JAWS and the 2023 Hall of Fame Ballot: Jered Weaver

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2023 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule, and a chance to fill out a Hall of Fame ballot for our crowdsourcing project, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball-Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

| Pitcher | Career WAR | Peak WAR Adj. | S-JAWS | W-L | SO | ERA | ERA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jered Weaver | 34.6 | 31.2 | 32.9 | 150-98 | 1,621 | 3.63 | 111 |

It’s not easy to follow in an older sibling’s footsteps, particularly when that older sibling is a first-round draft pick, a top prospect, and a bona fide major league starting pitcher. Yet given a leg up by the benefit of Jeff Weaver’s experience — not that the 6-foot-7, 210-pound righty needed it — Jered Weaver advanced beyond big brother’s accomplishments. In a 13-year career (2005–17), he made three All-Star teams and finished among the top five in the Cy Young voting three times, serving as a rotation stalwart on four Angels teams that made the playoffs. In 2012, he pitched a no-hitter, the 10th in franchise history.

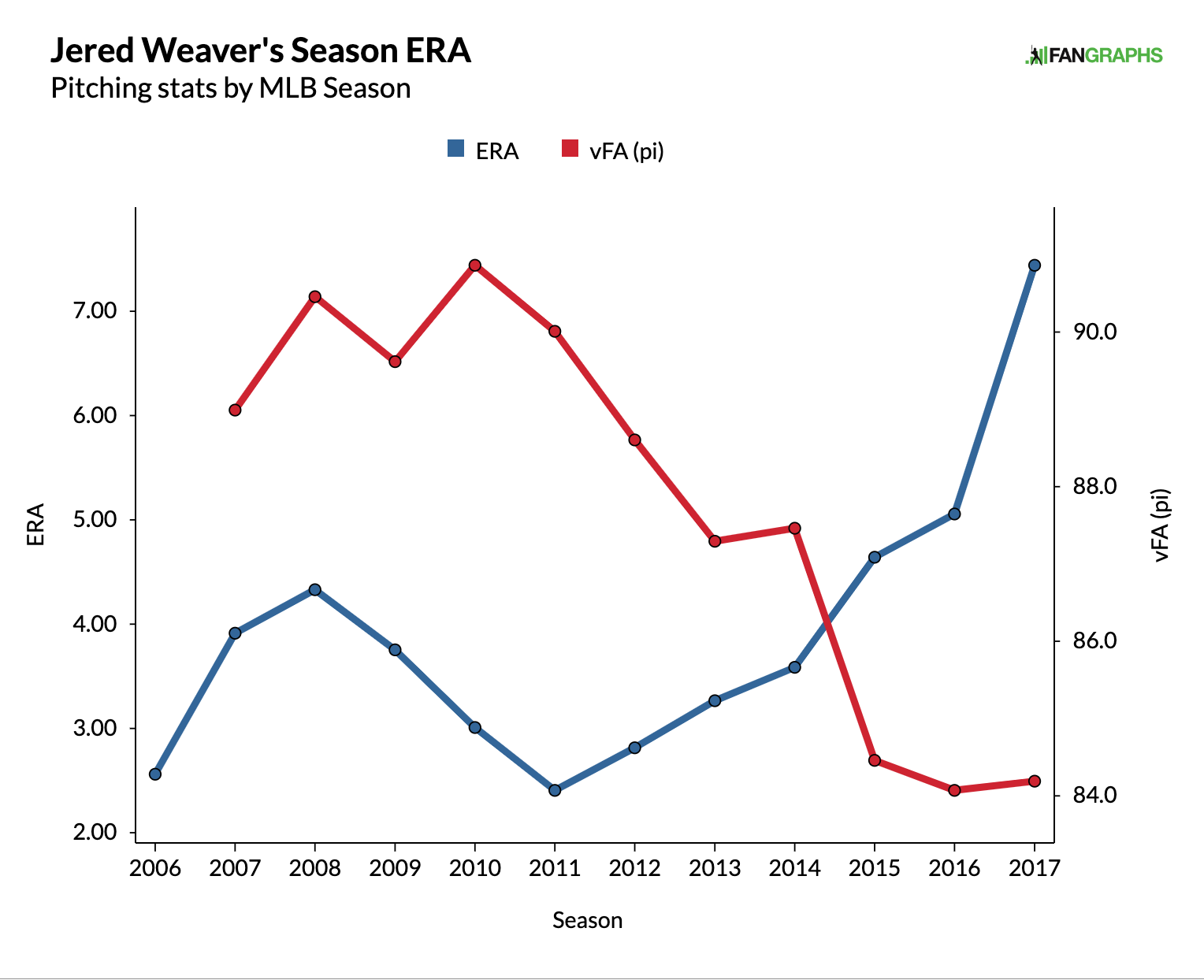

Despite his size, Weaver wasn’t dependent upon power. His violent, cross-body delivery produced deception, and his long limbs resulted in great extension, helping his arsenal — a four-seamer that was initially 91–93 mph, a sinker that was 86–90, and a curve, slider, and changeup — play up. Like fellow 2023 ballot newcomer Matt Cain, he didn’t strike out a ton of hitters, but he ranked among the game’s best at suppressing batting average on balls in play via weak contact that included a ton of pop-ups. Unfortunately, the stress of his delivery took his toll on his hips and shoulders, and once his velocity waned into the mid-80s, he was a sitting duck. He threw his last major league pitch more than four months before his 35th birthday.

Jered David Weaver was born on October 4, 1982 in Northridge, California and grew up in suburban Simi Valley, the younger of two sons of Dave and Gail Weaver. An electrical contractor by day, Dave coached both Jeff (b. 1976) and Jered in their youths; he would sit on a bucket outside of the dugout during their games, signaling pitches. “They were 8, 9, 10 years old, so the choices were limited to fastball or a not-so-fastball, which we now call a changeup,” wrote the Orange County Register’s Landon Hall in the wake of the younger Weaver’s no-hitter in 2012.

“I live and die every pitch Jered or Jeff make in my life,” Dave told Hall. “I still think I’m sitting on the bucket calling their pitches. For me, I’m probably a lot more nervous than Jered ever will be.”

Growing up, Jeff was the more workmanlike of the two brothers, digging ditches for his father’s company at 15 years old, not trying out for the varsity baseball team at Simi Valley High School until his senior year (he threw fewer than 30 innings), and making the Fresno State team as a walk-on. Jered was the prodigy for whom sports came much more easily. He starred in basketball and baseball in high school, earning All-League and first team All-Los Angeles Times honors in the latter before accepting a scholarship to Long Beach State. Along the way, he got his first exposure to the majors, spending weeks in the summers with Jeff after he reached the show with the Tigers in 1999. “He was able to hang around the clubhouse, shag some balls, get a little idea what this is all about,” said Jeff in 2009. The age gap between the two was too wide for them to be particularly close when they were under the same roof, but finally, the brothers bonded over their devotion to baseball.

Jered put together a stellar collegiate career, going 37–9 with a 2.43 ERA overall and 15–1 with a 1.62 ERA and 13.3 strikeouts per nine in 144 innings as a junior in 2004 and throwing 46 consecutive scoreless innings for Team USA’s college national team the summer before. His junior year performance earned him the Golden Spikes Award as the country’s top amateur baseball player; the Dick Howser Trophy as the national collegiate baseball player of the year; the Roger Clemens Award (now the National Pitcher of the Year Award in the wake of Clemens’ scandals); and the Baseball America College Player of the Year Award. He was the starting pitcher on Baseball America’s first-team All-American squad and the publication’s top draft prospect for 2004. Via BA, Weaver’s arsenal at the time consisted of “a 91–95-mph fastball, two variations of a nearly unhittable slider, an advanced feel for pitching, [and] excellent command and deception in his unconventional delivery.”

Signability concerns caused Weaver, a Scott Boras client, to drop in the draft as he sought a package similar to the five-year, $10.5 million major league deal of Mark Prior, the No. 2 pick in 2001. The Angels took Weaver with the 12th pick (two spots higher than his brother, who was taken by the Tigers in 1998). Negotiations took 51 weeks, right up to the final hour before the signing deadline; ultimately, he received a $4 million bonus, matching that of Prior, but without the major league portion of the deal.

Weaver split his first professional season between High-A Rancho Cucamonga and Double-A Arkansas, posting a 3.91 ERA and 11.3 strikeouts per nine in 76 innings and then capping that with a trip to the Arizona Fall League. He began the 2006 season at Triple-A Salt Lake while his brother began the year in the Angels’ rotation, having signed a one-year, $8.3 million free agent deal in February. “I didn’t really want to step on his toes,” Jeff told Sports Illustrated’s Richard Hoffer. Jered gave him the green light and dominated at Salt Lake to the tune of a 2.22 ERA and 10.9 strikeouts per nine over the course of 11 starts, a stint that was interrupted by his being called up when reigning AL Cy Young winner Bartolo Colon hit the injured list with shoulder inflammation. On May 27, Weaver debuted with seven shutout innings against the Orioles, allowing just three hits and one walk and striking out five. He made three more starts and was off to a 4–0 record and 1.37 ERA when the Angels sent him back to Salt Lake to accommodate Colon’s return.

That gave Jeff, who was on his way to being torched for a 6.29 ERA in 16 starts, a brief reprieve, but less than three weeks later, in what could have rated as the most awkward moment of the 400-plus brother acts in major league history (or the 100-ish brothers-as-teammates situations), the Angels designated Weaver the Elder for assignment to make room for Weaver the Younger. “When I saw how well he was pitching, and I was struggling to get into a groove, I knew it was a possibility,” Jeff told Hoffer. “It’s tough because you wanted to have it last and continue to have a chance to pitch with him, but at the same time it’s a business.”

Traded to St. Louis, Jeff continued to scuffle to the tune of a 5.15 ERA, but in October, Cardinals Devil Magic took over as he posted a 2.43 ERA and won three of five starts, capped by an eight-inning, one-run performance in the World Series-clinching Game 5 against the Tigers. As for Jered, he picked up where he left off, allowing just two runs over his next three turns and running his record to 9–0 with a 1.95 ERA. He finished 11–2 with a 2.56 mark in 123 innings, good for a team-high 4.7 WAR, but he placed a distant fifth in the AL Rookie of the year voting, with Justin Verlander winning.

It was an auspicious beginning, but given his underlying .238 BABIP and 3.90 FIP, Weaver couldn’t sustain that level. Settling into the middle of the rotation, he did help the Angels to three straight AL West titles from 2007 to ’09, averaging 30 starts, 183 innings, a 3.99 ERA (112 ERA+), 4.00 FIP, and 2.9 WAR. The last of those seasons was his best in that span, with a robust 5.8 runs per game of offensive support helping him to a 16–8 record to go with his 3.75 ERA (117 ERA+) and 3.5 WAR. That season featured an historic event: the two Weavers squaring off in Anaheim on June 20, becoming the eighth set of brothers to start against each other and just the third in the Wild Card Era:

| Brother 1 | Team | Brother 2 | Team | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jesse Barnes | BSN/BRO | Virgil Barnes | NYG | 5x, 6/26/1924–6/25/1926 |

| Joe Niekro | CHC/HOU | Phil Niekro | ATL | 9x, 7/4/1967–9/13/1982 |

| Gaylord Perry | CLE | Jim Perry | DET | 7/3/1973 |

| Pat Underwood | DET | Tom Underwood | TOR | 5/31/1979 |

| Greg Maddux | CHC/HOU | Mike Maddux | PHI | 2x, 9/29/1986–7/31/1988 |

| Pedro Martinez | MON | Ramon Martinez | LAD | 8/29/1996 |

| Alan Benes | CHC | Andy Benes | STL | 9/6/2002 |

| Jered Weaver | LAA | Jeff Weaver | LAD | 6/20/2009 |

Jeff, who had resurfaced with the Dodgers after spending all of 2008 in Triple-A, allowed two runs in five innings and got the win; Jered, who was roughed up for six runs and 10 hits in 5.1 innings, took the loss. The latter had carried a 2.08 ERA, 3.33 FIP, and a 48-inning homerless streak into the game but was hit for a 5.01 ERA and 4.58 FIP the rest of the way. Still, it was his best season since his rookie campaign.

The Angels didn’t make it out of the Division Series in 2007 or ’08 against the Red Sox; Weaver made a five-inning, two-run start in the former but was limited to two relief innings in the latter. In 2009, the Angels slayed the Boston dragon, with Weaver turning in a two-hit, one-run effort over 7.1 innings in Game 2 of the ALDS. After a five-inning, three-run start in Game 3 of the ALCS against the Yankees, he made two further appearances out of the bullpen, but the Bronx Bombers prevailed.

Thanks to an adjusted arsenal in 2010 (fewer changeups, more curves, and most importantly an improved sinker against which opponents batted .220), Weaver boosted his strikeout rate from 19.7% to 25.7%, leading the majors with 233 whiffs. He also upped his groundball rate from 30.9% to 36% and got his home run rate below 1.0 for the first time. His 3.01 ERA was his lowest since his rookie season and ranked fifth in the AL, as did his career-best 3.06 FIP; he also set highs with 224.1 innings (third) and 5.2 WAR (fourth). That kicked off a streak of three straight seasons in which he made the AL All-Star team and received Cy Young support, placing fifth in the voting in 2010. The Angels, though, took a step backwards, with seasons of 80, 86, and 89 wins, none of which were good enough to reach the postseason — the last of those even with the help of Mike Trout’s legendary performance as a rookie.

Weaver earned the All-Star Game start for the AL in 2011 on the strength of an 11–4, 1.96 ERA first half, throwing a scoreless inning highlighted by a strikeout of Carlos Beltrán. He placed second in the Cy Young voting (a distant second, as Verlander won unanimously) after finishing 18–8 with a 2.41 ERA and 6.9 WAR; those last two figures ranked second to Verlander, the ERA by a single point. Weaver became the rare Boras client to sign an extension without testing free agency — five years and $85 million, in his case — and went 20–5 with a 2.81 ERA in 2012, leading the league in wins despite missing three weeks due to lower back inflammation; his ERA placed third, his 4.3 WAR ninth. This time he finished third in the Cy Young voting, as David Price narrowly edged Verlander.

The highlight of that 2012 season was Weaver’s May 2 no-hitter against the Twins, the Angels’ second within a 10-month span, following Ervin Santana‘s no-hitter against Cleveland on July 27, 2011. Just two batters reached base: Chris Parmelee in the second inning after a passed ball on strike three, and Josh Willingham in the seventh via a walk. A charging, bare-handed pickup of a Jamey Carroll bunt by third baseman Mark Trumbo in the third inning and a running catch of Alexi Casilla’s fly ball by right fielder Torii Hunter for the final out both helped preserve the no-hitter.

Weaver had come close to a no-hitter before, or at least a combined one; on June 28, 2008 in Los Angeles, he threw six hitless innings against the Dodgers, who nonetheless scored an unearned run via two errors (one of them his own, on a Matt Kemp grounder), a stolen base, and a sacrifice fly. Jose Arredondo relieved him and threw two perfect innings, but as the Angels never scored, they didn’t get to pitch a ninth inning to make it an official no-hitter. Given the ugly line — three walks and a hit batsman to go with those errors — it was just as well.

Weaver’s 2013 season quickly hit a bump in the road. In his second start of the year, on April 7, he suffered a non-displaced radial head fracture in his left elbow, sidelining him for seven weeks. He pitched well upon returning, finishing with a 3.27 ERA and 3.7 WAR in 154.1 innings. It was all downhill from there, unfortunately, as his ERA would rise and his WAR fall in each of the next four seasons (a trend that had actually begun with 2012). Underlying it was a consistent decline in his fastball velocity, which was already comparatively meager to begin with; he last averaged 90 mph with his four-seamer in 2011.

Strong offensive support helped Weaver lead the AL in wins again in 2014, as he went 18–9, but his 3.59 ERA merely equated to a 100 ERA+. The Angels won 98 games and the AL West but were swept by the Royals in the Division Series, with Weaver’s seven-inning, two-run effort in Game 2 going for naught. The team hasn’t been back to the playoffs since, making this Trout’s only postseason appearance thus far.

Weaver’s 2015 (4.64 ERA, 0.5 WAR) and ’16 (5.06 ERA, -0.6 WAR, and a league-leading 37 homers allowed) were increasingly ugly, as his body just wouldn’t cooperate. “Hip, shoulder functionality… stuff wasn’t firing like I wanted to,” he told the Orange County Register’s Jeff Fletcher in 2018. “I was always throwing around some kind of nagging thing. I was on anti-inflammatories and trying to make it through every five days.” Though Weaver managed 31 starts in 2016, his fastball averaged just 83.8 mph. “There were scared times,” he told Fletcher. “I would have nightmares, before I pitched, of getting hit in the face and stuff. You try throwing a 3–1 fastball 83 mph to a power hitter. There were times I threw balls hoping they didn’t come back at me. You can’t pitch that way. It’s tough.”

Even in 2016, Weaver did have his moments, such as his three-hit shutout of the A’s on June 19 and a respectable 3.63 ERA (but a 4.78 FIP) over his final seven starts. Still, when his contract ended, the Angels didn’t so much as offer a minor league deal. Instead, Weaver signed a $3 million deal with the Padres, but even in sunny southern California, he was in for more rough sledding. He made nine starts, and while he managed a 3.91 ERA through his first four, his FIP never got below 6.51. The Padres lost all nine of his starts, and he allowed multiple homers in seven of them.

After the best of those turns — a six-inning, one-run effort against the White Sox on May 14 in Chicago — Weaver returned to Petco Park and retired just two of nine batters in a seven-run outing that raised his ERA to 7.44. Padres fans booed him off the mound, and the team placed him on the IL with hip inflammation (a phantom injury according to Weaver). On June 22, he made a rehab start for the Triple-A El Paso Chihuahuas. “The first pitch of the game, I looked back and saw 82 (mph, on the scoreboard) and my body, my heart and mind completely shut down,” Weaver told Fletcher. He allowed three runs in three innings, went back on the IL for another two months, then conceded it was time to retire. The timing was such that he’s one of five former Angels on this Hall of Fame ballot, along with John Lackey, Mike Napoli, Francisco Rodríguez, and Huston Street.

Looking back at his body of work, statistcally Weaver had a lot in common with Cain despite a fastball that was about four clicks slower. Both had strikeout rates just 3% above the league average (103 K%+), with Weaver better at preventing walks (79 BB%+ to Cain’s 97) and Cain better at preventing homers (92 HR%+ to 108), though it should be pointed out that park adjustments aren’t yet built into our plus stats, and AT&T Park was even more homer-suppressing than Angels Stadium. Among pitchers with at least 2,000 innings since 2005 (the year Cain debuted, with Weaver following just months later), they rank first and second for the highest normalized fly ball rate (Weaver 130 FB%+, Cain 119) and lowest normalized groundball rate (Weaver 75 GB%+, Cain 85).

Weaver owns the Wild Card Era’s highest infield fly ball rate among pitchers with at least 2,000 innings (13%), with Cain fourth (12.2%); meanwhile, Weaver is third in home runs per fly ball (8.9%) and Cain first (8.2%). The pair are just behind Clayton Kershaw for the lowest BABIP of the Wild Card Era:

| Pitcher | Team | IP | BABIP | ERA | FIP | E-F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayton Kershaw | 2008-2022 | 2581.0 | .270 | 2.48 | 2.76 | -0.28 |

| Matt Cain | 2005-2017 | 2085.2 | .272 | 3.68 | 3.92 | -0.24 |

| Jered Weaver | 2006-2017 | 2067.1 | .273 | 3.63 | 4.07 | -0.44 |

| Tim Wakefield | 1995-2011 | 3006.0 | .273 | 4.43 | 4.74 | -0.31 |

| Barry Zito | 2000-2015 | 2576.2 | .274 | 4.04 | 4.39 | -0.35 |

| Johan Santana | 2000-2012 | 2025.2 | .276 | 3.20 | 3.44 | -0.24 |

| Woody Williams | 1995-2007 | 2120.0 | .276 | 4.20 | 4.66 | -0.46 |

| Jamie Moyer | 1995-2012 | 3073.0 | .278 | 4.20 | 4.53 | -0.33 |

| Justin Verlander | 2005-2022 | 3163.0 | .278 | 3.24 | 3.36 | -0.12 |

| Pedro Martinez | 1995-2009 | 2567.2 | .279 | 2.91 | 2.89 | 0.02 |

| Al Leiter | 1995-2005 | 2052.0 | .281 | 3.64 | 4.09 | -0.45 |

| Tom Glavine | 1995-2008 | 2891.0 | .281 | 3.51 | 4.13 | -0.62 |

| R.A. Dickey | 2001-2017 | 2073.2 | .281 | 4.04 | 4.41 | -0.37 |

| Tim Hudson | 1999-2015 | 3126.2 | .281 | 3.49 | 3.78 | -0.29 |

| Bronson Arroyo | 2000-2017 | 2435.2 | .282 | 4.28 | 4.60 | -0.32 |

| Ervin Santana | 2005-2021 | 2486.2 | .282 | 4.11 | 4.31 | -0.20 |

Cain was the more successful of the two in terms of championships and earnings (he signed a six-year, $127.5 million extension in 2012), but Weaver received more recognition in the Cy Young voting and has the edge both in traditional won-loss records (he’s 52 games over .500 thanks to good offensive support, Cain 14 games under at 104–118 due to spotty support) and in WAR (34.6 to 29.1). Many of their other career numbers are similar, and while it may be an overstatement to say the statistical resemblance is uncanny, at a time when the game has swung increasingly toward power pitching, both are reminders that there’s more than one route to success from a major league mound.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

The methodology that says Andy Pettitte and Tim Hudson were a similar level to Tom Glavine tells us that Ricky Nolasco was roughly as effective as Cain and Weaver.

ANYWAY – Weaver was such a good pitcher…and always a dreaded matchup.