Max Scherzer Tests the Limits of the New Pitch Clock Rules

Pitchers, hitters, and the rest of us have spent the first couple weeks of this exhibition season adapting to the new pitch clock, but few players have set out to test the boundaries of the rule the way that Max Scherzer has. The future Hall of Famer’s search for an advantage has called to mind the philosophy offered by a hurler he’ll eventually join in Cooperstown, Warren Spahn: “Hitting is timing. Pitching is upsetting timing.” And the 38-year-old righty’s first two starts of the spring have demonstrated some ways in which a pitcher might weaponize the clock — and how such efforts might backfire.

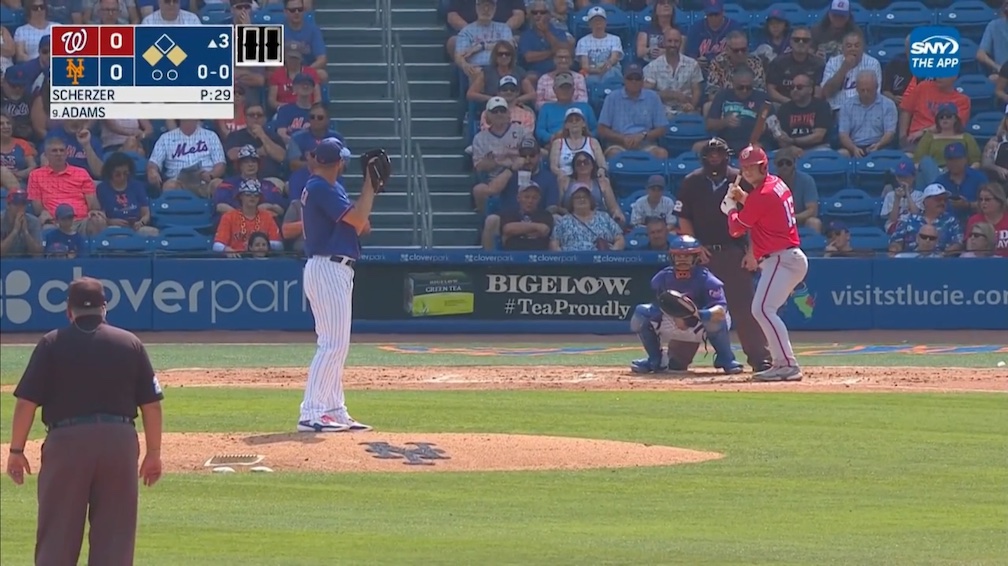

Scherzer made his Grapefruit League debut on February 26 at the Mets’ Port St. Lucie Clover Park against the Nationals, throwing two innings and striking out five while allowing three hits and one run. At the outset of the SNY broadcast, Mets play-by-play announcer Gary Cohen foreshadowed the three-time Cy Young winner’s clock-testing efforts by telling viewers, “I think he’d going to love this pitch clock more than anybody else in baseball because he is fully capable of going old school on you, gettin’ it and throwing it.”

While fully capable of pulling the occasional fast one, Scherzer doesn’t particularly stand out in that regard according to Statcast’s new-ish Pitch Tempo metrics, which measure the median time between pitches that follow a take (called strike or ball). Last season, Scherzer averaged 16.6 seconds between such pitches with nobody on base, 1.5 seconds faster than the major league average but a full four seconds slower than major league leader Brent Suter’s 12.6 seconds, and 2.5 seconds slower than Cole Irvin, the fastest pitcher in this context among those who made at least 20 starts last year. Within that latter group, Scherzer ranked 54th-fastest out of 135.

It’s important to note that Statcast’s pitch tempo figure isn’t directly comparable to the times being measured for the new rules, which require a pitcher to begin his delivery 15 seconds after receiving the ball from the catcher with nobody on base. The pitcher has 20 seconds to do so with a man on, and 30 seconds to do so when facing a new batter. Meanwhile, the batter must be in the box and ready to hit with eight seconds left on the clock, and can call for a timeout and step out of the box once per plate appearance. A pitcher can disengage (make a pickoff throw or step off the rubber) twice per PA. Pitchers who violate the timer are charged with an automatic ball, while batters who do so are charged with an automatic strike.

Statcast helpfully converts the pitch tempo numbers to timer equivalent numbers by subtracting six seconds, so Scherzer’s 16.6-second average with the bases empty translates to a timer equivalent of 10.6 seconds. In other words, with nobody on, he’s generally got plenty of leeway as far as the pitch clock goes. His 24.1-second pitch tempo average with men on base — a timer equivalent of 18.1 seconds — is a bit more plodding, ranking 87th among those 135 starters.

In that first start of the spring, Scherzer established a brisk pace against leadoff hitter CJ Abrams, whom he struck out on a 93-mph fastball. He then let the 30-second clock run all the way down to four seconds before starting to deliver his first pitch Luis Garcia, who eventually flew out. He followed that by striking out Joey Meneses on three pitches that took just 27 seconds, barely enough time for the Mets booth to tell viewers about Meneses’ amazing late-season call-up as a 30-year-old rookie who’d never been to a major league camp before:

Max Scherzer is an absolute psychopath and used the pitch clock to his advantage, striking out Joey Meneses in 27 SECONDS ? pic.twitter.com/QHvqk0WYFT

— The Game Day MLB (@TheGameDayMLB) February 27, 2023

Whew. For as impressive as that 27-second strikeout was, it’s worth noting that the Yankees’ Wandy Peralta dispatched the Pirates’ Tucupita Marcano in 20 seconds last Thursday:

Peralta could have struck out Marcano and still made it across a busy New York City intersection before the “Don’t Walk” sign started flashing, but I digress…

In the second inning of Scherzer’s first outing, after surrendering a leadoff single to Matt Adams, Scherzer held the ball until the clock ran down to four seconds before Michael Chavis called for his timeout. “Now he can make him really wait,” said Ron Darling in the booth. Indeed, Scherzer held his next pitch for 14 seconds before delivering, though Chavis countered by sneaking a 59.8-mph dribbler through the right side for a single that allowed Adams to lumber from first to third. Adams came around to score when center fielder Tommy Pham was unsuccessful in diving for Alex Call’s fly ball deep in the right-center field gap; a bad read by Chavis prevented a second run from scoring.

By that point, Scherzer had matched his first-inning total of 15 pitches but failed to retire any of the three hitters he faced. Relying on high heat and often running the pitch clock down to a few seconds, he recovered to strike out Travis Blankenhorn, Derek Hill, and Israel Pineda in order, ending his afternoon after 43 pitches.

After the outing, Scherzer gushed about the advantages of the new rule, telling reporters, “Really, the power the pitcher has now — I can totally dictate pace. The rule change of the hitter having only one timeout changes the complete dynamic of the hitter-and-pitcher dynamic. Yeah, I love it.”

More, via the Associated Press:

“I can work extremely quick. And I can work extremely slow,” Scherzer said. “There’s another layer here to be able to mess with the hitter’s timing.

“I can come set even before the hitter’s in the box. I can’t pitch until eight (seconds left on the clock). But as soon as his eyes are up, I can go. If his eyes are up with 12 seconds to go, I can fire.

“I had the conversation with the umpire (David Rackley) to make sure that’s legal. And that is (legal). I’m just getting used to how this is going to be in 2023.”

Scherzer wasn’t bothered by his lack of perfection, saying, “You are not going to be perfect out there, so it’s actually good to pitch in traffic now, work with [catcher] Omar [Narváez] now using the PitchCom, what we want to do and how the pitch clock was going to play today and be in that situation and use it. You go through all the different situations of what can be good and bad.”

Scherzer was referring to the fact that this season, pitchers are allowed to use PitchCom transmitters on the wrists of their glove hands. Last year, pitchers only had receivers, with catchers the only ones outfitted with transmitters; that required pitchers to shake off catchers until the two could agree on a pitch. Now Scherzer and other pitchers can call their own games, though Scherzer isn’t expected to rely upon it. After his second outing, during which he worked with catcher Tomás Nido, he told reporters, “I’m letting Nido call the game, it’s just when I want to throw a certain pitch in a certain situation… And it works. You could tell they were ready for me to work quickly today. You can use that to your advantage in speeding up and slowing down the game.”

Scherzer continued to test the boundaries of the rules in that second outing on March 3, again facing the Nationals at Port St. Lucie. Things went smoothly for the first two innings, during which he retired six straight hitters on a total of 21 pitches. After Ildemaro Vargas slapped an infield single to start the third, Scherzer upped his experimentation. Facing Victor Robles, he waited until two seconds were left on the clock to throw an 0-1 fastball, which Robles swung through, then tried to follow up with a quick pitch. Robles stepped out for his timeout, and as soon as he stepped back in, Scherzer tried to quick-pitch him again, but home plate umpire Jeremy Riggs called him for a balk:

Max Scherzer is called for a balk after attempting to quick-pitch Victor Robles. pic.twitter.com/RCmluX2h8K

— SNY (@SNYtv) March 3, 2023

On the broadcast, Darling pointed out that Robles wasn’t looking up when Scherzer began his delivery, which is why Riggs called the balk. Scherzer, however, believed that Riggs had signaled him to restart play.

“To me, the umpire had time, then he made a gesture or a signal like ‘you can go,’ and I go, Robles’ eyes are up, and I get called for a quick pitch balk,” Scherzer said afterwards. “He calls time, I come set, I get the green light, his eyes are up I’m going throw the ball. I thought that was a clean pitch. (The umpire) said no.”

The balk sent Vargas to second base, after which shortstop Luis Guillorme bobbled Robles’ grounder for an error. On the next pitch, Riley Adams hit into an apparent 5-4-3 double play, but Riggs ruled that Scherzer didn’t throw the pitch in time — he hadn’t lifted his leg by the point that the clock showed :00 — negating the outcome. On the broadcast, Cohen pointed out that had Adams collected a hit, the Nationals could have accepted the outcome of the pitch.

After Robles stole second, Scherzer followed with a well-executed version of what we might call “The Chavis Maneuver” based on his previous start: holding the ball until Adams took his timeout at the seven-second mark, then re-setting himself and pitching as soon as the hitter got both feet back in the box.

Max Scherzer, Pitch Clock Gamesmanship.

Long hold. Adams takes his only time out.

Then Max stays set so he can pitch as soon as Adams is ready. pic.twitter.com/3uj9ucDFEl

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) March 3, 2023

That was just the first out of the inning. Abrams grounded into a first-to-pitcher play where Pete Alonso knocked down the ball and recovered in time to get the batter, but Robles advanced. Call singled to left field, bringing him home. Garcia followed with a 393-foot homer to right field, then Guillorme made another error on a bad hop. After Jeimer Candelario doubled into the gap to bring home a run and Stone Garrett hit an infield single, manager Buck Showalter had to go get his co-ace, who had thrown a total of 50 pitches, 29 in the inning. Reliever David Griffin would allow both inherited runners to score, but all seven runs were unearned.

Not that spring ERAs matter one whit, of course. Scherzer didn’t seem perturbed about the rally or the sloppiness behind him, instead focusing on his tinkering. Via WFAN, he said, “You have to press the limit on what you can and can’t do to find out where the boundary is on this, and I pressed it today… We’re all working through this; hitters, umpires, pitchers. We have to figure out where the limit is.”

Scherzer is hardly alone in his search for the limits, or in having them backfire. That’s what spring is for, and everybody still has nearly four weeks to adapt. As The Athletic’s Marc Carig wrote on Twitter last week, “It is good that these rules mistakes are happening now in the fake baseball games and not the real baseball games. Adjusting to the rules is a great use of fake baseball.”

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

A lot of the stuff Scherzer is doing isn’t really anything that the pitch clock specifically is enabling – there was nothing in seasons past (unless I’m missing something here) to prevent a pitcher from holding the ball until a hitter steps out and then quick-pitching as soon as he’s back in, or pitching quickly in general, or pitching slower than expected, etc. I’d imagine that mixing up tempos is probably an advantage to the pitcher, but that would be true with or without a pitch clock… I’d guess we’ll see *slightly* more of this kind of thing this season just because of the focus on tempo the pitch clock brings, but if it brought that great of an advantage to the pitcher then surely things like the “Chavis Maneuver” would be common practice by now. Ultimately I think the biggest impact the pitch clock will have on the baseball we see will be its primary intended purpose – cutting down on the amount of dead time between pitches.

Seems like Scherzer sees a psychological advantage from forcing the hitter to burn his only timeout. I can see how it would make a difference in that after the timeout has been taken, there’s no longer the give-and-take delay that we’ve all become used to over the years; it felt virtually automatic that if the pitcher held the ball for a noticeable period of time, the batter would step out on him. Now the batter can only do that once per PA.

Agreed, that’s definitely the one major thing that *is* directly affected by the pitch clock. Even there though, I’m guessing the % of PAs in which a batter stepped out of the box more than once was extremely low, so that aspect probably won’t be all that much different than before either.

Watching this gamesmanship in spring training, my main question is how well this trick will work once hitters know he’s trying to get them to burn their one time-out and stop responding. So far (at least in his most obvious experiments) he’s been relying on what I think is effectively muscle memory or force of habit from past seasons, holding the ball and waiting them out. At some point batters have to respond strategically by just not asking for time, and I don’t know what his move is from there except to vary his pace more unpredictably.

This is the big thing. I get he’s trying to see what he can get away with here, but he’s also advertising his tactics for all to see. Once teams are a month into the season and see how pitchers will try to use the clock to their advantage it won’t be as effective, especially when batters have as much of an effect on the clock by waiting until 8 seconds to get in the box.

Unless his goal is to get the hitter thinking about the clock, and not the pitch…

While this is true, the pitcher is now expected to begin their wind up at a certain point as well. So it’s not like batters will be waiting more than 7-12 seconds at most unless the pitcher wants to give up a ball.

Well, in the past a batter could take his time getting back in the box after calling timeout (or even call another timeout) to where quick pitching in that situation isn’t possible. Now the batter has to be ready and alert within 7 or 12 seconds after calling a timeout. Even outside of timeouts, he usually only has 7 or 12 seconds to be ready and only as many as 22 seconds while also taking the time to walk to the plate.