How Does Mike Soroka Do It?

Baseball has changed a lot in the last five years, so much so that watching a game from 2014 already feels like a blast from the past. Offense was low, sinking fastballs were everywhere, and groundballs and defense were the order of the day. 2019 hardly feels like the same game — unless you’re watching Mike Soroka, that is. Though Soroka is only 21 years old, he pitches like he’s from a previous era. In a time of four-seam fastballs, Soroka pitches off of his sinker — he’s throwing only 16% four-seamers this year and 46.3% two-seam fastballs. In a world of exciting high-velocity young aces, Soroka sits around 93 mph. In a world of home runs, he has allowed only one all year. In short, Mike Soroka doesn’t fit in 2019. How does he do it?

As is almost always the case with pitching, Soroka isn’t doing one specific thing that makes him dominant. If it were that straightforward, that easy to reverse engineer, everyone would be doing it. Still, dominant is an apt description of Soroka’s 2019 season. He’s posted a 1.38 ERA over ten starts. His FIP is nearly as jaw-dropping — fifth in baseball at 2.70. Has he been a little lucky that only 2.9% of fly balls hit against him have become home runs this year? Certainly. Still, though, his 3.5 xFIP is no slouch, 20th-best among qualified starters.

Great pitching is always interesting, but the way Soroka is doing it is what makes him unique. His 21.9% strikeout rate is below league average, not the kind of thing you can say about most excellent pitchers. His 6.5% walk rate is better than average, but not absurdly so — it’s merely 38th-lowest among qualified starters. In short, Soroka is an evolutionary Mike Leake, or 2019’s Miles Mikolas. He’s effective in a way that resists categorization, that belies the easy tropes of analysis. Why is Mike Soroka good? He’s good because he gets every little edge he can.

Pinpoint Command

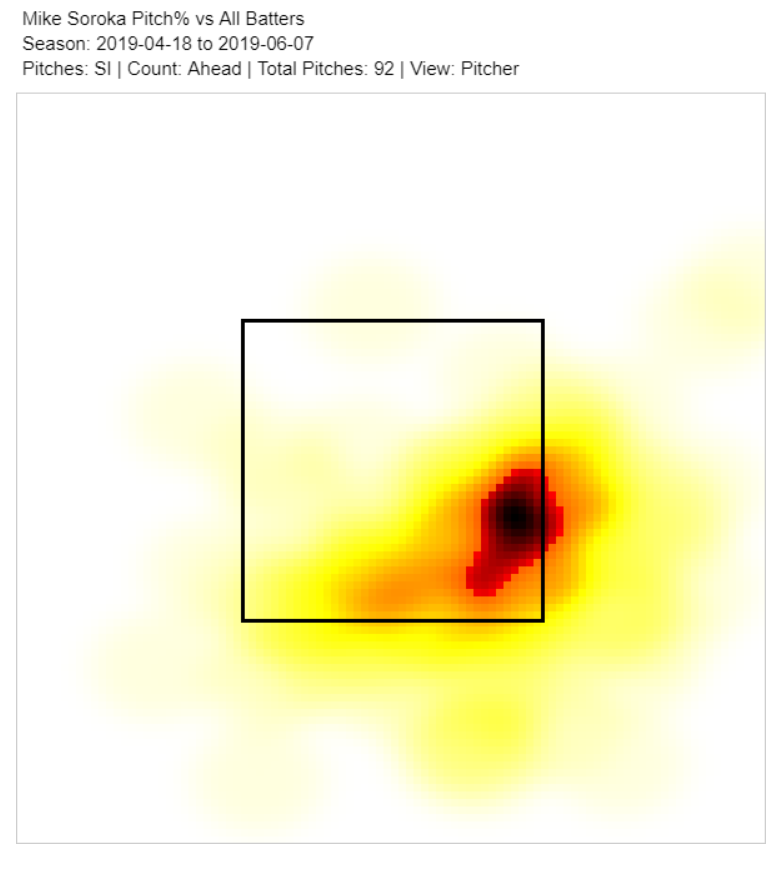

If a pitcher doesn’t have blinding velocity and lights-out secondary pitches, another way to get by is by putting the ball exactly in the right place. Soroka is a great example of this. How do you put hitters away when you’re ahead in the count but use a two-seam fastball, the pitch least likely to get a swing and a miss? You put that fastball in a spot where a batter can’t do anything with it. Take a look at where Soroka locates his two-seam when he’s ahead in the count:

That’s exactly where you want to throw a sinker when ahead in the count. The batter can’t really afford to let the pitch go by — a lot of these fastballs would be called strikes, after all. At the same time, that’s not exactly the kind of pitch at which hitters love to swing. Keeping sinkers to the edges of the plate is a great way to limit damage on contact. Two-seam fastballs that hit the edges of the strike zone (either just inside or just outside) have been hit to the tune of a .344 wOBA when put in play this year. That’s a wholly acceptable outcome when you add in the fact that some of them result in taken strikes and some in swings and misses.

Compare those precisely located fastballs to what happens when you leave a pitch over the plate, and the value of control becomes evident. Two-seam fastballs over the heart of the plate are a pitcher’s nightmare when batters put them in play — they’ve produced a .418 wOBA this year, the kind of offensive production batters dream of. Put a two-seam fastball over the heart of the plate into play, and you’re producing like George Springer or Freddie Freeman’s overall line. Put a fastball that dots the corner of the zone into play, and you’re producing like Ji-Man Choi’s 2019 — still acceptable, but substantially worse. That, in a nutshell, is why Soroka’s location is so important.

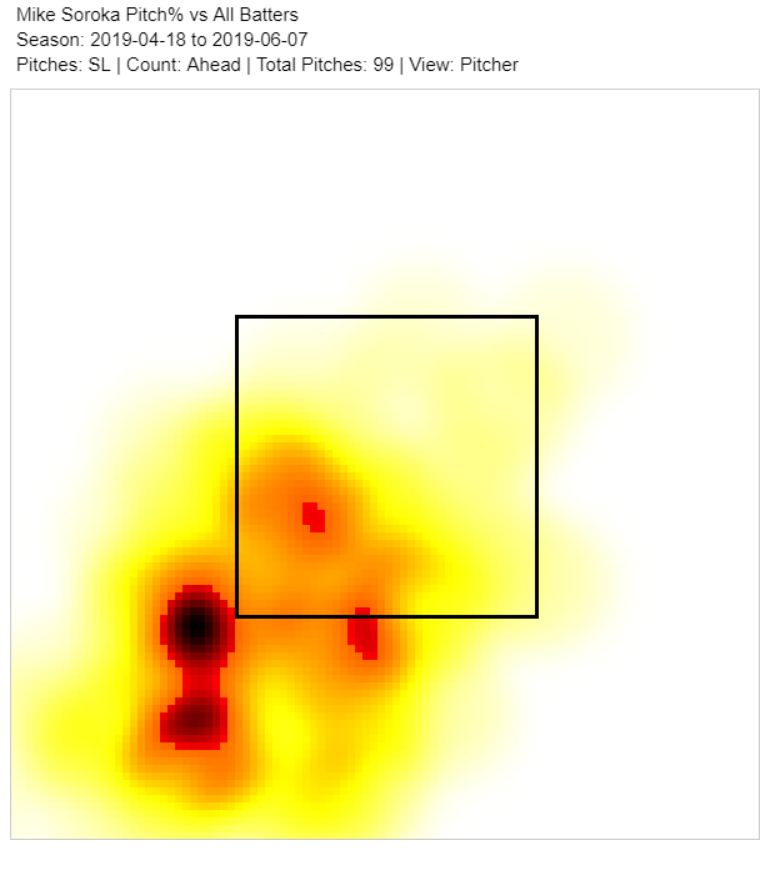

Fastball command isn’t the only tool Soroka has at his disposal when he gets ahead in the count. He also builds off of his fastball by starting his slider in a similar location before it crashes down and away. His control isn’t quite as pinpoint with a slider as it is with a sinker, but it still gets the job done:

Those zone locations look good in the abstract, but what does that look like in action? Well, imagine you’re Brian Anderson here. It’s a 1-2 count, and you see fastball out of Soroka’s hand:

Have to swing, right? Just like that, the sinker’s fade kicks in, and it’s a pitch just off the plate inside. The true conundrum of being a batter facing Soroka, though, is that his slider starts out on a similar plane. Offer at what you think is a fastball, and you might end up like Hunter Renfroe, swinging at air:

Using a two-seam fastball limits a pitcher’s strikeout upside, but it doesn’t have to completely eliminate the strikeout, and Soroka’s ability to hit corners and play pitches off of each other lets him get an average amount of strikeouts overall with a two-seam. Why does that matter? Well, Mike Soroka with an average amount of strikeouts is great, because when batters do put the ball in play, they’re not doing anything with it.

Contact Management

As much as baseball has changed since 2014, one thing is as true as it ever was: groundballs can’t leave the park. One way to succeed despite a middling strikeout rate is to keep everything on the ground. This seems pretty straightforward, but it’s easier said than done. Batters know the math, and they’re trying to put the ball in the air as much as possible. So far this year, though, Soroka has been up to the task. Here are the 10 best starters when it comes to GB/FB ratio this year:

| Player | GB/FB |

|---|---|

| Dakota Hudson | 3.07 |

| Mike Soroka | 2.97 |

| Max Fried | 2.43 |

| Luis Castillo | 2.40 |

| Sonny Gray | 2.20 |

| Brad Keller | 2.19 |

| Marcus Stroman | 2.09 |

| German Marquez | 1.99 |

| Brett Anderson | 1.90 |

| Hyun-Jin Ryu | 1.88 |

Dakota Hudson has been marginally more ground-based, but no one else comes close to the two young pitchers when it comes to keeping the ball on the ground. This is new territory for Soroka — he got more grounders than average while in the minors, but nothing like his current rate. Cutting back on four-seam fastballs to focus on his two-seam seems like it unlocked something, though, and his new groundball rate goes a long way towards explaining how he’s allowed only one home run this year.

In addition to all the grounders, Soroka has been masterful at getting batters to hit pop-ups. 17.6% of the fly balls batters hit against Soroka don’t leave the infield, the third-highest rate in baseball. Pop-ups are the only batted ball type that produces worse outcomes than grounders, and Soroka is great at inducing both of them. Here’s one way to think about contact quality: imagine a world where pitchers control what type of batted ball they allow, and nothing more. All grounders are created equal, in other words, as are all fly balls. Look at batted balls this way, and Soroka is one of the best players in baseball at controlling damage.

| Player | wOBA on Contact |

|---|---|

| Dakota Hudson | .346 |

| Luis Castillo | .350 |

| Sonny Gray | .351 |

| Mike Soroka | .353 |

| Marcus Stroman | .356 |

| Cole Hamels | .360 |

| Clayton Kershaw | .361 |

| Brett Anderson | .370 |

| Stephen Strasburg | .370 |

| Frankie Montas | .371 |

As good as fourth in baseball sounds, it might be underselling Soroka. Line drives are a really high-value batted ball type for hitters, but they’re also unpredictable. Pitchers’ line drive rates are nothing approaching stable — your best bet when predicting a pitcher’s future line drive rate is probably just whatever the league average is. Force every pitcher’s line drive rate to be exactly league average and use GB/FB ratios to work out the rest of the batted balls, and Soroka looks even better.

| Player | wOBA on Contact |

|---|---|

| Mike Soroka | 0.349 |

| Dakota Hudson | .356 |

| Sonny Gray | .363 |

| Max Fried | .365 |

| Brad Keller | .366 |

| Clayton Kershaw | .368 |

| Luis Castillo | .370 |

| Frankie Montas | .372 |

| Marcus Stroman | .372 |

| Cole Hamels | .374 |

None of this considers whether Soroka is actually capable of limiting contact quality, and generally speaking, it’s a safe assumption that most pitchers don’t have magical weak-contact powers. So far this year, however, Soroka has done an excellent job of preventing loud contact. His 2.9% HR/FB rate isn’t quite as wild as it looks given how many of his fly balls are pop-ups, but it’s still pretty wild. No starter has allowed fewer barrels per batted ball this year — Soroka has allowed all of five barrels all year over 178 balls in play. Will this skill continue? Even if it doesn’t, Soroka allows potentially the best mix of contact in all of baseball, but if he really does limit hard contact, he could be even better.

Pitch Sequencing

The two previous skills go hand-in-hand. If you have a sinker and precision command, it’s easier to get groundballs, and getting a lot of groundballs lets you lean more on your in-zone sinker/out-of-zone slider combination. It’s a virtuous circle. But to get the most out of his pitches, Soroka has done something else. It’s subtle, but I believe it’s helping him reach the level of performance he’s achieved this season. Mike Soroka is mixing his pitches tremendously well this year, keeping batters off balance and making every pitch look better.

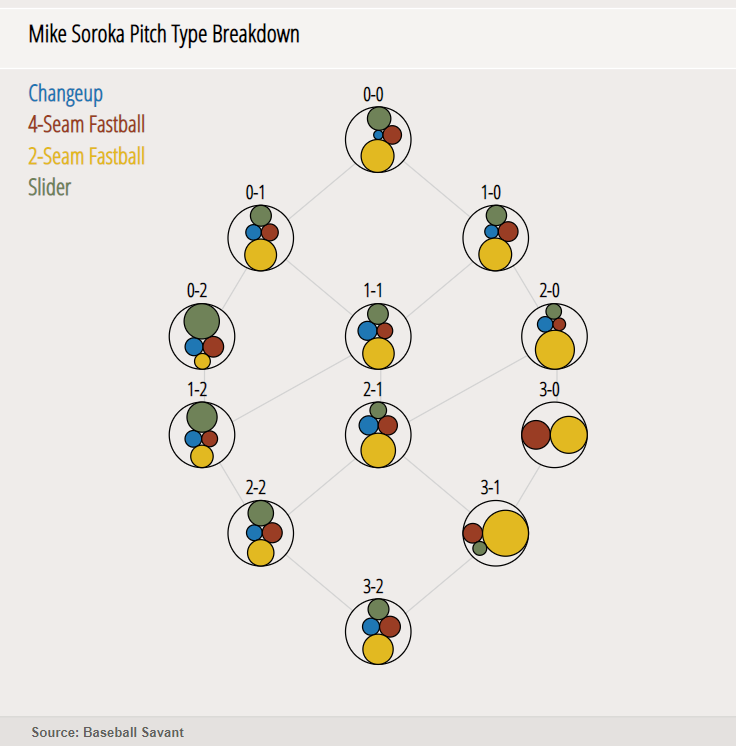

Take a look at Soroka’s pitch distribution in each count this year, courtesy of Baseball Savant:

Each circle represents the relative frequency of each of his pitches for a given count. This chart is a thing of beauty. Soroka throws his slider, four-seamer, and two-seamer in roughly the same mix on 0-0, 1-0, 0-1, 1-1, 1-2, and 2-1 counts. There’s no giving in and throwing a fastball over the plate on 1-0 or 2-1, no hard-and-fast rule that it’s all fastballs until he gets ahead in the count and all breaking stuff afterwards.

The rule of thumb of throwing fastballs in hitters’ counts is used less often than ever in modern baseball, but Soroka still mixes his pitches a good deal more than the average starter. He throws his two-seamer between 48% and 54% of the time in most counts, and even mixes in some 3-1 sliders and 0-2 fastballs. Soroka is a cipher on the mound, and that prevents hitters from sitting on any particular tendency.

When you’re forced to look at a pitcher’s sequencing to figure out why he’s effective, it’s a good bet that the obvious culprits (whiffs and strikeouts) don’t explain the production, and that’s definitely the case with Soroka. Watching one of his starts isn’t like seeing Chris Sale, a whirling mass of limbs that produces impossibly-angled sliders and swinging strikes galore. It’s more like watching Kyle Hendricks, sinkers and changeups just eluding the fat part of the bat as groundballs end at-bat after at-bat. Still, though, whoever he resembles, Mike Soroka has been one of the best pitchers in baseball this year.

Will it continue? Will the little edges that Soroka gets continue to add up to a sub-2.00 ERA? Well, probably not. That’s true for any pitcher, though. Even if things break a little worse for him, there’s a foundation here that could make him successful for a long time. Striking out a lot of batters always plays. Tremendous fastball velocity always plays. It’s easy to forget, though, that inducing a tremendous number of grounders and pop-ups is still a really valuable skill. Mike Soroka may never strike out 35% of the batters he faces or throw 99, but he’s one of the best pitchers in baseball right now because he does everything else right.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

219 babip

2.9 HR/FB

He is a grounder machine but this is not close to sustainable.

I don’t know how interesting the insane BABIP/homer suppression is, because that’s going to regress, at least a little bit, probably more than that. And also, BABIP has a bunch of factors that go into it, so that attributing all of it to the pitcher is usually a fool’s errand.

But the grounders are really interesting, because that’s potentially sustainable and because it reduces the dependence of his profile on the homer suppression. The dude’s xFIP is 3.50, which Ben notes but I wish he had talked about a little more. That’s because of the grounder rate; regressing the grounder rate back towards league average just doesn’t have that big of an effect on the FIP because he puts so many balls on the ground.

xFIP doesn’t “normalize” a pitcher’s ground ball rate. It takes the contact mix as given, then assigns a league-average HR/FB rate to whatever fly balls the pitcher has actually allowed. (I’ve always wondered if infield flyballs are counted as part of that, though; if they are, it seems like guys who are sustainably able to generate lots of pop-ups might be underrated by xFIP.)

Alex Chamberlain recently looked into this. Iffb’s do go into hr/fb, so like you said, sustainable pop up guys might be undervalued.

https://fantasy.fangraphs.com/fixing-xfip/

Not clear to me if it’s a skill that carries over from year to year. Skimming the leaderboards since 2015, it seems like maybe Scherzer, Odorizzi, and R.A. Dickey are legitimately good at it, but a lot of other guys pop in and out of the leaderboard randomly.

Ah jeez, that’s a typo. I meant regessing the HR/FB rate back. Thanks.

I think the grounder rate is somewhat sustainable and that is why he does project for a below average HR rate. But what is not sustainable is his 3% hr/fb

No one is claiming it’s sustainable. The argument is that Soroka does some things that are difficult to see in a glance at his stats, and those add up to an edge that may help him stay ahead of his expected regression. That’s not the same as saying “he won’t regress.”

Ultimately, you either think he’s better than 3.90 ERA RoS (STeamer/BAT RoS) or you don’t.

Most of this comment board thinks he’ll be below 3.90. That’s a bold claim, and one I would be happy to fade at decent odds.

I don’t think he’ll be dramatically better than that, but I would take the under.

Worth bearing in mind a 3.90 ERA in this environment from a 21-year-old is extremely valuable.

Doubt Canadian Jesus at your own risk. Maple Maddux cares not for your “trends.”

I second that!

Then it is a good damn thing that this article did not at all try to make the claim that it was sustainable. Nor does it appear anyone else is making that claim.

You’re right: no one’s bold enough to make the claim outright. Instead they are waffling that it’s “kinda” sustainable, trying to take credit for any rest of season ERA below 4.00.

Braves fans downvoting? His hr/9 is 0.14, the most optimistic projection is 4 times as high, steamer is 7 times as high. Don’t get me wrong he is a solid pitcher and his 15% k-bb isn’t bad either and you should explain it to play up due to his grounder tendency but still this is nowhere near sustainable.

No, it’s people annoyed that you’re reiterating a point already explicitly made in the lead paragraphs of the article yet somehow acting like you’re being contrarian and pointing out something that the author missed. Perhaps you’re just a terrible reader, or else you jumped down as soon as you saw the headline to in order to have “first comment” with what you hoped would seem like a novel insight. How adorable.

Deleted, not worth debating

“I admit I have commented before reading the article”

Um…so. Yeah.

I’m not a braves fan and I downvoted, because it’s like “Cool Story Bro” or “Thanks Captain Obvious”. No one anywhere is saying these results are sustainable but the author points to why and how he has been achieving this success so far.