Patrick Corbin’s Game-Changing Tweak

Earlier this week, Patrick Corbin signed with the Nationals as a free agent, getting six guaranteed years and $140 million. It’s a bigger deal than Yu Darvish got last offseason, as another Tommy John surgery survivor. In part, Corbin got that money because the Nationals felt like spending, as they sometimes do. It’s a way for them to brace for the potential loss of Bryce Harper. But the bigger factor here is that Corbin just pitched like an ace. He doesn’t have a track record of doing so, but obviously, there’s belief in his breakout.

This past year, 140 different pitchers threw at least 100 innings. Corbin threw exactly *200* innings. Out of that group, he finished with a top-ten K-BB%, and he finished with a top-five park-adjusted FIP. Corbin wound up with a lower FIP- than Max Scherzer, if you can believe it. So much of the difference came down to his newfound dominance of righties. His K-BB% against righties two years back was 11%. This past year, he got up to 25%. That’s a hell of a mark for a southpaw.

So what was it, then, that got into Corbin? How did he break out in the way that he did — especially given the sudden, unexplained drop in velocity that took a few months to recover? Maybe Corbin felt healthier than ever. Maybe he was spotting his two-seamer a little better around the edges. And as I wrote in April, Corbin made more use of his breaking ball than ever, dropping his rate of fastballs under 50%. He also nearly eliminated his ineffective changeup. Every improvement has multiple causes, but I want to quickly highlight one fun little tweak. It’s something I mentioned in April, but now there’s a lot more data, and I’ll make use of images from Texas Leaguers and Baseball Savant.

Corbin has thrown two fastballs, a slider, and a changeup. The changeup was never good, so he phased it out, but he also replaced it with something else. It’s a pitch that’s been labeled as a curveball. Here’s a plot of his horizontal and vertical pitch movements, with 2017 on the left and 2018 on the right:

You look at that and it might look strange. Corbin folded in a curveball, but the curveball broke…pretty much exactly like his slider. What’s the point of two different pitches, if the two pitches are the same pitch? There’s more going on here, though. Let’s now look at the same information, except this time including the effect of gravity:

Now there’s separation. The pitch labeled as a curveball moved in the same way, but by folding in gravity, you see far more vertical break. How come? The curveball effectively worked as a changeup variety of the slider. Here’s another set of plots, which has velocity on the y-axis:

By movement, the curveball and the slider looked the same. They might as well have been the same pitch. But there are very distinct velocity bands you can see on the right, with the slider in the low-80s, and the curveball in the low-70s. I don’t know if Corbin used a different grip, or if he just held the ball deeper, or if he even just slowed down his arm. But he basically got two pitches out of one, which is something he hadn’t done before.

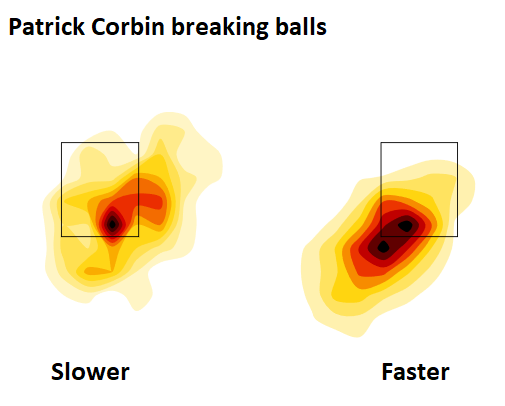

Gone was the changeup to his fastball. In was the changeup to his slider. Based on the results, this was the better combination. And I should point out that Corbin used the two breaking-ball varieties differently. For the following heat maps, I split the pitches apart at 78 miles per hour:

Most of the time, Corbin used the slower breaking ball early, to get ahead or to get back into the count. The firm slider was the putaway pitch, and Corbin specialized at finding the back feet of righties. By average vertical location, the slower breaking ball was more than six inches higher than the faster breaking ball. Here you can see the pitches in action. A slow breaking ball at 74:

And then a firmer breaking ball at 81:

Obviously, everything worked. Corbin’s first-half strikeout rate was 30%. His second-half strikeout rate was 31%. It’s not that he could never master a changeup — it’s that he was just thinking about the changeup wrong. He changed up against his best pitch, and he had the best season of his career.

It feels like a good thing, like a promising thing, although I do wonder if it’s a tendency hitters might pick up on. Maybe hitters will start to eliminate the slower breaking ball later in the count, despite the fact they might’ve seen the pitch early. But also, maybe it doesn’t work like that. Or maybe Corbin will start to spread the pitch out into different counts, to keep hitters honest. It’s always a game of adjustments, for everybody, and Corbin will eventually have to adjust to something. Right now, though, he’s gotten ahead with his own adjustments. It’s going to be up to the hitters to make him make another change.

Jeff made Lookout Landing a thing, but he does not still write there about the Mariners. He does write here, sometimes about the Mariners, but usually not.

To go on a bit of a tangent, one caveat about looking at Corbin’s number is the introduction of humidor in Chase field.

2018 Arizona pitchers are most likely overrated by ERA-, FIP- while Arizona hitters are underrated by wrc+.

2015-17 Diamondbacks

Home ERA 4.49 OPS 0.797

Away ERA 4.04 OPS 0.712

2018 Diamondbacks

Home ERA 3.69 OPS 0.719

Away ERA 3.76 OPS 0.695

Yep, slipped my mind. Of course you are correct. Corbin’s “true” FIP- should be a few points worse than what’s shown.

I’m more surprised how small the split is between home and away ERA last year. Isn’t the usual standard like half a run?