Here Is What the Shift Has Done

Shifts. They’re everywhere! They take different forms, some more extreme or unusual than others, but this is, without question, the era of non-traditional defensive positioning. Defense will never again look like it used to, because there’s no reason to go back. I was watching a WBC game the other day and the broadcasters pointed out that one of the teams wasn’t shifting. That’s what’s newsworthy now. We take defensive movement for granted.

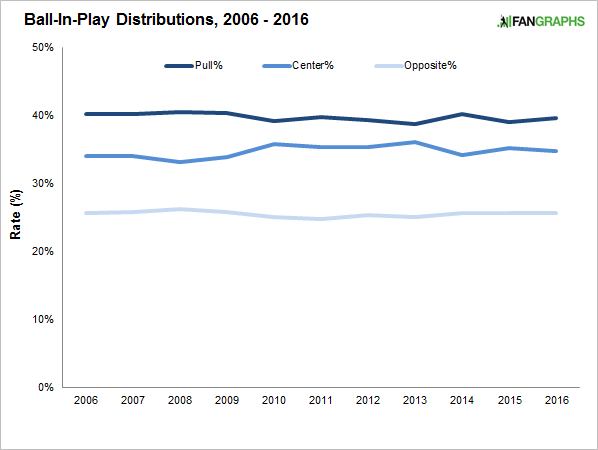

This is an InstaGraphs post, instead of a front-page post, because there’s nothing surprising about the images or data that follow. I just want to show you, graphically, how the sport has changed over the past decade or so. You know we have numbers like pull rate, correct? That information, on the league-wide scale, seems to be stable going back to about 2006. Here is how batted balls have been distributed:

Super consistent. Balls are being pulled as often as before, and they’re being sent the other way as often as before. Maybe you expected that, or maybe you didn’t! I’m not in your head. Let’s just move on to the more interesting stuff. Here is league-wide directional wRC+:

The pull line has stayed consistent. Yet there are recent increases in the other two lines. How about we focus on just batting average on balls in play?

Pull line down. Opposite line up! This is all very intuitive. To go one step further, here is the same plot as above, only in this one I’ve included only ground balls:

I could’ve broken out right-handed hitters and left-handed hitters, but these days there are adjustments against hitters on both sides. And anyway, all this does is prove what you presumably would’ve already guessed. Pulled ground balls were never great, but they used to be hits more than a fifth of the time. That rate has dipped, because almost everyone pulls the majority of their grounders, so that’s where the defenders are going in greater number. Grounders back up the middle have seen a slight rise in success, with a weird spike in 2014. And then the line for grounders to the opposite field has taken off. The BABIP as recently as 2009 was .287. Last year it was .373. You know what those grounders look like when the defenders have moved. They’re frequently routine rollers, hit to an area where nobody is.

The end result of all this? A decade ago, the league BABIP on grounders was .239. Last season, the league BABIP on grounders was .239. That isn’t meant to suggest that shifting in general is a complete waste of time. It’s just — it’s complicated. Baseball will find its own levels, regardless of what you want or expect.

Jeff made Lookout Landing a thing, but he does not still write there about the Mariners. He does write here, sometimes about the Mariners, but usually not.

I guess the question, since the BABIP on grounders has stayed the same, is how much of that is due to hitters adjusting? That is, we know some hitters consciously try to beat the shift, and others will not adjust at all. The key is what percentage are in each camp? And if more extreme pull hitters more often bunt or otherwise try to beat the shift, will that change the BABIP on grounders?

My guess is that it is going to stay about the same: if hitters adjust, the fielders adjust back (not shift as often nor as extremely). Then, once fielders stop shifting so much, the hitters go back to pulling the ball, and so on, and so on. With the end result that the BABIP stays the same.