Maikel Franco and Orioles Finally Find Each Other

It’s the third week of spring training games, and the Orioles have added a new starting third baseman who’s been available since December: Maikel Franco, seven-year big league veteran with Philadelphia and Kansas City. Baltimore’s roster construction has hardly changed in that time, and I doubt Franco and his career 1.03 WAR/600 needed to be humbled out of demanding a hefty multi-year contract. Both parties have known their situations for months, but are only just now finding each other. This is an odd transaction. Let’s try to unpack it.

Maikel Franco: $800K salary, $200K incentives, bonus if traded, parties agree that option can be utilized first few weeks due to late start, MLB deal. #orioles

— Jon Heyman (@JonHeyman) March 16, 2021

It isn’t as though the deal doesn’t make sense. Baltimore’s incumbent at the hot corner is Rio Ruiz, who has gotten a majority of the team’s starts at third base since the O’s claimed him off waivers before the 2019 season and who’s showed some modest fence-clearing ability, hitting 21 homers in 617 plate appearances. But his overall offensive profile is mediocre: His 90 wRC+ in 2020 stands as his career best. At 26, he’s exhausted much of the faith people had in him as a prospect, and his Statcast data doesn’t suggest there’s anything exciting hidden under the surface numbers. Ruiz’s value might top out at less than one WAR, and he entered camp running virtually unopposed for the starting job.

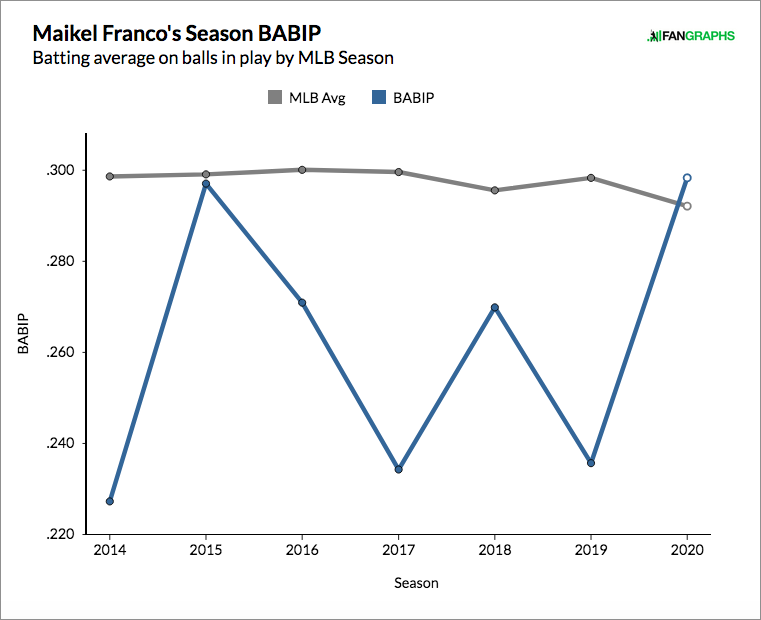

Enter Franco, who signed a change-of-scenery deal with the Royals in 2020 after a disappointing tenure in Philadelphia and turned in his best season in years, hitting .278/.321/.457 with eight homers, a 106 wRC+ and 1.3 WAR. That value placed him ninth among all third basemen, just ahead of peers like Eugenio Suárez and Brian Anderson. The bump in Franco’s production didn’t come from some random explosion in power numbers or a big jump in walk rate, though. He just finally got a normal distribution of balls in play to land for hits.

For years, Franco has faced an uphill battle in salvaging his offensive value because of BABIP figures well below .300. That hurt him even more than it would the average hitter, since so much of his value is in his ability to make lots of contact. When Franco is on, he can display 22–25-homer power and pepper the outfield with lots of hits while striking out only about 15% of the time. When those balls aren’t finding the grass, though, he doesn’t have the raw power or the plate discipline to sustain himself until better luck rolls around.

Where he managed to finally find those extra hits last year is difficult to say. A higher number of line drives would help, but per our numbers, Franco’s line drive rate only went from 16.6% in 2019 to 18% in 2020. Statcast claimed his line drive rate improved from 20.2% to 30.2%, and that likely comes to down to differences in the two measurements’ respective qualifications of liners and flies; that blurry area might be where he had some success. But it’s hard to see how that success is sustainable. Franco’s 2020 featured his lowest average exit velocity of the Statcast era, his lowest contact rate since 2014, and a .304 xwOBA that is right in line with how he’d performed over his previous three seasons. There are only so many ways to thrive offensively without walking much or hitting the ball hard.

And yet the Orioles still have good reason to target him. Franco is only 28, and he still has some name recognition around the league. If he starts this season off hot again, teams are going to take notice and could be willing to send Baltimore a low-level prospect or three in exchange for his services. Franco’s camp clearly knows that this is the ideal endgame from the Orioles’ perspective, which is why he’ll get a bonus if they deal him during the season. If he’s below replacement level again, the cost to the team in negligible.

It’s a straightforward enough signing, but one that serves as a reminder of how odd the offseasons of terrible teams can be. Contenders use the winter to address holes in their roster, sometimes with expensive moves and sometimes with cheap ones. There are bidding wars and waits for certain dominos to fall and all kinds of other things a team that wants to win must navigate.

But the Orioles don’t have the intention of winning games in 2021, and neither do several other teams across baseball. The all-in-or-all-out mentality of front offices incentivizes teams that aren’t going to be in contention not to spend to improve the team. Minimizing payroll keeps as much money in the owners’ pockets as possible, allows for precious roster spots to be used on young players to whom teams are committed to developing, and maximizes the value of the team’s future draft picks. It’s not hard to see why such a strategy has gained popularity.

Yet virtually no team goes an entire offseason without signing somebody. This winter, the Rockies stand as the only team who have not signed a big league free agent. Last year, there were no such teams. Despite bleak short-term outlooks, the Rangers signed six major league free agents this winter, the Tigers five, the Mariners four, the Diamondbacks three, and the Pirates two. And the Orioles now have two as well, with Franco and Freddy Galvis combining to form a brand new left side of the infield.

Why? What made Cedric Mullins an acceptable enough starting center fielder for Baltimore to keep him instead of signing a cheap veteran like Michael A. Taylor, Albert Almora Jr. or Jake Marisnick, but made Ruiz a poor enough option at third base to go and get Franco? And why did his deal take this long to happen, without injuries or any other visible factor changing the Orioles’ infield situation?

Perhaps the team’s timeline for Rylan Bannon has gotten less aggressive. Maybe the O’s just forgot Franco was out there, or the doldrums of spring training got to them enough that they wanted to spice things up by making a move they wouldn’t have made three weeks ago. It’s always strange to watch bad teams decide which holes to fix and which ones to let fester. But you always hope they’ll lean toward the former, and in turn give a player like Franco a job he’s earned.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

I think it’s more of a case of teams waiting until as late as possible, in order to obtain better deals. He would likely have got more than $800k had he signed a couple of months ago.