Introducing Ryan Zeferjahn, Basically Unhittable and Largely Anonymous

Hello there, FanGraphs readers. Today I’d like to tell you about a reliever on the Los Angeles Angels. Now sure, just last week, I wrote about how much help the Angels needed on the pitching front, and in the bullpen in particular. And sure, the guy we’ll be discussing today has a 4.05 ERA and a 4.08 FIP so far this year, not exactly stud closer numbers. Was he a trade throw-in last summer, one of four lottery tickets the Angels landed in exchange for a reliever in a contract year? He sure was. But that doesn’t change the fact that he’s interesting. So I’d like to introduce you to Ryan Zeferjahn, the best reliever you’ve probably never heard of.

The first thing you should know about Zeferjahn is that his primary pitch is weird. Everyone calls it a cutter, and in many ways, that makes sense. Let me show it to you in action:

Yep, that’s a cutter. It’s 90-ish mph, with less rise and arm-side fade than a four-seam fastball, and it makes batters look uncomfortable because they can’t quite classify whether it’s a fastball or a breaking ball. Miguel Vargas read that pitch as inside, and then it held the plate thanks to unexpected cut. But Zeferjahn’s cutter has, for lack of a better way of saying it, a lot of cut even for a cutter. This isn’t something you would pick up from watching a GIF or two, but that pitch has about six inches of glove-side break.

How much break is six inches? Well, hard cutters like Zeferjahn’s typically break 2-3 inches to the gloveside. That means his gets around three inches of unexpected movement relative to the cutters that opposing hitters see night in and night out. There’s exactly one pitcher in all of baseball this year throwing a cutter with more velo and more arm-side run: Ben Casparius of the Dodgers. Casparius doesn’t throw his cutter very often, only 15% of the time, while Zeferjahn uses his half the time. In other words, the movement profile of this pitch is weird.

It gets weirder, too. Where does that extra movement come from? It’s not just that he can magically spin the ball more. He’s imparting the spin in a different direction. His cutter has less backspin than most. The average cutter thrown 88.5-90.5 mph features about 7.5 inches of induced vertical movement. That’s far less than a four-seam fastball, which gives a cutter its deceptive shape; hitters expect it to ride and fight gravity by more than it does, but there’s still plenty of backspin. Zeferjahn’s cutter has only about 1.5 inches of induced vertical break. In other words, from the hitter’s perspective, it completely dies.

Another way of saying that? Zeferjahn has an unremarkable four-seam fastball, 98 mph with league average drop. His cutter falls 20 more inches than that fastball, with a velocity gap of 8.3 mph. Chase Dollander, a starter you’d create in a lab to display prototypical pitch shapes, gets about 15 inches of vertical separation between the same two pitches with the same velocity differential. This cutter simply doesn’t behave like hitters expect it to.

In fact, Zeferjahn’s cutter is closer to a high-velocity slider than anything else. I get Ryan Helsley or Emmanuel Clase slider vibes from the pitch. It’s sharp and disruptive, with plenty of glove-side break and that weird, rise-less shape that batters simply don’t expect from something traveling 90 mph.

That puts Zeferjahn in a weird spot, but a great one. The pitch he throws most often, his bread and butter in nearly every count, looks like a closer’s out pitch, with a 23% swinging strike rate that would be right at home ending games. And unlike those closers, he’s flooding the zone with this baby; his 69% zone rate is one of the five highest marks in the game for any fastball, let alone any cutter.

With a primary pitch that good, you might assume that Zeferjahn would strike out the world, and you’d be right – he has faced 27 batters this year and retired 14 via strikeout. At-bats against Zeferjahn are like life, per Thomas Hobbes: nasty, brutish, and short. He even has two useful change-of-pace pitches in a riding fastball and a sweeping slider.

Those pitches are worth breaking down in greater detail, because they also help explain Zeferjahn’s strange line so far this year. As I’ve noted, his fastball is your average four-seamer, 98 mph with unremarkable vertical movement. He spots it above the strike zone when he’s ahead in the count. When he’s behind in the count – well, maybe one day we’ll find out. He’s thrown exactly one four-seamer with more balls than strikes in the count all year, and it was this 3-2 offering to Willy Adames:

His breaking ball – or maybe his other breaking ball, it’s hard to classify with a pitcher who mostly throws a bendy fastball in the strike zone – is an exaggerated version of his cutter, with big glove-side break. A montage of batters swinging at it looks like you’d expect:

Quite frankly, if you didn’t tell me who was throwing these pitches, you could convince me that this was one of the best relievers in baseball. Zeferjahn’s fastball looks good as a show-me pitch, his cutter is an enviable workhorse, and that sweeper is lethal. Stuff+ thinks it’s his best pitch, in fact, though I’d take the cutter any day. The point is, pitchers with this broad an array of plus options tend to do well.

Why don’t his overall run prevention metrics show it, then? How can a guy striking out more than half the batters he faces sport a FIP higher than 4.00? You have to look to what happens when he doesn’t strike his opponents out. So far, Zeferjahn has allowed six fly balls, and two have left the yard. Whoops. First, he got got by baseball’s funniest hack, the Isaac Paredes lift-and-pull scheme:

Then Corey Seager did Corey Seager things:

Truthfully, I’m not too upset about either of those. If Zeferjahn has a long career in the AL West, he can expect more of both. Want proof that it’s probably not worth getting worked up over? Look at a similar pitcher: 2024 Ryan Zeferjahn. He allowed 19 fly balls, none of which left the yard. He never had much issue with contact quality in the minors; command was always the sticking point. If your primary pitch goes 90 mph and is most notable for its deception, you’ll probably give up at least a few home runs when one of those pitches backs up and hangs over the plate, but most of the “avoid home runs” battle comes down to not letting sluggers make contact, and Zeferjahn is very good at that part of the equation.

That leaves me with two questions. First, can he keep throwing his cutter like this? The current shape seems a lot better than last year’s model to me. It sinks and runs more, putting it on the slider/cutter boundary. Every bit of unexpected break helps, and I’m particularly interested in his ability to prevent backspin. Plenty of hitters are swinging over Zeferjahn cutters this year where last year they made contact. Combine that with his newfound ability to throw the pitch in the zone, and you end up with the ludicrous contact numbers he’s currently posting. Bring back last year’s shape and location, and he’s more an interesting middle reliever than a strikeout machine.

The second question is whether Zeferjahn can keep the ball in the strike zone frequently enough to challenge opposing hitters. That was his greatest weakness in the minors; in 2023, he ran a hard-to-believe 19.6% walk rate over a substantial 43 innings in Double-A. Even this year, with his top-of-the-scale zone rate, he’s walking 11.1% of batters. That’s only three walks – we’re still squarely in sample size silly season – but sometimes he just loses control of the zone. Look at this sequence starting from 0-2 against Jung Hoo Lee:

The crazy part? He did this to Lee earlier in that at-bat:

Two of his three walks have gone like that, with four straight balls from an 0-2 count (the last one hardly counts — he got replaced mid-PA after a rain delay). It’s clear both from his minor league track record and from watching him pitch that Zeferjahn is prone to the occasional bout of wildness. It would be more surprising if that weren’t the case; the reason he debuted in the majors at age 26 instead of earlier is because he struggled to throw strikes in the minors, not because he didn’t flash huge strikeout stuff.

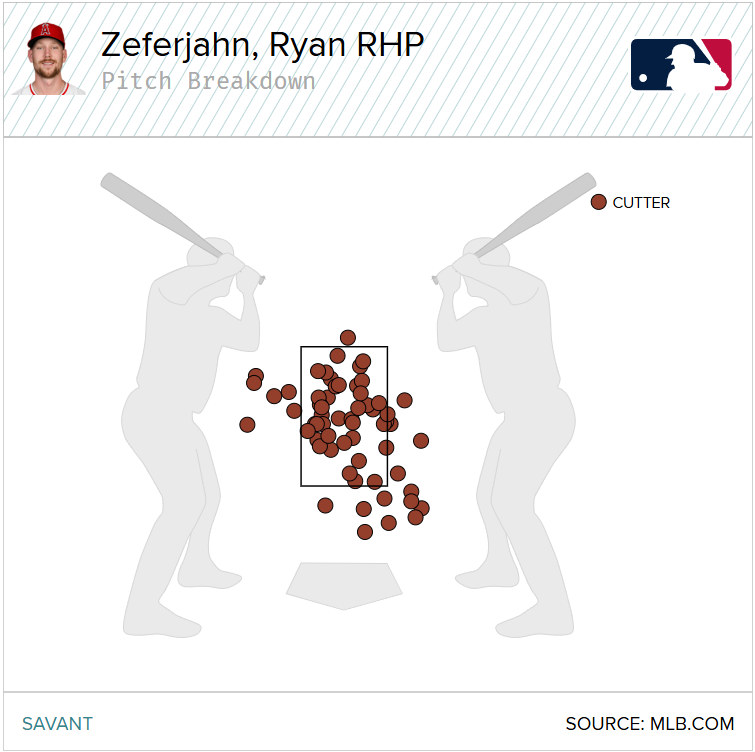

I wouldn’t bet on that suddenly improving. If you watch a lot of Zeferjahn outings this year, I think you’re going to see a fair number where neither he nor the guy he’s facing have any clue where the next pitch will end up. And that higher zone rate this year? It’s come from just aiming down the middle, a plan I wholeheartedly approve of:

There aren’t a lot of edges in there, to say the least. Hey, if batters can’t hit it, why nibble? Sometimes that will lead to Seager homers, of course, but the tradeoff seems good so far, and I think he’s going to keep doing it.

As is so often the case with these April check-ins on hot relievers who no one has really heard of, this isn’t Zeferjahn’s true talent level. He’s not going to keep striking out half the guys he faces, or putting up contact and zone rate numbers that resemble a video game more than reality. But unlike so many of these April check-ins, I think that Zeferjahn’s ERA and FIP are underrating his true talent level so far. If he’s the closer in Anaheim by year’s end, I would hardly be surprised. You can’t always put a timer on when relievers will figure things out, but for the moment, he has. As long as he maintains his current combination of pitch shapes and command, the data speak loudly: This is one of the top relievers in baseball.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Rock chalk!