents a drop from the 100th percentile to the 86th — still more than respectable.

Via BP’s suite of metrics, which I illustrated in the graph above, Sánchez has declined by a total of 12.7 runs from 2017 (6.6) to ’19 (-6.1). In his recent discussions with reporters, Swanson acknowledged the trend and the potential balance between blocking and framing. “His blocking got better and we saw regression in framing,” he told King on February 15. “There is a tradeoff in a lot of ways. You try to maximize one and there is a give and take.”

On the other hand, Swanson pointed to Garver’s success. Via Newsday’s Erik Boland:

“I think Mitch Garver is a case study of that last year, and his blocking actually improved. But to be honest with you, when I first started down this path, that was my thought, like, ‘Hey, our blocking may regress, our throwing may regress slightly, but if we’re capturing more strikes, that could be a net win.’ I think we can actually improve in all three categories. It’s not just to try to make Gary a better pitch-framer at the expense of everything else. We actually believe that he’s going to see gains in in all of his defensive game.”

Understandably, the new stance is a work in progress for Sánchez, who said via an interpreter after Monday’s start, “There were a couple of times where I felt I was in between, my rhythm was not as good. On some occasions the desired results were there.” To be fair, much of his focus was on getting in sync with Cole, who gave his new catcher positive reviews.

While Sánchez works to shore up his defense, he could stand for a rebound on the offensive side as well. Though he mashed a career-high 34 homers in 2019, he hit a lopsided .232/.316/.525. That was certainly a step up from his dismal, injury-marked 2018 showing (.186/.291/.406) but a far cry from the robust .284/.354/.568 he hit in 2016-17, when he burst on the major league scene by clubbing 20 homers in a 53-game rookie season and then followed up with 33 over the course of a full season. Last year’s 116 wRC+ ranked fifth among the 30 catchers who made at least 300 plate appearances (Garver broke out to rank first at 155), and so it feels weird to nitpick, but he was well off his combined 143 mark from 2016-17.

Sánchez’s average exit velocities have consistently landed in the 90-91 mph range during his full seasons. Last year, he had the majors’ third-highest maximum exit velo (118.3 mph), tied for ninth with 31 events with velos of at least 110 mph, and placed in the 84th percentile with his overall average of 91.0. He cut his groundball rate to 32.1% (down from 42.9% in 2018), but he also chased pitches outside the zone with greater frequency than before, struck out a career-high 28.0% of the time, up from 23.5% in 2016-17, and produced just a .244 BABIP, 64 points removed from those first two seasons. Granted, the seemingly endless series of groin strains has cut into his speed and limited the extent to which he can max out while running, but a player who once looked like a potential MVP candidate is now merely another solid cog in a strong lineup. With Giancarlo Stanton already sidelined and Aaron Judge nursing shoulder concerns, a return to his 2016-17 form — on both sides of the ball — would be a most welcome development.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Is his new stance likely to hurt his fielding, especially bunts and popups?

It won’t, he’ll be off his knee in the case of a bunt attempt before contact and for pop ups, it’s not like a crouch is an easy thing to bounce out of even for younger guys.

I’m more concerned by his throwing hand laying so exposed on his thigh. Hide that bad boy Gary!

Then why wouldn’t every catcher do this?

Because not every catcher/organization is quite ready to jump aboard quite yet. But we know what Hedges can do behind the plate, and this is how he does it.