JAWS and the 2022 Hall of Fame Ballot: Scott Rolen

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2022 Hall of Fame ballot. Originally written for the 2018 election at SI.com, it has been updated to reflect recent voting results as well as additional research. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule and a chance to fill out a Hall of Fame ballot for our crowdsourcing project, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball-Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

“A hard-charging third baseman” who “could have played shortstop with more range than Cal Ripken.” “A no-nonsense star.” “The perfect baseball player.” Scott Rolen did not lack for praise, particularly in the pages of Sports Illustrated at the height of his career. A masterful, athletic defender with the physical dimensions of a tight end (listed at 6-foot-4, 245 pounds), Rolen played with an all-out intensity, sacrificing his body in the name of stopping balls from getting through the left side of the infield. Many viewed him as the position’s best for his time, and he more than held his own with the bat as well, routinely accompanying his 25 to 30 homers a year with strong on-base percentages.

There was much to love about Rolen’s game, but particularly in Philadelphia, the city where he began his major league career and the one with a reputation for fraternal fondness, he found no shortage of critics — even in the Phillies organization. Despite winning 1997 NL Rookie of the Year honors and emerging as a foundation-type player, Rolen was blasted publicly by manager Larry Bowa and special assistant to the general manager Dallas Green. While ownership pinched pennies and waited for a new ballpark, fans booed and vilified him. Eventually, Rolen couldn’t wait to skip town, even when offered a deal that could have been worth as much as $140 million. Traded in mid-2002 to the Cardinals, he referred to St. Louis as “baseball heaven,” which only further enraged the Philly faithful.

In St. Louis, Rolen provided the missing piece of the puzzle, helping a team that hadn’t been to the World Series since 1987 make two trips in three years (2004 and ’06), with a championship in the latter year. A private, introverted person who shunned endorsement deals, he didn’t have to shoulder the burden of being a franchise savior, but as the toll of his max-effort play caught up to him in the form of chronic shoulder and back woes, he clashed with manager Tony La Russa and again found himself looking for the exit. After a brief detour to Toronto, he landed in Cincinnati, where again he provided the missing piece, helping the Reds return to the postseason for the first time in 15 years.

Though he played in the majors for 17 seasons (1996-2012), Rolen retired at age 37, and beyond sneaking over the 2,000 hit line, didn’t accumulate the major milestones that would bolster his Hall of Fame case. The combination of his solid offense and his defensive prowess — validated both by the eye test and the metrics — places his WAR and JAWS among the top 10 third basemen in history, but in his 2018 ballot debut, voters gave him a paltry 10.2%. While several conceded that they would have included him if space had permitted, his share only grew to 17.2% in 2019, but it more than doubled the year after, to 35.3%, then shot to 52.9% last year; not only did he follow the second-largest gain from 2019 to ’20 (18.1%) with the largest one from ’20 to ’21 (17.6%), he surpassed the 50% mark. Following the election of Gil Hodges by the Golden Days Era Committee, that means that aside from his company on the current ballot, every candidate who’s reached at least 50% has been elected either by the writers or a small committee. Like Larry Walker, a candidate who similarly benefited from strong defensive metrics that underscore his tremendous value despite counting stats that may not be eye-catching, Rolen has been taken more seriously by voters.

While getting to 75% this time around would require the fifth-largest jump of the post-1966 voting era, it’s not out of the question, but more likely, Rolen is still a year or two away from election. Given his slow start, that’s pretty remarkable.

| Player | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scott Rolen | 70.1 | 43.6 | 56.9 |

| Avg. HOF 3B | 68.4 | 43.1 | 55.8 |

| H | HR | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

| 2,077 | 316 | .281/.364/.490 | 122 |

Born in Evansville, Indiana in 1975 to a pair of schoolteachers, Rolen grew up in Jasper, a town of 10,000 roughly an hour away, and excelled at both basketball and baseball. On the court, he was a 6-foot-4 point guard versatile enough to play shooting guard or forward as well. In 1993, he made the Indiana All-Star team and was the Tri-State co-player of the Year, among other honors. Heavily recruited by colleges, he was offered hoops scholarships by UCLA, Oklahoma State, Alabama, and Georgia. He played all around the diamond and even pitched in relief before moving to third base full time. During his senior year, he was voted Indiana Mr. Baseball, as the top high school player in the state (he was runner-up in Mr. Basketball).

Though Rolen committed to Georgia for a basketball scholarship, he reconsidered when the Phillies chose him in the second round of the 1993 draft and offered a $250,000 signing bonus. After 25 games in rookie ball, he hit .294/.363/.462 with 14 homers as a 19-year-old in the A-level South Atlantic League in 1994, a performance that placed him at number 91 on Baseball America’s Top 100 Prospects list the following spring. He climbed to 27th in 1996 despite being limited to 86 games due to a broken hamate, and after a combined .324/.416/.515 showing in Double- and Triple-A, he was recalled on August 1 by the Phillies, who were in the midst of a 67-95 season. He went 1-for-4 with a double off the Cardinals’ Donovan Osborne in his debut. With incumbent third baseman Todd Zeile traded later that month, the 21-year-old Rolen hit .254/.322/.400 with four homers in 146 PA down the stretch, but his season ended on September 7, when a pitch by the Cubs’ Steve Trachsel fractured his right ulna.

The injury carried a silver lining, in that Rolen’s 130 at-bats left him barely eligible to be considered a rookie for 1997. He got his money’s worth out of the designation, climbing to 13th on the BA list and hitting .283/.377/.469 with 21 homers, 16 steals, and 4.5 WAR. He was unanimously voted NL Rookie of the Year, beating out the likes of Vladimir Guerrero and Andruw Jones. The Phillies, however, went just 68-94 under first-year manager Terry Francona, their fourth straight losing season since their 1993 NL pennant.

After signing a four-year, $10 million extension in the spring of 1998, Rolen broke out, bashing 31 homers, driving in 110 runs, and stealing 14 bases while hitting .290/.391/.532 for a 139 OPS+. Stellar defense (+12 runs according to Total Zone) earned him the first of his eight Gold Gloves; his 6.7 WAR ranked eighth in the NL. The Phillies climbed to 75 wins, and then 77 in 1999, before falling back to 65 in 2000. While Rolen hit a combined .284/.369/.539 for a 124 OPS+ and 9.2 WAR in those last two years, he missed 84 games due to a lower back strain (which ended his 1999 season on August 25) and a left ankle sprain. The team’s regression cost Francona his job.

Avoiding the disabled list for the first time in three years, Rolen put together another typical Scott Rolen season (.284/.375/.511, 25 HR, 107 RBI, 5.6 WAR) in 2001, but under the hood, things were far from normal. The Phillies tried to hash out another extension during spring training, but talks broke off due to Rolen’s concerns about the team’s payroll, which had ranked 20th in 2000; despite their large market, the Phillies received significant help from revenue sharing. Under Bowa, the team improved to 86-76, but the new manager did his part to alienate Rolen. In June, Bowa called him out after a series loss to the Red Sox, saying, “If the No. 4 guy [Rolen, the cleanup hitter] makes contact in either Boston loss, we sweep the series. He’s killing us.” Rolen was incensed. In August, Green said during a radio interview, “Scotty is satisfied with being a so-so player. He’s not a great player. In his mind, he probably thinks he’s doing OK, but the fans in Philadelphia know otherwise. I think he can be greater, but his personality won’t let him.”

“I don’t feel as welcome in this organization as I have in the past,” said Rolen in response. In November, he rejected a seven-year, $90 million extension, with options and incentives that would have elevated the total package to 10 years and $140 million. In December, Orioles owner Peter Angelos scuttled a tentative nine-player deal to the Phillies upon learning the potential cost of an extension.

When Rolen came to spring training, he elaborated on his discontent even while saying that he might have been “an idiot” for passing up such a lucrative deal. He told ESPN’s Jayson Stark, “Fans deserve a better commitment than this ownership is giving them. I’m tired of empty promises. I’m tired of waiting for a new stadium (not due until 2004), for the sun to shine.” A livid Bowa was caught on camera profanely telling general manager Ed Wade that Rolen should be traded; the footage never aired, but was leaked and became sports talk radio fodder. Still a Phil, Rolen was elected to start the All-Star Game even as he was being booed and portrayed as a clubhouse cancer, though a conciliatory Bowa called him “the best third baseman in the NL,” adding, “He’s earned that free-agency right. That’s the process, and he has earned it.”

Finally, on July 29, the Phillies traded Rolen, a Triple-A reliever, and cash to the Cardinals for third baseman Placido Polanco, starter Bud Smith, and reliever Mike Timlin. “I felt as if I’d died and gone to heaven,” Rolen — who grew up attending games in both St. Louis and Cincinnati — told ESPN’s Peter Gammons. His numbers improved after the trade (from a 123 OPS+ with 17 homers in 100 games to a 139 OPS+ with 14 homers in 55 games), and he finished with 6.4 WAR, good for seventh in the league. Before doing that, he signed an eight-year, $90 million extension for 2003-10.

Rolen’s post-trade performance helped the Cardinals win 97 games and run away with the NL Central. In his postseason debut, his two-run homer off the Diamondbacks’ Randy Johnson in the Division Series opener proved decisive. Unfortunately, in a collision with pinch-runner Alex Cintron in Game 2, he suffered sprains in four regions of his shoulder and collarbone “including a severe hyperextension of the three ligaments supporting his clavicle.” The injury ended his season; the Cardinals advanced to the NLCS but lost to the Giants.

Luckily, the injury didn’t carry over to 2003. Rolen played 154 games, his highest total since 1998, made his second All-Star team and hit .286/.382/.528 with 28 homers, 13 steals, and a 138 OPS+. While the advanced metrics gave mixed reviews on his defense (-4 Defensive Runs Saved but +7.7 Ultimate Zone Rating), he won his fourth Gold Glove. The Cardinals missed the playoffs, but rebounded to win 105 games and the NL pennant in 2004. Rolen set career highs across the board (.314/.409/.598, 34 HR, 124 RBI, 158 OPS+, 30 DRS, 9.2 WAR), with the last of those surpassing hot-hitting teammates Albert Pujols and Jim Edmonds. He won another Gold Glove but finished fourth in the NL MVP voting, sandwiched between the aforementioned teammates as Bonds won.

In a July 12, 2004 article in Sports Illustrated, Tom Verducci described Rolen’s appeal:

When he’s not flipping middle infielders like flapjacks, Rolen, 29, is playing the best third base of his generation, piling up more RBIs than Mike Schmidt did at the same age and carrying himself with such humility that even his teammates have to strain to hear him when he does speak. “Rolen’s the perfect baseball player,” Milwaukee Brewers manager Ned Yost says. “It’s his tenacity, his preparation, the way he plays. He tries to do everything fundamentally sound. And he puts the team first — there’s no fanfare with him.”

In an uneven October, Rolen went hitless in both the Division Series against the Dodgers and the World Series sweep by the Red Sox, but bashed three homers and went 9-for-29 in the NLCS against the Astros, with a pair of homers in their come-from-behind Game 2 victory and a two-run blast off Roger Clemens that put the Cardinals ahead to stay in Game 7.

While the Cardinals won 100 games and reached the NLCS in 2005, Rolen was limited to 56 games due to surgery to repair a torn left labrum, suffered in a collision with the Dodgers’ Hee-Seop Choi on May 10; after missing 34 games, he returned and attempted to play, but five weeks of hitting .207 without a homer made clear that he needed to go under the knife. Back to form in 2006 (22 homers, 126 OPS+, 5.9 WAR, the last sixth in the league), he made his fifth All-Star team and won his seventh Gold Glove.

The Cardinals weren’t nearly the powerhouse of 2004-05, barely winning the division with an 83-78 record, but they went on a roll in October. Rolen, however, was hampered by left shoulder fatigue and was benched twice by La Russa, who felt he wasn’t being forthright in conveying the condition of his shoulder — first for Game 4 of the Division Series against the Padres, then for Game 2 of the NLCS against the Mets. To that point, he was just 1-for-14, but upon returning, he carried a 10-game hitting streak through the remainder of the postseason. Though famously robbed of a homer by Endy Chavez in Game 7 of the NLCS, he homered off the Tigers’ Justin Verlander in the World Series opener, and went 8-for-19 overall.

The Cardinals won in five games, but the relationship between Rolen and La Russa was strained and would continue to worsen in 2007, Rolen’s final year in St. Louis. The 32-year-old third baseman hit a meager .265/.331/.398 with eight homers in 112 games, and while outstanding defense (+12 DRS) bolstered his value, continued left shoulder woes ended his season in late August; he underwent a bursectomy and the removal of scar tissue. After the season, Rolen told general manager John Mozeliak that he wanted out. “There’s absolutely no intention to accommodate Scott,” said an unsympathetic La Russa at that year’s Winter Meetings. “If he doesn’t like it, he can quit.”

Five weeks later, Mozeliak traded Rolen to the Blue Jays straight up for Troy Glaus; later, the GM hinted that spite may have played a role in the north-of-the-border destination, and conceded that the move weakened the team, calling Rolen “the only player I regret trading.” Rolen, for his part, was rather cryptic when asked later about his frosty relationship with La Russa, saying, “We’re different people with different morals… That’s as politically correct as I can say it, I guess.”

The trade may have alleviated that conflict, but before debuting for the Jays, Rolen broke a knuckle on his right middle finger and lost the fingernail completely due to a mishap during a fielding drill. He missed the season’s first 23 games, and later missed another 13 due to power-sapping left shoulder soreness. He finished at .262/.349/.431 with 11 homers in 115 games, though again, stellar defense (+9 DRS) bolstered his value (3.4 WAR).

Despite his sizzling showing in the first four months of 2009 (.320/.370/.476), Rolen and the Blue Jays were bound for nowhere. Desiring to be closer to home, he asked for a trade. On July 31, he was sent to the Reds — whose general manager, Walt Jocketty, had traded for Rolen as the Cardinals’ GM in 2002 — for Edwin Encarnación, Josh Roenicke, and Zach Stewart. Jocketty desired Rolen’s leadership as much as his ability, saying, “He will bring a lot to this ballclub that’s been lacking.”

(While today, the move appears imbalanced because Encarnación, a defensively challenged 26-year-old third baseman at the time, blossomed into an All-Star slugger, that wouldn’t happen for another three years; in fact, the Jays lost him to the A’s on waivers in November 2010, then re-signed him after he was non-tendered.)

Rolen suffered a beaning-related concussion in his second game as a Red. After sitting for two days, he homered in his first plate appearance back, but post-concussion syndrome soon sent him to the DL. “I’m just in La-La Land out there,” he said. “I have headaches I can’t shake.” Despite the injury, Rolen finished with a 116 OPS+, 17 DRS and 5.2 WAR, his highest total since 2006. In December, a contract restructuring converted his $11 million salary into a three-year, $24 million extension.

The deal paid off in 2010. Despite suffering lower back spasms, at age 35 he made his sixth All-Star team, won his eighth and final Gold Glove, hit a Rolenesque .285/.358/.497 with 20 homers, a 126 OPS+ and 4.1 WAR, and drew praise for his clubhouse leadership. The Reds, who hadn’t finished above .500 since 2000 and hadn’t made the playoffs since 1995, went 91-71 and won the NL Central. No-hit by the Phillies’ Roy Halladay in the Division Series opener, they were quickly dispatched; Rolen went just 1-for-11 while striking out eight times.

Rolen spent two more seasons in Cincinnati, but protruding discs in his lower back and problems with both shoulders — culminating in offseason surgery to remove bone spurs and fragments from the perennially troublesome left one — limited him to a total of 157 games, 13 homers, an 86 OPS+ and 2.2 WAR. The Reds did win the NL Central again in 2012, but squandered a two-games-to-none lead in the Division Series against the Giants, who beat them in five games and went on to win the World Series. Though he collected two hits in Game 5, Rolen struck out with two men on base in the bottom of the ninth against Sergio Romo, ending the Reds’ season. Afterwards, he conceded that he was mulling retirement, but hadn’t made up his mind. Teammates again lavished him with praise, with Ryan Ludwick saying, “A Hall of Famer, in my opinion, no doubt about it. I played with him in St. Louis, too, and he’s a gamer, a guy that goes about his business the way you want to teach a 3-, 4-, 5-year-old kid. He’s a grown man and he plays the game every out, every pitch at max intensity.”

Rolen remained on the fence about retirement. Both the Dodgers and Reds showed interest that winter, but he never did play again, putting the wraps on his stellar career.

…

At first glance, Rolen’s case for Cooperstown appears respectable but not overwhelming. Despite his eight Gold Gloves and seven All-Star appearances, his Hall of Fame Monitor score of 99 is a whisker below “a good possibility,” and his postseason line (.220/.302/.376 with five homers in 159 PA) offers little help outside of his stellar 2004 NLCS and ’06 World Series performances, not that those weren’t important. Regular season-wise, his totals of 316 homers and 2,077 hits don’t scream instant enshrinement, though at least he’s on the right side of “The Rule of 2,000,” though that may become less important with the recent election of Tony Oliva, the first post-1960 expansion era player with fewer than 2,000 hits (1,917); it’s worth noting that the lowest total for an expansion era non-catcher elected by the BBWAA just fell from 2,322 (Willie Stargell) to 2,160 (Walker) on the 2020 ballot.

Beyond that, Rolen was a model of consistency who rarely put up extreme numbers or made a splash on the leaderboards. He never ranked among the league’s top 10 in hits, homers, or batting average; he did so just once in walks, OBP, and SLG, and in OPS+ twice. Nonetheless, his numbers stand out relative to his position. His .490 SLG is fifth among players with at least 7,000 PA who spent most of their careers at the hot corner, but that’s in part a reflection of playing in a high-scoring era; contemporaries Aramis Ramirez (who was on last year’s ballot) and Matt Williams are fourth and sixth, and nobody’s stumping for their election. Adjusting for the environments in which Rolen played, his 122 OPS+ ranks ninth on a list topped by six Hall of Famers (Schmidt, Eddie Mathews, Chipper Jones, George Brett, Wade Boggs, and Ron Santo), though none of the other players in the top 15 are enshrined. Via batting runs, the offensive component of WAR, Rolen’s 16th at 234, behind a mix of Hall of Famers, perennial All-Stars, and 19th century obscurities. Among his contemporaries, only Jones (who’s first at 558), David Wright (285) and Beltré (257) outrank him; the latter doing so only with the benefit of 3,612 additional plate appearances.

It’s Rolen’s combination of strong offense and elite defense that’s his true selling point. He’s considered by many to be the best defensive third baseman of his era, and has both the hardware and the advanced metrics to bolster that claim. His eight Gold Gloves are more than any third baseman besides Brooks Robinson and Schmidt, and he’s third at the position in fielding runs, 175 above average via a combination of Total Zone (1996-2002) and Defensive Runs Saved (2003-12), with only Robinson (294) and Beltré (218) ahead. Rolen had 11 seasons where he was at least 10 runs above average in the field (second only to Robinson) including five of at least 15 above average.

Rolen cracked the league’s top 10 in WAR a modest four times, but had six seasons of at least 5.0 WAR, tied for 10th at the position, and 11 of at least 4.0 WAR, tied for third with Boggs, behind only Schmidt and Mathews. That’s particularly impressive considering his career length. Take away his cup-of-coffee 1996 season, his injury-wracked 2005, and the two at the tail end of his career, and in 11 of the other 13 seasons, he was worth at least 4.0 WAR, which is to say worthy of All-Star consideration. Only in 2007 and ’08 did he play more than 92 games and finish with less than 4.0 WAR.

Thanks to that consistency, Rolen ranks 10th at the position with 70.1 career WAR, behind eight Hall of Famers plus Beltré, all of whom played at least 200 more games. He’s 1.7 WAR above the career standard at the position. His 43.6 peak WAR is a more modest 14th, but still 0.5 above the standard, and ahead of six enshrinees including Paul Molitor (who spent more time at DH). Rolen’s 56.9 JAWS ranks 10th, 1.1 points above the standard. Particularly at a position so drastically underrepresented in the Hall — there are 15 non-Negro Leagues third basemen, but 28 right fielders (counting Oliva), and 19 to 23 at every other position besides catcher — that’s a player who belongs in Cooperstown.

Rolen’s candidacy got off to an inauspicious start; his 10.2% debut was lower than the lowest post-1966 candidate to be elected by the writers (Duke Snider, 17.0% in 1970), while his 17.2% in his second year surpassed only Bert Blyleven (14.1%) — and both of those candidates needed more than 10 years to be elected, time Rolen doesn’t have. The caveat is that he was competing for space on a pair of ballots so crowded that for the first time in history, back-to-back quartets of candidates were elected, with five other candidates topping 50% in 2018, and four others in ’19.

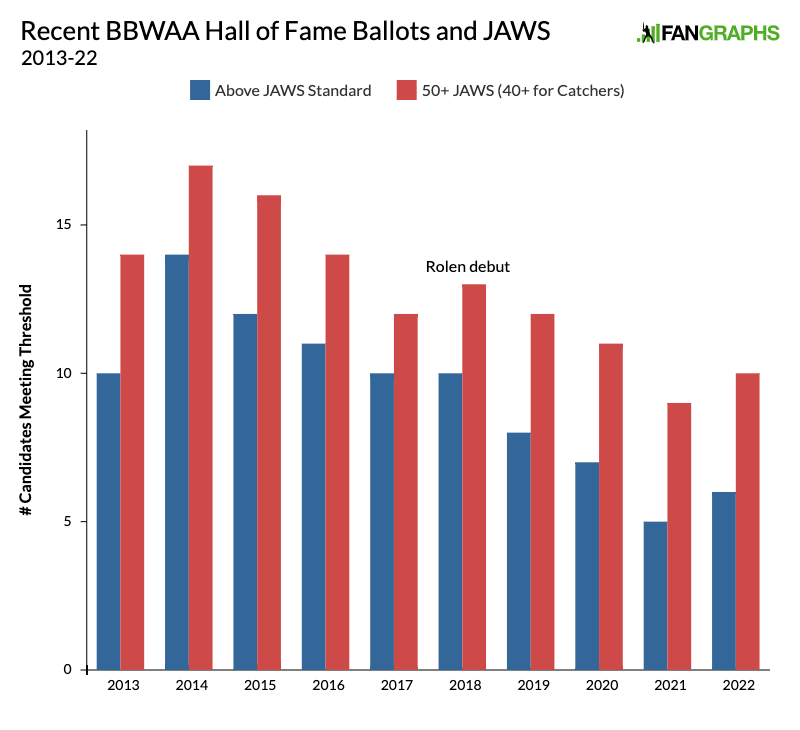

The trend of the ballot’s heavy traffic clearing is worth illustrating, and it’s applicable to several candidates who have lingered on the ballot, awaiting their opening:

Where Rolen was one of 10 candidates who met the JAWS standards at their positions when he debuted in 2018, and one of 13 with a JAWS of at least 50, he’s now one of six in the former group and 10 in the latter; the counts were five and nine last year, which left room for voters to consider adding candidates they’d previously bypassed.

One of my biggest fears heading into any election cycle is a strong candidate immediately suffering the indignity of falling off the ballot with less than 5% of the vote, cast into oblivion like Bobby Grich, Lou Whitaker, Kenny Lofton, Ted Simmons (the first player to rebound from such a fate by being elected by a small committee) and others. Players who derive a significant chunk of their value from on-base percentage and defense, but lack big triple crown stats, often suffer such a fate. Rolen fits that description to tee, though thankfully he survived those first two election cycles, and has since gained significant ground. Suddenly, he’s closer to the necessary 75% than he is to the 10.2% he debuted with.

Since the writers returned to voting annually in 1966, eight other candidates have landed in the 47% to 60% range in their fourth year on the ballot. That group includes two still-eligible candidates who haven’t been elected, namely Curt Schilling and Omar Vizquel, both of whom have accumulated significant non-baseball reasons for voters to hesitate to support them. The other six took an average of 4.2 years to gain entry, ranging from two for Mike Mussina, who received 51.8% in 2017, to six for Don Drysdale, who received 57.8% in 1978. Mussina and Jeff Bagwell (54.3% in 2014, elected three years later) are the only ones who hail from the period of candidates with 10 years of eligibility instead of 15, both lost five years in mid-candidacy with the Hall’s rule change in 2014. Both Bagwell and Mussina started with higher percentages than Rolen (41.7% for the former, 20.3% for the latter), but I think they illustrate how close Rolen is to election.

Could he get there this year? I don’t get the sense of a huge groundswell of support that would carry him over the threshold, but it’s early in the election cycle in terms of voters sending in their ballots. Ryan Thibodaux’s Ballot Tracker has received just nine thus far; Rolen has been on seven of them, picking up one new vote, but we’re still in small-sample territory.

To reach 75%, Rolen would need the sixth-largest year-to-year jump (22.13%) since 1967, squeezing in just ahead of Jim Rice (22.12%):

| Rk | Player | Yr0 | Pct0 | Yr1 | Pct1 | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luis Aparicio+ | 1982 | 41.9% | 1983 | 67.4% | 25.5% |

| 2 | Barry Larkin+ | 2011 | 62.1% | 2012 | 86.4% | 24.3% |

| 3 | Gil Hodges+ | 1969 | 24.1% | 1970 | 48.3% | 24.2% |

| 4 | Nellie Fox+ | 1975 | 21.0% | 1976 | 44.8% | 23.8% |

| 5 | Hal Newhouser+ | 1974 | 20.0% | 1975 | 42.8% | 22.8% |

| 6 | Jim Rice+ | 1999 | 29.4% | 2000 | 51.5% | 22.1% |

| 7 | Don Drysdale+ | 1976 | 29.4% | 1977 | 51.4% | 22.1% |

| 8 | Larry Walker+ | 2019 | 54.6% | 2020 | 76.6% | 22.0% |

| 9 | Vladimir Guerrero+ | 2017 | 71.7% | 2018 | 92.9% | 21.2% |

| 10 | Larry Walker+ | 2018 | 34.1% | 2019 | 54.6% | 20.5% |

| 11 | Johnny Sain | 1974 | 14.0% | 1975 | 34.0% | 20.0% |

| 12 | Early Wynn+ | 1970 | 46.7% | 1971 | 66.7% | 20.0% |

| 13 | Minnie Minoso+ | 1985 | 1.8% | 1986 | 20.9% | 19.1% |

| 14 | Phil Cavarretta | 1974 | 16.7% | 1975 | 35.6% | 18.9% |

| 15 | Early Wynn+ | 1969 | 27.9% | 1970 | 46.7% | 18.8% |

| 16 | Yogi Berra+ | 1971 | 67.2% | 1972 | 85.6% | 18.4% |

| 17 | Scott Rolen | 2019 | 17.2% | 2020 | 35.3% | 18.1% |

| 18 | Ralph Kiner+ | 1966 | 24.5% | 1967 | 42.5% | 18.0% |

| 19 | Scott Rolen | 2020 | 35.3% | 2021 | 52.9% | 17.6% |

| 20 | Billy Williams+ | 1982 | 23.4% | 1983 | 40.9% | 17.5% |

It’s worth noting that Rolen already has two of the 20 largest jumps of this period, and that voters have been malleable enough to produce five of those 20 jumps over the past four election cycles. Granted, all of those were smaller than the one he needs this year, and the sense of urgency that applied to Walker’s case doesn’t really apply to Rolen’s.

But there is this: Rolen represents the best chance for the voters to send a candidate untainted by major controversies to Cooperstown this year. The debates surrounding Schilling, Barry Bonds, and Clemens are likely to be rancorous and polarizing, and first-year candidate David Ortiz has two issues that could act as a drag on his candidacy, namely the DH factor and his reportedly positive test for PEDs during the 2003 survey testing. Sunday’s Era Committee elections of Jim Kaat and Oliva mean that the Hall will have living candidates to induct next summer, but both are 83 years old; the other four honorees are deceased, and one has been so for over a century (Bud Fowler, who died in 1913). Rolen would provide some youth to the proceedings.

Even if he doesn’t get in on the 2022 ballot, it does appear that Rolen is on his way to Cooperstown sooner rather than later. Three years ago, that seemed highly unlikely, but here we are.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

It boggles my mind how poorly the BBWAA (and committees, for that matter) treat third basemen.

Speaking of which, didn’t Santo also drop off due to the 5% rule?

Yeah, but I’d say that center fielders have it even worse, look at Lofton, Jones, and Edmonds.

One problem there, I think, is that center fielders don’t get enough credit for it being a more difficult defensive position (and for all the good ones being plus defenders, because otherwise they’d be moved to left or right). They get punished for not hitting as well as the best hitting left and right fielders.

Catchers, third basemen, and center fielders are the three underrepresented positions, and roughly in that order. You have to be an absolute monster at the plate like Wade Boggs or George Brett to get in as a third baseman. Center field is hard they have had some problems contextualizing defensive value in CF, which hurts guys like Edmonds / Lofton / Jones. Well, that and because guys like Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle are close to, if not the best position players in the history of the game. So the standard that voters compare them to are kind of silly.

You may have a point of CF defense being undervalued compared to the middle infield, but who claims that good defensive CFs should be moved to the corners?! RFs might have stronger arms, but otherwise CF is obviously the most skilled defensive position in the OF.

It’s the LFs who should generally be playing elsewhere in the outfield if they are truly elite defensemen (outside of rare situations like Starling Marte’s earliest years).

The comment you’re responding to agrees with you.

While the above commenter does seem to agree with me personally, he/she also says that some people think good defensive CFs should be moved to the corner outfield, whereas I’m saying nobody thinks that and that the opposite is more or less actually true.

“he/she also says that some people think good defensive CFs should be moved to the corner outfield, ”

No. I said that players who stay in CF tend to be plus defenders, because *otherwise* (meaning, if they were not) they would be moved to left or right. So average fielding CFs are better fielders than average for their position LFs or RFs, but the voters don’t act like they understand or value that.

I’m sorry that you completely misunderstood my statement.