Jordan Montgomery and the Sinker Renaissance

Jordan Montgomery hasn’t had the easiest of careers. While he established a name for himself with a solid rookie campaign in 2017, extended battles with injuries kept him off the mound in subsequent years. An underwhelming return in 2020 (5.11 ERA) raised questions about his future with the Yankees. But the much better peripherals (3.87 FIP, 3.65 xFIP) signaled a return to form, and the following year, Montgomery put together somewhat of a second breakout season, anchoring a rotation that was considerably more volatile than it is now.

Last year, Montgomery made an adjustment I thought was interesting but never got to write about, drastically raising his four-seam fastball usage in September, which had its pros and cons. On one hand, this newfound reliance on the hard stuff granted Montgomery the highest monthly strikeout rate of his career, as hitters found themselves whiffing at elevated fastballs. On the other hand, it led to a barrage of hard contact; the shape of Montgomery’s fastball isn’t great to begin with, and the corresponding decrease in sinker usage didn’t help, either.

Considering Montgomery’s excellent command, though, I believed he could make this new approach work in the long-term. So naturally, the development we’ve seen this season is… a near-abandonment of the four-seamer! His last five starts all featured a four-seam fastball usage under 10%; against the Tigers on June 5, Pitch Info thought he didn’t throw a single one. But Montgomery isn’t just tinkering with his pitch mix. Check out this side-by-side view of his typical arm slot in 2021 (left) versus 2022 (right):

It’s subtle, but you can see that Montgomery is throwing slightly less over-the-top than before. The Hawk-Eye readings bear this out: he’s lowered his average vertical release point from 6.70 feet to 6.47. What good is a different angle for? My theory is that it’s helped Montgomery exchange vertical movement for horizontal. His sinker is getting more drop and arm-side run than ever before, which is the sort of trade-off stuff models absolutely love (and opposing batters hate). It’s come at the cost of a worse four-seamer, but realistically, improving two diametrically opposed fastballs is a tall order. Montgomery made a choice to stick with one, and so far, it’s worked wonders.

Originally, this article had a much bigger focus on Montgomery. But looking around the league, I couldn’t help but notice several other pitchers who’ve placed a recent emphasis on their sinkers. There are the obvious names, like Clay Holmes and his triple-digit, bowling-ball sinkers, or basically the entire Giants rotation sans Carlos Rodón. Lesser-known examples (to the average fan, at least) include Mitch Keller, who, as noted by Michael Ajeto, switched to a sinker-slider combo after a disappointing start to his season. Oh, and did you know Robbie Ray reintroduced his long-dormant sinker? Wild. Maybe he reckons it’ll help curb the home runs.

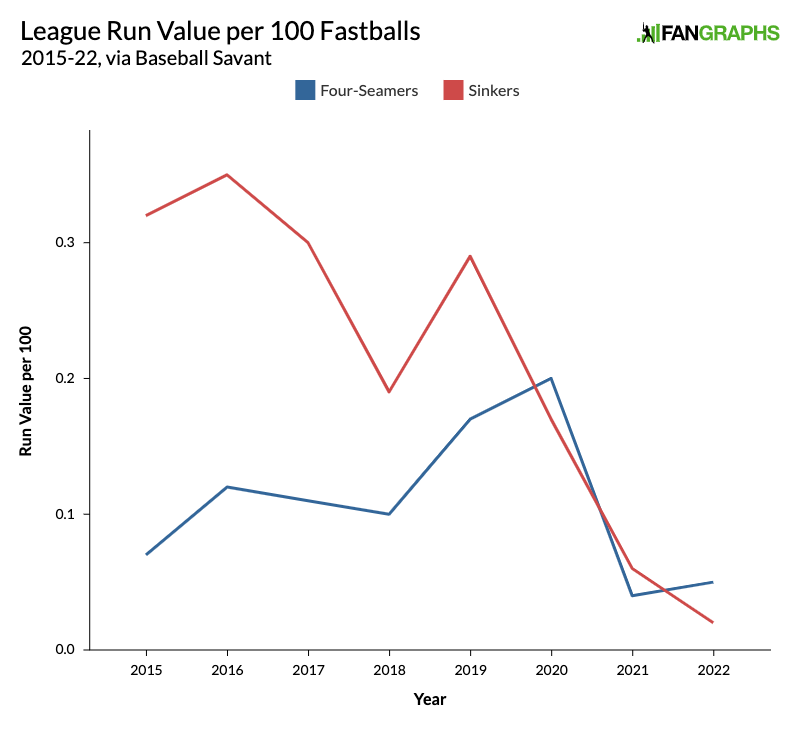

An oft-cited reason for why teams encouraged their pitches to abandon the sinker in favor of the four-seamer is that the latter pitch induces way more swings-and-misses, especially when located up. But it’s also crucial to consider that, in general, sinkers are inferior to four-seamers. As our own Ben Clemens concluded in 2019, when you factor in both contact rate and quality, the average four-seamer carries an edge over the average sinker. Right. Well, about that:

As straightforward as it is, run value isn’t a perfect metric; it’s dependent on context, meaning a pitcher can inflate the run value of a pitch by using it exclusively in high-leverage spots. But because we’re measuring the league as a whole, we can assume any bias has been washed out. So what does run value tell us? Over the past few years, sinkers have rapidly become effective; so far this season, they’re even outpacing four-seamers. Consider the massive gap between the two pitches back in, say, 2015, and how it’s essentially disappeared. We can throw that truism from earlier out the window. It’s pretty fascinating.

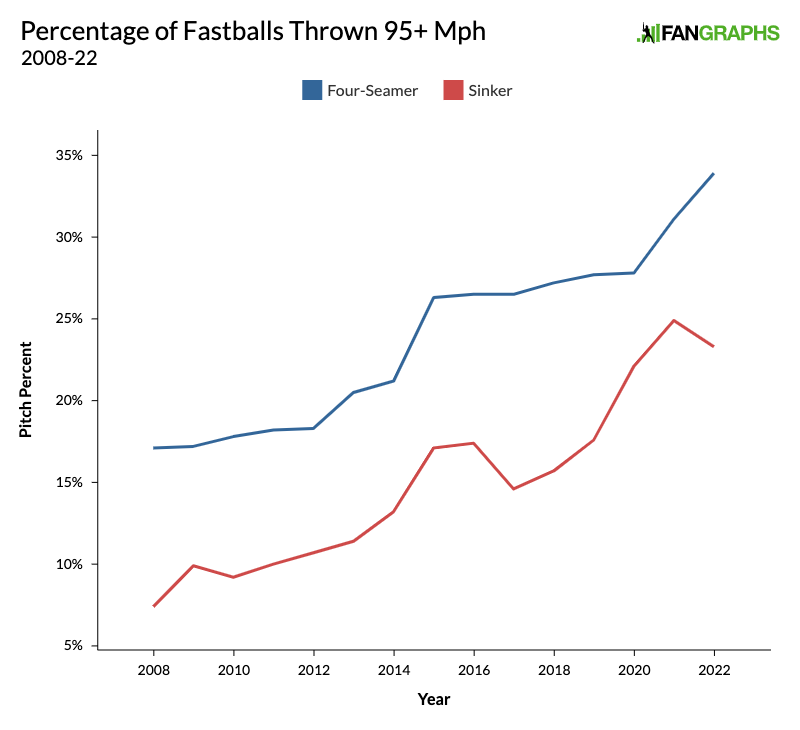

A logical explanation is that the league has been gradually weeding out sinkers of dubious quality. All those pitchers who made the switch to a riding four-seamer did so by dropping their poor sinkers; it’s probably no coincidence that this season represents another all-time low in sinker usage (15.4%). But we shouldn’t ignore the numerous pitchers who have abandoned their lackluster four-seamers in favor of sinkers. The average sinker isn’t just better because the bad ones are gone; there’s been an uptick in stuff, too. We can see this development in the percentage of four-seamers and sinkers thrown 95 mph or harder:

While four-seam velocity stagnated between 2015 and 2020, sinker velocity was busy catching up. And though the gap has widened this season, think about the overall progress sinkers have made in the past decade and a half. The percentage of four-seamers at 95 mph and up has doubled since 2008; for sinkers, it’s nearly quadrupled, with a majority of that gain occurring in recent years. Leave it to Aaron Judge to summarize the ascent of these so-called turbo sinkers:

“Before, the sinker used to be guys throwing 90, 91 mph, and now you’ve got guys throwing 100… I didn’t know I was going to get attacked like that.”

In Judge’s past, the typical sinkerballer looked a lot like Marco Gonzales. He’s still around today, but there’s more diversity within the clan. Brusdar Graterol, who achieves triple digits with unbelievable ease, relies on a sinker. Sean Hjelle, whose towering height might make you think he lives at the top of the zone, actually thrives on the back of his sinker, which has allowed a measly .173 wOBA thus far. If you thought sinkers only belonged in the repertoires of old-school, pitch-to-contact hurlers, think again.

It’s not just the velocity, either. Speed matters, but so does movement, and it’s hard to wield a plus sinker without enough drop and arm-side run to avoid the barrel of the bat. Are pitchers also seeing gains on their sinker movement? For a while, the answer was no. But if there’s anything we should know by now, it’s that preconceived notions of what is and isn’t possible are meant to be shattered:

| Year | Vmov (in.) | Hmov (in.) |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 9.3 | 14.6 |

| 2021 | 9.3 | 14.8 |

| 2022 | 8.8 | 15.0 |

This is amazing. A change of this magnitude says a lot about the evolution of one pitch. Compared to last season, the entire league has shaved half of an inch of vertical movement off its sinker, which is helpful for a pitch that generally needs to, well, sink. It almost makes me think there’s been a calibration error of some kind. But if that were true, we’d expect four-seam fastball movement to be down as well, only that hasn’t been the case. Instead, four-seamers are averaging more ride than ever. So maybe the new baseball is aiding pitchers in generating movement. Perhaps teams really have unlocked the secret to throwing a great sinker. Whatever the reason, the representative sinker is improving on not just one, but two fronts. Gradually, that run value graph from earlier is starting to make sense.

Lastly, the sinker is getting a little help from its new friend. Look, I know it’s been talked to death already, but I have to bring up the sweeper. It’s just that important in helping us understand why sinkers are doing so well. For example: Take a sinker and a sweeper, compare the axes on which they spin, and you’ll find that the two pitches mirror each other. They’ll look the same out of a pitcher’s hand but break in opposite directions — the perfect recipe for deception, in other words. And since pitchers who average a low spin efficiency on their four-seamers are inclined toward the seam orientation necessary for a sweeper, it makes sense to convert them into sinkerballers instead. That’s what the Dodgers worked on with Yency Almonte, who now wields one of baseball’s best sinker-slider tandems. The sinker renaissance doesn’t happen without baseball’s trendiest breaking ball.

In an alternate universe where Montgomery remains healthy in 2018 and ‘19, it’s possible he elects to rely on his four-seamer. It’s when we lacked our current understanding of sinkers, after all. But in real life, he resurfaced at a time when we learned that if used properly, the sinker can be a better option than the four-seamer. You could argue Montgomery should return to his old fastball blend; indeed, the whiffs are down this season, in part because his current repertoire is tailored toward inducing soft contact. The point, however, is that sinkers are experiencing a revival, years after they were deemed extinct. Along with teammates as well as rival pitchers, Montgomery is one of many trailblazers in this era of pitching.

Statistics in this article are through games of June 16.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

I learned a lot from reading this article. This kind of quotidian breakdown of pitching trends is one of my favorite types of articles here. Keep up the good work.